If you have never been detained in a hostile foreign country, consider yourself very fortunate. The repercussions can be grave, if not life-threatening.

That is what happened to me in August 1958, in West Berlin, Germany, when I boarded a train to begin the first lap of my return to the United States.

The journey began in September 1954, when I enlisted in the Army Security Agency (ASA) after getting my degree at Wabash. Two months of basic training were followed by six months of learning to speak German at the Army Language School at Monterey, California. Most of my remaining tour of duty was spent with a small detachment on the East/West German border.

Although our activities were secret, we were also required to guard and defend the compound.

Following my discharge from the Army in November 1957, I decided to use the GI Bill to finance an extension of my liberal arts education at the Free University in West Berlin and have something of an adventure as well. I journeyed to Helmstedt by rail. Helmstedt-Marienborn was Checkpoint Alpha—the most important border-crossing checkpoint between West Germany and Soviet-occupied East Germany—by rail or by the federally controlled highway system, the Autobahn.

To get to Berlin by rail, all passengers had to buy a visa from East German grenzpolizei (border police) on the train before it left the station. The visa was valid only for the trip. The police also examined passports of those from foreign countries. The train made no stops until it reached Checkpoint Bravo in a wooded area at the southern borough of Dreilinden. Border police there checked our visas and passports again before the train continued to the station in West Berlin.

For the next four months, I lodged in a room with a German family. Social activities were not ignored, and I made some friends on the university tennis courts, where, as a former member of the Wabash tennis team, I held my own against my opponents. After raising a sweat on the courts, we usually headed to a pub for some beers.

For the next four months, I lodged in a room with a German family. Social activities were not ignored, and I made some friends on the university tennis courts, where, as a former member of the Wabash tennis team, I held my own against my opponents. After raising a sweat on the courts, we usually headed to a pub for some beers.

I was tempted to remain in Berlin for another semester, but was reminded by letters from my parents in Kokomo, Indiana, that it might be about time I came home and got serious about my life. At a travel agency, I booked passage on a ship that would transport me from Bremerhaven to New York City. This required traveling by rail through East Germany to Hamburg, where I would board another train to Bremerhaven. Looking forward to the voyage, I packed my suitcase, strapped on my tennis racket, and boarded the train to Hamburg at around 9 a.m.

When the train stopped a few minutes later at Checkpoint Bravo, the border police fanned out through the cars to check passengers’ documents. After one of them looked at my passport, he asked to see my visa. I told him that when I came to Berlin I bought the visa on the train. He glowered at me and said, “Kein visa? Steig aus dem Zug!” (No visa? Get off the train!) There was no use arguing with him—not with the revolver in his hand pointed at me. I picked up my baggage and got off the train.

The policeman marched me across the expansive grounds of the compound occupied by a cluster of buildings, barracks, and a motor pool of vehicles. On the way, I observed two policemen on a tower monitoring the area through binoculars. Many other policemen were engaged in various activities. All were armed with sidearms, automatic weapons, or both. Soviet troops were also present.

An officer emerged from a small building as we approached. My escort handed him my passport and explained that I was removed from the train because I had no visa. While the officer examined my passport, I asked him if I could buy the visa there. “Nein!” was the answer. And I was told I would be detained until further notice. He summoned a policeman to escort me to a detention facility. He did not return my passport.

About 30 people sat on wooden benches looking very uncomfortable. There were no windows to allow for some much needed outside air to provide relief from the heat. The only source of ventilation flowed through the open entrance door, where a young policeman sat with a submachine gun on his lap. He greeted me with a scowl and told me to take a seat. I did, with my baggage at my feet. Two hours dragged by. More people arrived and others were taken out by policemen. The longer I sat there, the more apprehensive I became about what was in store for me.

An hour later, I had to be escorted by another policeman to a large outhouse occupied by a convention of flies to relieve myself. On my way back to the detention facility, I tried to get some information about getting a visa. I learned I would have to go to the Ministry of Transport in East Berlin. Hourly commuter trains went to and from the checkpoint and the train station in West Berlin. That was the good news. The bad news was that, being an American, I would be questioned by an intelligence officer before I could leave the checkpoint.

After several more hours in the detention facility, another policeman appeared and called my name. He told me to pick up my baggage and follow him. When I entered the new building, my heartbeat jumped when I saw the man behind the desk of the reception room. He was wearing a uniform, but it wasn’t a German uniform. It was Russian!

He told me in German to sit down. But when he spoke through an intercom, it was in Russian. After listening to another Russian voice on the speaker, he rose, opened an office door, and said: “Geh hinein!” (Go in!) I left my baggage there and entered a plainly furnished office with filing cabinets and two chairs facing a desk. The man behind the desk was middle-aged and robust looking. He had a strong face with cold, crafty eyes that focused on me like lasers. I knew instantly that he was KGB and I was in for more than just “questioning.” It would be an interrogation!

