One of Usby Bert Stern |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

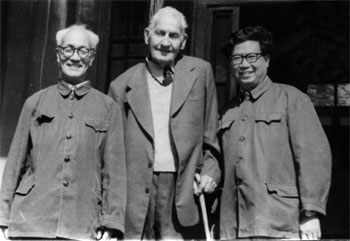

In 1979, the Wabash Admissions Office received a note from a mysterious man in China. He announced himself to have graduated in 1909 and staked claims to being the oldest living alumnus. But the real purpose of his letter was to recommend a young man named Rujie Wang, whom he had helped educate. Rujie proved every bit as good as the letter promised. He was challenging—always hungry for just a little more than I gave him in the several classes where we met, and more than ready for graduate school. We soon became friends and met often in my office and home. We talked about literature, but we also talked about China. He spoke with intensity about his experiences in the Red Guard, Mao Zedong’s band of fanatical young people who were the vanguard of his attack on traditional Chinese culture. Rujie’s parents, both professors of English at Peking University, were bright emblems of that culture, and the stories Rujie told about confronting them as enemies were deeply disturbing. He told the stories like a man who wanted to get them off his chest, and he told them with agonizing remorse. Rujie also talked to me about Robert Winter, the man who had recommended him, and I was fascinated with his tales of a Crawfordsvillean who went to China in the 1920s, just two years after the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, and remained there almost without interruption until the time of his death in 1987 when he was 100 years old. At a certain point in my listening I knew in the way one knows only once or twice in a lifetime that I, too, must go to China. That is how, in the early fall of 1984, I found myself with my wife and five-year-old daughter —all of us jet-lagged—wandering around the campus of Peking University, with its tiled pagoda-style buildings, carved lion guardians, lakes, and copses. On the edge of one such grove we saw maybe a dozen people practicing tai chi, moving like beautiful ghosts in the half-light. We knew we were a long way from home. “To Be Rich Is Glorious” The old neighborhoods of densely populated houses on streets too narrow for cars and rich with vegetable and flower gardens were being displaced by hideously inhuman concrete towers, housing tiny apartments whose ceiling and floor and walls were also raw concrete. Faculty housing at Peking University, “the Harvard of China,” was no better. But our own apartment in a “foreign experts” compound on the campus was comfortable enough, and even included a television set. We didn’t understand Chinese, so we rarely watched, except for our favorite program, which aired daily just before supper. It featured a live camera on Tiananmen Square that would zoom in on unsuspecting female tourists for examples of what not to wear. The show was ahead of its time—back then the nearly universal dress for men and women was still the dark blue Mao suit. Our daily lives soon fell into a pleasant routine. I taught three classes but had no other obligations at the university except for an occasional banquet. So my life, like my family’s, was simple in a most un-American way. I especially remember the absence of noise and paper pollution. There was no traffic on campus, except for the occasional maintenance truck or horse cart. And there was very little paper. You didn’t see scraps of it anywhere—not newspapers, not flyers, nothing. Paper was a precious commodity, used and endlessly recycled. As for noise, in the morning and evening, a very harsh woman’s voice beat out cadences during the compulsory exercises for students and faculty in the courtyards. Early on clear mornings a single bird song might ring with remarkable clarity. Our pace slowed dramatically. Riding downtown in a mass of fellow bikers, we for once felt part of the crowd. In the evening, sometimes we’d see rare displays of simple public affection—young lovers riding hand-in-hand down a dimly lit avenue. “Red Stars” in My Eyes My writing students were fascinating in a special way. With them the teaching was reciprocal. I taught them how to write—and also how to think, because thinking was more of a liability than an asset during the Mao years, and was still a bit dicey even in this calmer time. They taught me China. In a student essay I’ll never forget, a shy girl described how, when she was five or six, her parents spent the whole night guarding their pigs from a marauding tiger, leaving her alone in the house. She said nothing about her terror, nor in any way presented the experience with bitterness. She just described it. It was years before I really understood her story. I simply couldn’t negotiate the cultural abyss and the bald fact that the pigs were more valuable than the girl, as was true generally, and probably still is, in Chinese agricultural areas. For several months I was taken in by my hosts’ skill at putting China’s best foot forward. We were taken on field trips—to operas, museums, and to People’s Liberation Army camps, where we were shown the many ways that the army befriended the rural environs around them. We ate up these visits, utterly convinced that the society we were visiting was compassionate