Stephen Morillo’s laugh—almost a cackle—fills every room he occupies. He is just as likely to wear sandals to class as his students, and he religiously plays pick up basketball games at lunch in the Allen Center. At the end of a 34-year teaching career, nearly everyone who has crossed paths with him has a story to share. Morillo’s lasting impact might simply be that he’s someone everyone relates to.

Stephen Morillo is many things—a Rhodes scholar, cartoonist, and world-renowned scholar in medieval history, particularly the Battle of Hastings—but unapproachable is not one of them. He possesses a high level of knowledge on an endless stream of subjects, and he’s happy to engage in conversations with anyone, anywhere, about anything.

“There are so many little things about Dr. Morillo that make you realize these professors aren’t just faces that grade me, they’re human,” says Preston Reynolds ’25. “That’s only part of why students find him appealing. He’s not like any other professor. He’s a bit crazy.”

In the fall of 1988, Bill Cosper ’89 was a history and political science major who was among those chosen to be on the hiring committee for an opening in the history department.

“I vaguely remember one other candidate, but I can’t even really put a face on them,” Cosper recalls, “because Stephen made such a powerful impact.”

He was an accomplished scholar, but Cosper feels his storytelling was what stood out.

“He was able to talk about his work,” he says. “He knew his stuff and he seemed like he would fit with the unique charisma that is Wabash.”

Morillo will be the first to tell you that history benefits from good storytelling, but that aspect in him requires some work.

“I am kind of a natural-born explainer,” he says, “but I have to work at the storytelling. History doesn’t make you a better storyteller. History offers you lots of material to tell stories about.”

When Morillo arrived at Wabash in the fall of 1989, colleagues Jim Barnes, Peter Frederick, and George Davis made up the history department. Barnes, the department chair, taught modern European history, while Frederick and Davis focused on American history.

Aside from those specialties, Morillo jokes that he was hired to teach everything else. The first order of business was to create a world history survey, which debuted that fall. He quickly discovered a creative freedom that came with that blank slate.

“The ability to teach just about whatever I wanted was really freeing,” says Morillo. “I liked doing world history. I was intellectually drawn to that big-picture style of historical analysis. It also let me develop some specializations that I wouldn’t have been able to do at other places.”

Hugh Vandivier ’91 was a junior when Morillo arrived and was looking for courses to fill his distribution requirements. He signed up for History 11: World History to 1500.

“He’s got a sharp wit and his humor was really, really captivating,” Vandivier says. “There was an edginess to him that made students kind of feel like he’s one of us. He’s professorial. He’s incredibly intelligent and a worldwide expert in his field. He’s all of those things and he’s a ‘regular person.’”

Vandivier found the class appealing enough to sign up for the companion class that spring, History 12: World History 1500 to the Present. The wide range of topics discussed, like the impact of the turbine engine, colonization, and globalization, were relatively new topics to a history classroom.

“At the dawn of the ’90s, we’re getting all of these topics in class prior to NAFTA,” Vandivier says. “Dr. Morillo saw the trend of countries grouping together for protection and commerce. His insight was so good. It felt like there was so much forward thinking in the first two classes this guy ever taught at Wabash.”

Reynolds appreciates learning from a professor who is one of the world’s thought leaders on the Battle of Hastings, and appreciates the way he encourages students to think about questions and texts in an in-depth way.

“He’s taught me to enjoy what I do,” Reynolds says. “Dr. Morillo has inspired me to always reach for more. No matter what I came to him with, he immediately thought of an idea to further it. In academia and in life, you always need more ideas, bigger ideas, and critiques.”

Morillo influences his faculty colleagues as much as those in the classroom. Professor of Chemistry Lon Porter calls him one of a handful of influential figures at the College. Often, the ideas he offered at faculty meetings ran counter to the discussion at hand, but his influence was undeniable.

“He just has this presence,” says Porter. “That’s really cool when someone has vigor, a larger-than-life character, and backs it up.”

A handful of years ago, Morillo and Porter teamed up to co-teach a course on naval warfare, one that Morillo lists as his favorite to teach. For Porter, it was a welcome change to work with a colleague across campus and eye-opening to see how Morillo interacted in the classroom.

“He certainly has a plan,” Porter says. “He knows what he’s going to talk about, but what excites me is the way he teaches. He could go in any direction with a student. It was almost like a choose-your-own-adventure book.”

Class discussions would start and questions would come. Porter could tell students were prepared and were ready to participate. Morillo guided the conversation and challenged students with questions like, “What did you think about this?” or “How does this connect to what’s going on in the world in this time?”

“I appreciate that he’s been one of the people to lead the charge in his field to look at historiography in terms of how you connect these things with what is going on in the world. What are the cultures, the people, the economics, these other factors?” Porter says. “That encapsulates this idea of liberal arts in a way that is very impressive.”

Morillo says that his favorite part of teaching is the planning of courses. The possibilities are endless in thinking of what to teach and the questions that follow. The energy comes from a different source.

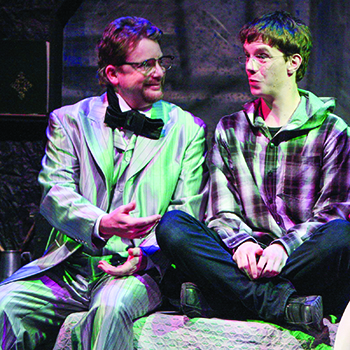

“I like performing,” he says. “I get in front of a class and I’ll talk and organize things and crack jokes. It’s a way of being onstage that I’m in control of. I’m the actor, director, and writer put together. And that’s a lot of fun.

“The moments in class where everything comes together—it’s the right readings, the students are doing well with them, and I’m on—I just walk out of the class saying, ‘Yeah, that was exactly what we wanted to accomplish there,’” he continues. “That’s when it really works.”

Thinking of a colleague who joins the ranks of emeritus faculty, Porter pauses for a moment to ponder Morillo’s legacy.

“Whether it was a smile or a laugh, he had a way to make you feel like you belonged in the conversation,” Porter concludes. “He’s a superstar in his field, but at the same time, he’s found the magic sauce to allow him that elusive balance between doing what you love and being really amazing at it, but also having that kind of protected realm of staying balanced and enjoying life.”