The fashion industry has long attempted to bring the latest trends to the consumer. The fast-fashion trend seeks to

deliver this on a mass-produced scale to maximize profits and reduce costs.

In a world now dominated by fast fashion—where new collections are introduced constantly—a movement centering on environmental and economic responsibility is unfolding.

“Cotton is water intensive, and it doesn’t stop at the growing of it, but the harvesting, the processing, the creation

of the threads, the weaving of the materials,” says Christie Byun, associate professor of economics. “It’s incredibly

resource-intensive.”

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, the production of a simple T-shirt and pair of jeans, for example, can consume up to 2,300 gallons of water, from irrigation in cotton farming to the washing, bleaching,

and dyeing. Factors like shipping these materials across continents and the heavy use of plastic-based polyester

further increase the environmental costs.

“Producers have these massive shipping containers and technological advances that make it easy to ship stuff around,” Byun says. “Cotton can be grown in Texas, spun into yarn in India, made into T-shirts in Vietnam, and then sewn in Central America.”

Kevin Hall ’81, a leader of brands in the fashion industry and former president of Champion, has spent decades watching and shaping the shift toward more environmentally responsible production and consumption.

Kevin Hall ’81, a leader of brands in the fashion industry and former president of Champion, has spent decades watching and shaping the shift toward more environmentally responsible production and consumption.

“Across the board, our recycling rates as consumers are very low,” Hall explains. “Plastic still makes its way to the landfill. We need more brands using recycled materials in the production flow.”

The real economics of clothing are complex. Byun points out that while fast fashion has made clothing accessible, it has also encouraged excessive consumption.

“It’s become a race to the bottom,” she says. “Where can we make the cheapest clothing that somebody will wear one or two times before they dump it? People feel virtuous donating it to Goodwill, but 90% of it probably ends up in a landfill.”

According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, clothing production doubled from 2000 to 2014. Consumers purchased an average of 60% more in that span, while keeping those items only half as long. While the clothes look good, often highly decorated with lots of patterns and embellishments, they are designed with the goal of tricking consumers into overlooking the lack of quality.

“That’s to distract from the fact that the materials are so cheap, and if you wear them a couple times, or even if you try to wash them, they’ll begin falling apart,” she says. “The stores are set up like that, too. They have new stock almost every day. They’re gambling on consumers getting addicted to shopping.”

While fast fashion enables middle-to-low-income consumers to purchase more clothing, it creates a hidden cycle of overconsumption.

“We’re cheapskates yet we’re buying more stuff,” says Byun, whose current research project is a book on the economics of the fashion industry. “Somehow, it’s not making us more satisfied.”

Hall echoes the sentiment from an industry perspective.

“The consumer is the boss. They want it cheap, they want it now, and they want it to look good,” he says. “Sustainability can be an afterthought.”

Recycled polyester, for example, is currently up to 10%–20% more expensive than virgin polyester due to processing, sorting, and shipping.

“The easiest thing to do right now is to make new polyester,” Hall says. “The more you recycle, the cheaper it will get. But if the demand for recycled goods isn’t there, you’re back to square one.”

Social media is also having an effect—allowing people in any location worldwide to see different trends as they happen.

“There is a consumer demand for season, colors, and trends, and you have to be able to meet that,” Hall says. “The trick for most manufacturers is that you’re trying to meet global demand with as little product inventory as you can, because product inventory erodes your margins.”

Despite the challenges, some fashion companies are embracing sustainable practices and building their brands around the effort.

Hall now advises StepChange Clothing, a mission-driven brand that uses only recycled materials and donates profits to Force Blue, a nonprofit that reclaims oceanic ecosystems.

“We make socks from plastic bottles. Our T-shirts use up to 16 bottles each,” Hall explains. “We do this because it’s the right thing to do, but it still has to look good and feel good for consumers to care.”

One hope for fashion’s future is circular fashion, the idea that clothes can live multiple lives. Instead of ending up in landfills, materials are returned to the supply chain, broken down, and reimagined.