and in love with its own culture. It’s painful for me to admit that I went to China with “Red Stars” in my eyes. I wanted badly to find a utopia in China of the kind that Mao sometimes saw himself as creating. I honestly regret the loss of such political innocence. It was a kind of innocence that kept alive my hope for the human species. But I should have known better. Rujie’s stories of the brutalities of the Cultural Revolution should have been enough. And there were other clues around me. But hadn’t I found in the writings of the illustrious Harvard historian John Fairbank glowing pictures of Mao’s China, pictures consistent with my own dreams? It took me awhile to see through such delusions. “Can You Get Me Out of Here?” During and after the Cultural Revolution, the Party officially ostracized Winter. That left the 97-year-old man high and dry in a single room of his small house on the edge of the campus. Around it were scattered ruins of his once-magnificent garden, but the man himself was confined to a rumpled cot. Though I didn’t know it at the time, he was often drugged to calm the rage and other passions that otherwise could overwhelm him. His regular companions in the house were vaguely sinister. These were Liang, a kind of male nurse who sometimes gave Winter massages and who remained a shadowy figure to me, and Wang, Winter’s cook and housekeeper, a former prostitute who started to work for Winter after he rescued her from a crowd intent on beating her. On my first visit the housekeeper let me into a space that was cramped and almost squalid. It smelled of a sick room. But fabulous objects were scattered around as relics of a livelier past. A classic carved teak cabinet covered one wall. (How Winter managed to preserve it through the wars and exiles he endured, I can’t imagine.) Other vestiges of Winter’s earlier lives hung on the walls. A Qing Dynasty painting depicted a mustachioed man in a red cloak leading a camel though snowy mountains. Both the man and the camel are staring with a kind of sublime haughtiness at the clear mountain sky. It is a traveler’s picture, and it celebrates solitude and fearless quest. A self-portrait in oil depicted Winter himself as he was perhaps 50 years earlier: big, boldly mustachioed like the horseman, and very handsome in an imperious, British kind of way. Another painting by Winter, which I now own, showed a young fisherman looking directly at us, holding a small sea horse in his right hand. It is unmistakably erotic, even if we don’t know that the sea horse is an erotic emblem in China. Finally, over Winter’s bed hung a Wabash pennant and certificate of merit in recognition of the College’s discovery of him as its oldest alumnus. In the midst of all this, prone on a narrow bed, a gaunt man lay immobile, except when he coughed. One of the first things the old man said to me after he’d roused himself was, “Can’t you think of some way to get me out of here?” It was a terrible question. “Here” was not simply this house. It included the dead end in which a man who defined himself by his activity had now arrived in this house, with its slightly shady attendants, this terrible state of mind and body. He was like a great fish washed up on the shore, breathing out his last. I could not think of any way to get him out of there except to record his life, moving with him from his dead present to his vital past. Early on I imagined that we would reconstruct his life together and that, in the realized form of what he had been, he would find freedom from remorse. He had a great measure of that. He told me that he had wanted “to blot himself out.” He never had personal ambitions, he said. He had “wanted to be nothing.” Why did people— that is, me—come to see him now? He really wanted to know. He felt himself to be a man disgraced. The most heroic of his efforts on China’s behalf during World War II were turned to dirt by the humiliating brainwash sessions he had been subjected to by Party officials. Now, he wanted to be told—by me, by anyone—whether his life had meant anything. “What do the Chinese think of me?” he wanted to know. Would I ask his servant Wang? I can’t ask, I tell him—I don’t speak Chinese. “Let that man translate,” he says, pointing to Liang, one of his attendants. Liang speaks to him quietly, holding his hand, rubbing his back softly with the other hand, and telling the old man what he wants to hear, thus giving him the only steady love that he can expect. But old Liang with the milky cataract in his right eye doesn’t speak English. “You’re the only one who can translate,” I tell Winter. “Shall I call in Wang?” She comes in. In Chinese, as if he is conducting an interview, Winter asks Wang his constant question: “What do the people of China think of me?” She answers, and he translates to me, almost disinterestedly. We seem to be actors in an absurdist drama of most perplexing vectors. “Fu Yi, Wen I-to, Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai—they all say you are a good man,” Winter says. Then Liang begins to speak carefully, formally. And the old man translates, in a scene that might have been written by Beckett: “I am a true friend of China. I did very important things for China. The