Child of the Starsby Steve Charles |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

In July 2003, on the eve of an historic mission to Mars and with the fulfillment of his childhood dream within his grasp, Suniti Karunatillake ’01 was awakened by a nightmare.

"I was viewing the launch at Cape Canaveral and had started to drive away when the Delta launch vehicle diverted from its course and headed in my direction," Suniti recalls. "It crashed moments later."

The premonition was no flight of fancy—engineering errors had cost NASA the Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander in 1999. A Delta III rocket had crashed in a fireball into the Atlantic just after launch in 1998, and a Delta II—the same type of vehicle carrying this Mars mission—had exploded 13 seconds into flight in 1997.

The space agency was still reeling from the loss of seven astronauts aboard Columbia in February 2003, when the nation’s first and most dependable space shuttle disintegrated during reentry.

To a jaded public, failure was becoming the status quo at NASA.

Karunatillake doesn’t believe in premonitions. As an "apprentice" to Steve Squyres, the Cornell University astro-nomer and principal investigator for the twin Mars rovers Opportunity and Spirit, he realized that he might have just picked up on some of his mentor’s own anxiety about the historic flight.

Yet years earlier he’d ignored a dream in which the father of his best friend died of a stroke. Writing off the premonition to a hyperactive imagination, Suniti was horrified to hear the next day that the man had suffered from a stroke that eventually proved fatal. He had vowed never to dismiss such dreams again.

But there was no stopping the launch of Mars Opportunity.

"Launches are complex decisions that cannot?yield to the premonitions of an individual," Suniti explains.

Hoping for the best, Suniti followed the launch on NASA-TV on the night of July 7, 2003.?Just 20 seconds before launch, the countdown was halted because of a possible malfunctioning valve. When the countdown resumed in less than 30 minutes, he feared the worst.

Seconds later, the Delta II rocket carrying the second rover of the Mars Exploration mission destined to become the most successful effort in the history of interplanetary flight roared through the night sky.

"As it leapt to the heavens it banished my nightmare to the dark depths of my mind," Suniti recalls. "I slept soundly that night."

Suniti says that he’s always been a dreamer.

"I have always loved learning how things work, and exploring beyond the confines of our planet became a childhood dream for me," he recalls. "In elementary school, I kept journals about moon explorations and the astronauts.

As a teenager in Sri Lanka, I became interested in Carl Sagan’s notion that we are ‘the children of stars.’ I would spend hours stargazing, telling unidentified civilizations out there that we would communicate with them one day."

An avid reader of science fiction, he was drawn to the works of Sri Lanka’s most famous resident, 2001: A Space Odyssey author Arthur C. Clarke.

"Science fiction always helped me think beyond the current reality, of what may come when we become a space-faring species."

Thinking beyond the current reality was a necessity for an idealist in Sri Lanka during the 1990s, as violence flared up once again in the nation’s long-running separatist war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. But dreams of exploring the stars took a back seat when Suniti needed to focus on the biology, math, and physics he studied as a Wabash physics major.

Still, Suniti says that work made pursuing his dreams possible once he reached Cornell.

"I had imprinted on Cornell as a child like a fledgling does with the first animated object he sees," he explains. "I was six years old and Cornell was the first university I had seen—it seemed much bigger than life. It had the aura of a kingdom of inquiry."

The young physicist had reached the place of his dreams, but he’d yet to discover his field. And though he enrolled at Cornell as a doctoral candidate in the physics department, "the call of the planets" lured him elsewhere.

"I was browsing through faculty Web sites in the hope of finding somebody who shared my outlook on the universe. It was more a search by gut feeling than it was an analytical search.

That same week, Squyres was looking for a graduate student.

"I told him of long wanting to explore planets. I told him I was from a small college—Wabash—and he said he was happy with its reputation," Suniti says. "Though a strong disbeliever of fate and a questioner of all religions, I sometimes wonder whether it was something beyond coincidence.

"Steve warned me. He said, ‘Think this through before you give your word, because spacecraft just die and NASA loses funding all the time; there are no guarantees in space exploration.’"

As one Cornell web site describes his work, he’s learning "the story of Mars."