In between Hall’s time at Champion and StepChange Clothing, he spent nearly two years at Unifi, a global leader in the circular-fashion space. Its REPREVE brand transforms plastic bottles into performance fibers used by companies like Nike, Adidas, Hanes, Lululemon, and Walmart.

“Walmart and Target don’t promote it much,” Hall says, “but they’ve quietly demanded that manufacturers

incorporate recycled materials. They’re driving enormous change from the supply chain side.”

However, textile recycling remains a technological challenge. Unlike plastic bottles, textiles often contain blends of materials that are hard to break down.

“Textile take-back is the next frontier,” Hall surmises. “It’s not as easy to do because most clothes aren’t made of just one material. It takes science and investment.”

Secondhand stores, vintage outlets, and clothing donation programs are simple and immediate ways for the consumer to support the circular economy, but large-scale textile recycling remains in its infancy.

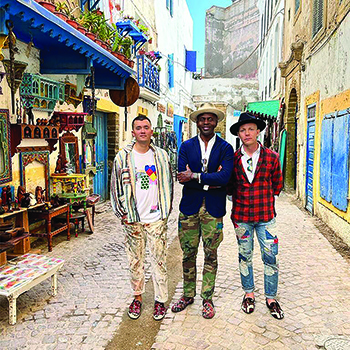

The clothing company Res Ipsa (named after the Latin legal term for “the thing speaks for itself”) takes a slow, deliberate, and personal approach. Everything the company produces is handmade from vintage or repurposed fabrics sourced globally.

“We operate on a different model than almost all other fashion brands,” says Cole Crouch ’17, Res Ipsa brand manager. “Everything is upcycled, repurposed, with zero waste. There’s a story behind every product.”

“We operate on a different model than almost all other fashion brands,” says Cole Crouch ’17, Res Ipsa brand manager. “Everything is upcycled, repurposed, with zero waste. There’s a story behind every product.”

The company’s studio in Marrakesh, Morocco, has had this mission since its founding in 2013. There, leftover fabric from one garment is transformed into something new, such as patches for denim jackets, shoes, or bags.

“We built our own workshop so we could control every part of production,” he explains. “We use every inch of fabric. If something doesn’t sell, we send it back and make something new. You can give fabrics a second life by turning them into something else.”

With eight storefronts (seven in the U.S. and one in Paris), the Marrakesh atelier, and a growing online presence, Res Ipsa is quietly proving that one-of-a-kind affordable luxury doesn’t have to come at the planet’s expense.

“We know we’re not for everyone,” Crouch says. “But the people who get it, get it. And they come back again and again.”

Res Ipsa operates at very low volume, essentially producing only what it sells. There aren’t sales to rid the warehouse of inventory at the end of the season, which allows the brand to meet multiple goals.

“We don’t make a lot of anything,” Crouch says. “There is a scarcity that incentivizes you to want it, but it also helps us achieve zero waste.”

Sustainability often ends up being an internal decision within companies.

“How do you balance capitalism versus sustainability?” Byun asks. “It’s really hard.”

Hall agrees. “Sustainability has to be a key priority from the leadership team. I’ve worked for several companies that made that choice at the top, and the energy often came from younger employees pushing change internally.”

While brands can lead, consumers still hold sway, and they’re not always making sustainability a priority in their clothing choices. According to Byun, clothing expenditures over time have remained almost fixed, but there is more consumption.

“We’re spending the same percent of our budget, even a little bit less than we used to, but we’re buying more clothing items than ever,” she says. “We’ve trained ourselves to think a T-shirt should cost $19.99. That’s ridiculous when you consider what goes into producing quality garments ethically and sustainably.”

Hall believes education is critical.

“There’s a lot of good happening that people don’t know about,” he says. “It would be great if there was a way to get that story out and make sustainability a bigger importance for consumers.

“We’re in the early innings,” Hall says, “but I’m optimistic. When we set a goal of 50 billion recycled bottles by 2025, people laughed. Now we’re going to hit it.”

Ultimately, Byun knows that economics are essential.

“There are really great brands out there doing the right thing,” she says. “You can’t ignore that capitalism and the bottom line drive most of these decisions. It takes courage to change.”