Essential: Reading His Way Through Life |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

"He says that before the program, he couldn’t have traveled from New Mexico to Syracuse," Wedgeworth recalls. "He couldn’t have caught the connecting flight out of Chicago because he couldn’t understand the signs and computer readouts to find his next flight. Embarrassed to ask someone to read for him, he would have turned around and gone home.

"But at his first meeting with us, he said proudly, ‘Today, I read my way from New Mexico to Syracuse via Chicago.’

"He read himself across America, and we read ourselves through life,"Wedgeworth says. "But we underestimate the number of adults in our society who have real difficulties reading and the impact that has on their lives. We underestimate the anxiety they go through. And their numbers are increasing."

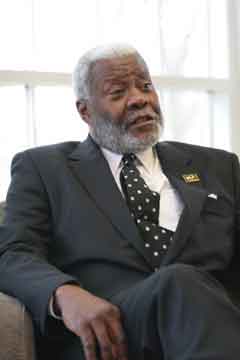

BOB WEDGEWORTH READ HIS WAY to a master’s degree in library services and was dean of the School of Library Services at Columbia University, university librarian and professor at the University of Illinois, and executive director of the American Library Association. But the work he speaks so passionately about today began after he retired from the University of Illinois and soon thereafter took on the presidency of ProLiteracy Worldwide on what was to be a temporary basis.

That was six years ago, and Wedgeworth just announced plans to retire in June.

When it comes to literacy,Wedgeworth is a true believer.

"I understood very early on how important it is to have access to information and knowledge," says Wedgeworth, who attended all-black Lincoln High School in Kansas City, MO, and took his first job in a library when he was 14. "Books have always been an equalizer for me."

He needed that equalizer his first week in a Wabash classroom. It was 1955, the Cold War was raging, and political science professor Phil Wilder was leading a discussion about communism and McCarthyism.

"I didn’t know who Joe McCarthy was,"Wedgeworth recalls. "I was absolutely petrified. I was afraid that Professor Wilder was going to ask me about this. I’d vaguely heard about it, but in the black community we weren’t really that fearful of communism.

"As soon as class was over, I went to the library to read. That ability to read and find information was always my savior."

Today, Wedgeworth works to save others from the shackles of low literacy. ProLiteracy Worldwide works with 1,200 groups in the U.S. and 62 countries providing materials, funding, and reading programs for children and adults. Wedgeworth is the group’s chief spokesperson, a role that put him in the news earlier this year when the results of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that 30 million adults in the U.S. score below basic literacy, with 11 million having no ability to read or write in the English language.

"These figures have huge social and economic implications," Wedgeworth says. "Adults with low literacy rates do not generate significant incomes and they have a higher need for public assistance. They don’t practice the preventive medical care more common among the average family, spend an average of $21,760 per year on medical costs versus the average of $5,440 (usually underwritten by taxpayers), and 70 percent of those in prison have low literacy rates.

"We have too few resources devoted to literacy in the U.S., and we’re failing at the policy level because we haven’t realized that adult literacy is a necessary and worthwhile investment in our people," Wedgeworth says. "In the long run, what’s going to make our society better will be the contributions of our people, and we must invest in people, not things."

Given a blank check, how would Wedgeworth invest it?

"We’d have a coordinated adult literacy program sideby- side with literacy programs for children in every community," Wedgeworth says. "This would have an immediate impact because adults in literacy programs tend to become better workers, better neighbors, and better parents who support their children’s literacy and education.

"And we’d have some form of acculturation for new immigrants, including language and reading.The generation of immigrants that came to the U.S. between 1990 and 2000 was the least well-educated and had the lowest literacy of any 10-year period since we began the census in 1890. There has to be a literacy component to immigration reform."

"Communities engaged in violent struggles all tend to have low literacy rates," Wedgeworth says. "One of the best ways to deal with that strife is by increasing literacy, and especially the literacy of women. Educated women contribute to economic stability and tend to have a moderating influence on violence, because violence threatens families. Where women are least educated, their moderating influence on men is less."

From South Africa to South America,Wedgeworth has seen literacy tear down social barriers and improve lives and communities. He smiles as he recalls a recent trip to Bolivia, where ProLiteracy has a program that pairs women from local Soroptimist service clubs with indigenous Quechua women to teach reading, health, sanitation, and nutrition.

"In one class, the Soroptimists were teaching the Quechua women how they could use some of the local vegetation in the area to improve the nutrition of their families," Wedgeworth says. "When those women got together, there was no class division, no rural or urban difference. They were women talking about things they have in common. And though it doesn’t sound like literacy, when they’re learning about health and nutrition, they’re also learning a basic vocabulary they can build on."