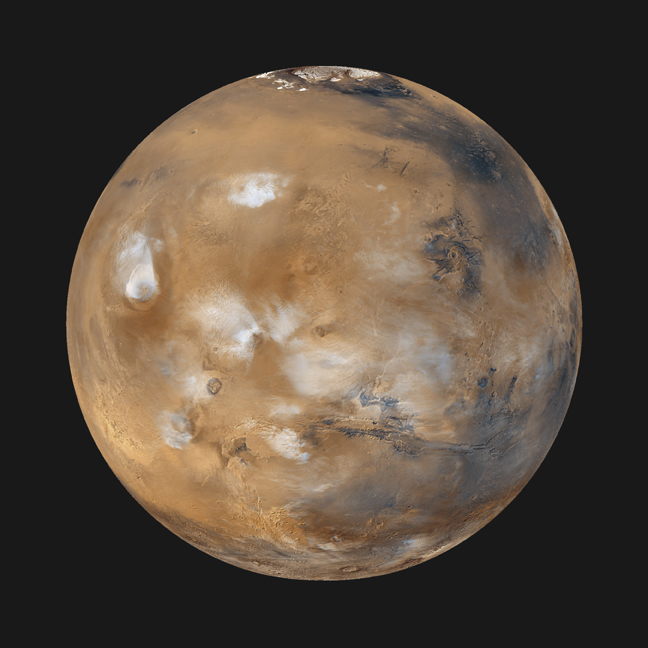

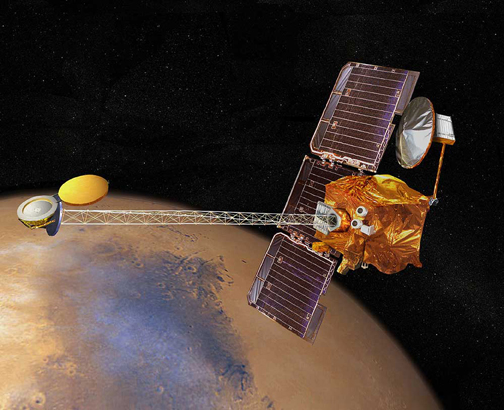

His chief instrument thus far has been the gamma ray spectrometer (GRS) aboard Odyssey. The GRS detects the presence of elements from the periodic table by measuring gamma photons emanating from the planet. These readings enable the astronomer and his colleagues to create geochemical maps pinpointing the presence of several elements on Mars. These elements reveal much about the planet.

"This tells us that Mars may have had compositionally different regions in its mantle, which has implications on how the whole of Mars evolved geologically," Suniti explains.

While not as sexy as still photographs from the Martian surface, these gamma ray "pictures" have provided some of the most memorable moments of the mission for Suniti and his colleagues.

"Steve was showing me the hydrogen peak in the gamma photon spectrum," Suniti recalls, "and I realized this was the first time humans were seeing direct and indisputable evidence for hydrogen on the Martian surface on a truly global scale."

Of course, hydrogen is a key ingredient in what explorers most hope to find evidence of on Mars: water. But for Suniti, the panoramic camera aboard Opportunity provides the strongest case for water’s presence. He remembers the first time he saw the smile-shaped "festoons" on rocks in the planet’s Meridiani Planum region—the "cross lamination" that on Earth forms only in flowing water.

"When I saw those pictures, I could visualize an ancient Meridiani Planum with pools of water in places and flowing water in others," Suniti says. "Now whenever I see ripple marks on compacted beach sands—or even the cross-bedding on rock outcrops in Turkey Run State Park—those pictures come to mind."

Suniti’s meticulous exploration of Mars is not only changing the way he sees the universe, but his home planet as well.

Suniti loves the work. But the dreamer sees it as one frame in a much longer film.

"Reflecting on these discoveries and my own journey as a student and scientist only reinforces my determination to explore the planets," he says. "And these discoveries only reinforce my dream that we will one day find extraterrestrial life."

To the skeptics, Suniti insists planetary exploration has tangible benefits, even for those who don’t share his vision.

"Comparisons we make between Mars and the Earth’s geochemistry will lead to new methods to analyze terrestrial data, as well as new insights on the geochemistry of our planet," he explains. "The engineering challenges of such missions will yield applications for Earth satellites, autonomous navigation systems, and maybe even suborbital travel. If we discover present or past life on Mars, it will help us understand how Earth, not Mars, became a veritable Eden."

Ultimately, Suniti sees exploration as both a dream and a responsibility.

"It helps to ponder for a moment that, thanks to the spirit of exploration, many of us can now talk with each other when thousands of miles apart, take literacy for granted, and live to be 80, 90, or older.

"Perhaps one day, the children of our species, on their journeys to distant galaxies, will thank us for keeping the spirit of exploration alive in an otherwise chaotic, ignorant, and violent era."

|