He waved me into a seat and began by confirming the information in my passport, which now resided on his desk. His first question: What was I doing in Berlin? I replied that I was a student at the Free University for a semester and gave him my student ID card. Then he asked where I had learned to speak German.

Not good, I thought.

I couldn’t tell him the truth. He would know that as an attendee of the Army Language School I had been involved in some kind of espionage as practiced by the ASA and Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC). I told him that I had studied German at Wabash College. He picked up a pen and asked when I attended Wabash and where it was located. He wrote my answers on a notepad.

Had I served in any branch of the United States armed services? Since he had to be aware that there was a draft at the time, I informed him that I had served in the army from November 1955 to November 1957. And where I was stationed? he probed. I thought fast. I had gotten together a couple of times with a fraternity brother in Frankfort who was stationed with an infantry unit in Mannheim. I told the officer that’s where I was stationed.

The rest of the Q and A became more intense and went something like this. “You say you served in the infantry.” “Yes.” “Were you required to speak German as part of your activities?” “No. But it helped with my social life.” “Are you sure about that?” “Yes.” “Do you know about the Army Language School?” “No. Where is that?” “In Monterey, California. Several languages are taught there. This includes German. The soldiers are taught these languages so they can conduct espionage activities.” “I didn’t know that.” “Are you sure? Your German is quite good. You could have learned to speak it there.” “No. It was at Wabash College and the Free University.”

He continued to ask the questions again, perhaps looking for a slipup in my answers. After I responded with the same answers, he stared daggers at me and started tapping the pen on the desk. He was not buying my story.

“I may have to keep you here until I find out if you are telling me the truth,” he said.

I made a supreme effort to keep my cool as he continued to tap the pen. When it came to gathering intelligence, the KGB got an A-plus. I knew a phone call would be all it would take to check my story and find out it was bogus. At which point I would be escorted under armed guard to Stasi headquarters, East Berlin’s State Security Service, for further interrogation, and that wouldn’t be gentle. From there I would simply disappear. If I was lucky, I would go to a Gulag labor camp in Russia. If I wasn’t, I’d be in an unmarked grave. I was briefed on this prospect by an ASA intelligence officer while I was stationed at the field compound on the East/West border.

When he reached for the phone on his desk, I held my breath, hoping for the best. I felt like I’d stepped into an empty elevator shaft. But before he picked up the receiver, the phone rang.

From what I could gather from his side of the conversation, it was with someone named Karen—not his wife but his girlfriend. And she was not happy. He kept trying to explain why he couldn’t be with her that night. He had to take the place of an officer who was ill. I had no idea if this was true or not. But it was obvious that Karen was having a hard time believing him.

As this altercation continued, I took advantage of his distraction to interject. “I have to get my visa at the Ministry of Transport. I understand there are commuter trains to West Berlin. When can I leave to get the visa? If I don’t get to Bremerhaven tomorrow afternoon, I’ll miss the boat!”

I could see the frustration mounting on his face as he tried to listen to me and console Karen. Finally, he said to her: “Ein moment, Liebchen” (One moment, Love). He laid down the receiver, stamped my passport, handed it to me, and said: “Sie können jetzt gehen” (You can go now).

I got the hell out of there, pausing only long enough in the outer office to pick up my baggage before boarding the next commuter train to West Berlin. I parked my baggage in a locker at the station and used a 50-pfennig coin in a phone booth to call Manfred, a tennis buddy. I needed to get to the Ministry of Transport, and Manfred had a motorcycle. He picked me up half an hour later. After checking our IDs at Checkpoint Charlie (this was before the infamous wall was built in 1961), an East German policeman gave us instructions on how to get to the ministry. When we arrived, it came as no great surprise that the ministry was closed.

New game plan. My only way out of West Berlin now was to fly. Next stop was the travel agency, where I purchased a ticket for a Lufthansa flight to Hamburg that would lift off at 8:45 p.m. That gave Manfred and me time to stop at a pub before I picked up my baggage at the train station. With me perched precariously on the tandem with my baggage, we zoomed on his BMW cycle through traffic to Tempelhof Airport. Bidding Manfred auf wiedersehen (goodbye), I boarded the plane, flew to Hamburg, took the train to Bremerhaven, and arrived just in time to catch the boat and the usual fanfare that precedes an ocean voyage.

I had my own way of celebrating that voyage. As I stood at the rail with a martini, watching the Bremerhaven skyline recede in the distance, I raised the glass in a toast to the girl who had saved my life.

“Danke schön, Karen!” (Thank you, Karen!)

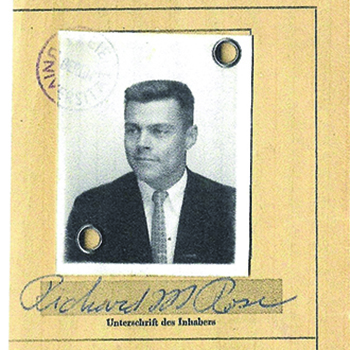

Richard Rose ’54 is an award-winning author and screenwriter. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Kay.