Daughters: Wabash Daughterby Alison Baker |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

When she said, "How’s your family? All those brothers?" I knew why.

You know how memory is said to come flooding back? It does, and it did, and riding the crest of the wave were my six imaginary brothers. I choked out something about how everybody was just fine, cut the conversation short, and sat in my kitchen a little bit stunned.

In years of letters to my unsuspecting friend, I had waxed eloquent about my big family. I’d told her everything I could think of about my brothers: their full names, their hobbies, the sports they excelled in, the scholarships they’d won. In letter after letter I reported on their graduate degrees, their weddings, their wives and children, their careers. Naturally, they were all much older than I; they were from my mother’s first marriage. To a physics professor. I was a little fuzzy on what had happened to him; but once he was out of the picture, she married my father and produced my sister and me.

My heroic English professor father had taken on her six sons and put them all through Wabash.

Of course, the truth was that I possessed one measly older sister who had as little to do with me as possible, and my parents had been married to each other since World War Two.

But my brothers weren’t complete fabrications. Every day a stream of boys passed our dining room window on the way to class, and I had selected a few I liked: the red-haired guy who always stopped to pet my dog. The one who traded puns with me over the hedge. The tall one who ran over to pick me up when I crashed my bike into the brick wall across the street. I took my pick, changed a few minor details—like their parentage—and there they were: a whole set of fictional characters to do with as I pleased.

How had I forgotten them for 40 years?

And how had I ever conceived them to begin with? (If one can be said to conceive one’s own brothers.)

I suppose it’s not so mysterious: pluck up a little girl who’s prone to daydreams, deposit her on the campus of a men’s school, and what’s she to make of it? My first years in Crawfordsville were in a neighborhood of old ladies and lots of kids; but then we moved to the edge of the Wabash campus, behind the Beta house and on the

A shy child who liked to read in my room, suddenly I felt that I was on display. Dr. Baker’s daughter. A girl. In the years that followed, not once did I set foot on campus without a sense that I was being watched.

And yet I might as well have been invisible. There was nothing for me in those echoing brick buildings that smelled of floor polish and pipe tobacco; the students for whom they were built were boys. Education was the closest thing our family had to religion, and certainly my parents encouraged me to believe that I could do anything I wanted; it never occurred to me that being a girl was a handicap. Yet what was the evidence? Day after day, off went my father to his important work of teaching boys. Every one of his friends and colleagues was a man; "female professor" was an oxymoron, the punch line of a joke. Women at Wabash were wives or secretaries or cooks. Or they were Dates, those well-groomed weekend visitors who had disappeared by the time real life began again on Monday morning.

Most of the time I felt like a trespasser.

That’s what I see from here, so many years later. What growing up at Wabash meant to me then, who knows? I can’t remember my thoughts, or myself, really, at that age. (My old diary, the one with the little lock and key, is singularly unhelpful; a sample entry from 1963 reads October 17. Today I collected 937 buckeyes.) But I can guess that a solitary child at the edge of a group she can never be part of might imagine a way to be included. Might invent a big happy family. Might supplement her meager supply of siblings with a half-dozen kind and protective big brothers who paid attention to her now and then.

I called my old friend back. "I have something to tell you," I said. "I don’t have six brothers. I made them up."

A true friend, she started to laugh. "You’re a hoot," she said. "What an imagination!"

What makes up anyone’s interior life? It’s such a vast mosaic of experiences, jumbled together and contradicting each other. Scrambled into mine is also the occasional winter night when the invisible little girl would go out with her father into the crisp cold darkness, Orion and the Milky Way bright overhead. We pass through all those little doors in the walls behind the library and the Campus Center, coming out at the old Armory. My glasses steam up as we join the crowd pushing through the foyer into the gym, peeling off mittens and scarves. We climb the bleachers, halfway to the ceiling, through noise so loud I can hardly hear. The team comes pounding out in their scarlet uniforms, and they thunder up and down the gleaming yellow floor, tossing the ball back and forth, leaping and dropping it into the basket time after time.

All around me people stand up, and I stand up too. No one can see me in this crowd. We all stand together, suspended for a few seconds, waiting; and then we burst into song, sliding down the hills of Maine to the western plain, or to where the cotton is growing. More than 40 years later I can still sing it for you. I don’t know all the words, or even many of them, but I know Our greatest joy will be to shout the CHOrus!

Dear old WaBASH! Tucked in among those deep voices is mine, singing my hungry little heart out in that hot gym. As if I were part of something. As if I too were a loyal son.

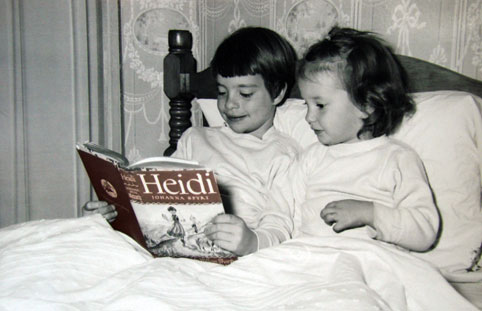

Photo: Pamela and Alison Baker

|

Awhile back I got Googled by a childhood friend. We’d met one August at the beach, and for years afterwards we wrote to each other, until somewhere in high school the connection petered out. So when she called me out of the blue, I was surprised and pleased; but as we chatted, catching up on each other’s lives, I felt a little uneasy.

Awhile back I got Googled by a childhood friend. We’d met one August at the beach, and for years afterwards we wrote to each other, until somewhere in high school the connection petered out. So when she called me out of the blue, I was surprised and pleased; but as we chatted, catching up on each other’s lives, I felt a little uneasy.