Chinese like me very much. China was very different because I was here. Both students and teachers…” “Lin Chou [a well-known geographer who had once been Winter’s neighbor], Chen Deison [under Mao, China’s leading economist], Chou Peiyuan [who was President of Peking University in the 70s]…” Wang says. “Those are just names,” Winter remarks to me. “People who admire you,” I say, “real friends.” He smiles, for the moment appeased. So these surreal interviews went. Yet sometimes this gaunt man with a bad chest would gather himself, and the full, commanding timbre of his voice let me see him as he once was. Moments of his past life and stature would flash into brilliant relief. Still, when I later described my project to the translator Gladys Yang, she shook her head ruefully. “You’re dealing with clouds,” she said. Born to Internal Exile He’d grown up in Crawfordsville at the turn of the 20th century, born to internal exile. His family was disorderly, and he acknowledged nothing positive about his life at home. He knew early that he was gay. As if that weren’t bad enough, he was also bookish, a young man whose real life was increasingly in the borrowed worlds that his reading opened to him. Then, as a freshman at Wabash College, he met the young poet Ezra Pound, who taught briefly at the College and, like Winter, was straining to leave almost as soon as he arrived. Pound was the very embodiment of the culture Winter hungered for. Not only did he open Winter more deeply to the powers of poetry, but he also handed him the magical formula for Winter’s escape. “Pound told me,” Winter said, “that I must go out and seek my teachers.” Winter’s journey to those teachers and to freedom came in fits and starts. He studied for a while in France and Italy, then returned to teach at Evanston High School, where he was already deeply interested in things Chinese. Later he got a minor post as a French teacher at the University of Chicago, where a second chance meeting sealed his fate. Wen I-to, already one of China’s leading poets, was in Chicago in the early 1920s to study painting at Chicago’s Art Institute. That’s where he and Winter met, standing in front of a picture. They began to discuss the painting. They were quickly dazzled by each other. For Winter, Wen was the embodiment of the culture Winter was already absorbing from a distance. And to Wen, Winter was the most extraordinary American he’d met, because of his depth of knowledge and passion he had for all things Chinese. On his first visit to Winter’s apartment Wen saw a remarkable painting Winter had made from an ancient drawing of the Taoist Lao Zi. Nearly all Winter’s furnishings and objects were Asian, from China and India. Winter even burned oriental incense when Wen dropped in. And they talked endlessly about Chinese poetry. Then something dramatic happened. Winter had to get out of town, fast, perhaps because of a homosexual indiscretion of the kind that haunted him almost to the end of his life. Wen wrote letters, and in 1923 Winter sailed to China to take up a post at Nanking University. Before long he was able to move to Peking, where he got teaching posts—first at Tsinghua University and, after World War II, at Peking University. Winter was a fabled teacher at both these posts, and his first 10 years in China must have been perfect bliss for him. Not only students but also Western and Chinese peers gathered around him, not only for his famous stories but because his home was a cultural center—a place where intellectuals, traditional and modern, gathered often for performances by famous musicians. Winter also had an extensive collection of classical music by German composers, and he would offer weekly concerts for which he provided programs, and would talk knowledgeably about the composer and the piece to be played. For much of his life in China, Winter was the only embodiment of Western culture. During this period, Winter also came as close as a West-erner could to becoming a Chinese Mandarin, master of traditional arts and crafts as well as a fluent speaker. It was as if he’d died and found himself in a heaven of culture, where he often stood in the central role that he enjoyed. He loved to be fascinating, and had great gifts for it. His companions were people who embodied the 5,000-year tradition of Chinese culture—its history, its manners, its morality, its high aesthetic. Keeping a Flame Alive But eventually, for all his indefatigable energy as caretaker, Winter was forced to follow his colleagues to Kunming, where bombings, hunger, sickness, and horrifying sights of the dead and dying became his daily fare. Scurrying for shelter against Japanese air raids, Winter learned what it was to strip away pride and reach the condition of Lear’s “poor, naked, unaccommodated man.” And I think that it was this that a former colleague of his meant when he described Winter to me as “one of us.” Yet even during this terrible time, he continued to teach, as if keeping a flame alive. His Shakespeare class was legendary. He could recite great swaths of the plays from memory, and, a natural-born actor, performed them by adapting his voice to each of the characters, and even, when the text required, burst into song. Students crowded into his classroom, and outside, too, to hear Winter through open windows. More an Afterlife Than a Life But despite Winter’s many acts of heroic resistance, the postwar brought him little good. In Maoist China anti-imperialist feeling ran high, and Winter’s association with the Rockefeller Foundation, who had sponsored the Basic English project he’d helped to organize, led the Chinese to suspect him as an American agent. Although he was allowed to keep a symbolic post at the university, his role was now the humble one of writing English language exercises. His old friends feared to talk with him, so he lived for decades in a different sort of internal exile—he who had cut so brilliant a figure in the eyes of his American and Chinese friends and co-workers. Although that final stage was more of an afterlife than a life, as long as he could walk, Winter’s observation and love of nature served to replace the broader cultural world of which he’d been so vivid a part. His house was surrounded by lovely lotus ponds that gave Winter peace and strength against his troubles. Now, in his last days, he’d lost even that simple pleasure. A Fearless Man of Action The old man I came to know—though lucid only in fits and turns and deeply demoralized by cold interrogators who treated him as an enemy of the people—was a great man not only in my eyes, but also in the eyes of people far closer to him than I. What they loved in him, beyond his ability to entertain and captivate, was his personal modesty. He never aspired to be a great man, nor ever thought of himself so. And he took as much interest in the simplest peasant as he did in his refined associates. He was a teacher, a clear thinker, a fearless man of action. That was his nature. He had traveled far to find the perfect refuge, but in the end, that refuge vanished in smoke, and he was left just as alone as he began—an outsider in Beijing as once he’d been an outsider in Crawfordsville. Yet there’s something that prevails in the man that I can best point to with a story. In 1945, back at Peking University, Winter returned to his house one afternoon to find it crowded with students. They had come to hear a Mozart concert Winter had selected from his many albums. Just as the concert ended, word arrived that full-blown civil war had broken out between Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist and Mao’s Communist troops—this on the very day, indeed, at the very moment, when Japanese troops were formally surrendering at Yiogk’ou. The students who had been cheered by the music now hung their heads. All hope that the years of fighting would end with the Japanese surrender was lost. The students apologized to Winter for their country. Dejected, they were about to leave when he called them back and prompted a discussion about the power of art to console at such moments. He quoted Rebecca West’s daunting question: “Art covers not even a corner of life, only a knot or two here and there, far apart and without relation to the pattern. How could we hope that it would ever bring order and beauty to the whole of that vast and intractable fabric, that sail flapping in the contrary winds of the universe?” Yet after throwing out that terrible challenge, Winter maintained that when you feel at the end of your tether, “music can act as a kind of starch which freshens up a soiled and shabby mind and makes it presentable again for a while.” Then he reminded the students of the old man who had lived across the street from him and who had captivated and inspired war-weary audiences for years with his performances of songs about mythical emperors who had supposedly lived more than 4,000 years ago. The old singer “was a living skeleton and his arms and legs showed like broomsticks through his rags,” Winter said. “He had made a sort of drum by tying a piece of leather over the end of a length of bamboo, and he used the drum to accompany his song. When a crowd had collected round him he would march solemnly in a circle three times, stopping after each circuit and striking three majestic notes on his drum to underline the grand passages. "It was astonishing to watch the faces in the crowd and to see the solemn interest that they took in the deeds of men whom we now think never lived at all.” The story needed no commentary. It spoke to something that prevails, if only in song and in memory. Mozart himself died a ragged figure. Winter did, too. But their lives and works, as different as they were, are songs that people will always keep singing.

|

The beginning was out of the blue.

The beginning was out of the blue. I taught one writing class and two literature classes. Except for the graduate students, most were interested in polishing their English rather than mastering the treasures of English literature. There were brilliant excep-tions, including a young man who went on to become one of China’s leading poets.

I taught one writing class and two literature classes. Except for the graduate students, most were interested in polishing their English rather than mastering the treasures of English literature. There were brilliant excep-tions, including a young man who went on to become one of China’s leading poets.