That same trip, Quechua women from 15 of these groups gathered in a village in rural Bolivia to give presentations for Wedgeworth and his colleagues.

"In 30 years of working with students and faculty in the academic world, I never experienced the fulfillment I felt listening to these people talk with such pride about their new literacy skills, how they had improved their lives and the lives of their families,"Wedgeworth says. "No matter how many times I hear it, in English, Spanish, or Quechua, I’ll never tire of hearing it.

"So I may never completely retire." He laughs. "I’m having too much fun!"

WHEN BOB WEDGEWORTH ARRIVED IN CRAWFORDSVILLE IN 1955, all nights at the local skating rink except Mondays were for whites only.Well-paying factory jobs weren’t open to black men or women, and the civil rights laws that prohibited store owners from excluding African Americans were almost a decade away.

"The black community in Crawfordsville was hardly visible,"Wedgeworth recalls. "You didn’t see them shopping downtown; you really didn’t see them on the streets at all."

"As a Wabash student, I was treated differently—I could go pretty much where I wanted in Crawfordsville," he recalls. "But I didn’t see African Americans at the ice cream parlors or restaurants, and when I became aware from friends in the local black community why this was the case, I limited my contacts with downtown.

"The atmosphere there was repressive, in a subtle sense,"Wedgeworth says. "So Wabash became an oasis where I could be treated as an individual."

In fact, during the 1955-56 academic year,Wedgeworth was the only black student at Wabash.

"That made it difficult for people to treat me as a category or a group," Wedgeworth says. "They had to deal with Bob Wedgeworth and all the peculiarities and characteristics unique to me. Being treated as a Wabash man, I matured quickly."

But even at Wabash, fraternities did not admit black students. And the basketball team’s schedule included games in cities where interracial contests were not allowed.

"I knew guys who had played under those conditions, and they had told me what it was like,"Wedgeworth says. "A friend of mine who ran the 400 meters at the Drake Relays told me than when the team stopped for dinner on the way back to his university, his teammates had to bring him dinner on the bus.

"I would have given up basketball rather than suffer that humiliation."

But the schedule was changed and Wedgeworth went on to a Wabash Athletics Hall of Fame career as a Little Giant. He and his basketball teammates grew close and have remained so through the years.

"We were on a road trip to play Washington University in St. Louis when the assistant manager at the hotel where we were staying caught me alone and told me to use the freight elevator,"Wedgeworth recalls. "I went up to Coach Bob Brock’s room and related what had happened. I don’t remember ever seeing him so mad. He went downstairs with me, but the manager hid in his office and would not come out.

"Coach and my teammates were solidly behind me everywhere we went.

"Another African American, Julius Price, came my sophomore year, and I was happy to see him,"Wedgeworth says."We could share things we had in common that I didn’t have in common with the other guys, though our interests and backgrounds were different.

"But that first year was very special."

THEY CAN LOOK RIGHT THROUGH YOU

"My favorite novel at Wabash was Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It opened my eyes to complexities of the black experience I had not completely understood.

"How could someone as physically different as I be invisible? It’s not that people don’t see you physically. But they can look right through you.

"That understanding was an important part of my development at Wabash."

MR. MANNERS

"My mother bought me a copy of Emily Post’s Etiquette when I was in junior high. I laughed, but I read it. The black community in those days put a lot of emphasis on good manners. What I learned from Emily Post was that manners was not about doing things right, but about being at ease and putting others at ease. They were a way to feel comfortable under many different circumstances.

"My parents and my teachers knew I would have to acculturate myself to the world outside the black community. For their generation, good manners was an important part of that acculturation."

|

PROLITERACY WORLDWIDE PRESIDENT AND CEO Bob Wedgeworth tells the story of a New Mexico man who grew up with poor reading skills. After he enrolled in a ProLiteracy program, the man’s life improved so dramatically that he became a member of the advisory board for the Syracuse, New York-based organization.

PROLITERACY WORLDWIDE PRESIDENT AND CEO Bob Wedgeworth tells the story of a New Mexico man who grew up with poor reading skills. After he enrolled in a ProLiteracy program, the man’s life improved so dramatically that he became a member of the advisory board for the Syracuse, New York-based organization. WEDGEWORTH BELIEVES LITERACY is the skill that makes the difference between hope and despair in developing nations.

WEDGEWORTH BELIEVES LITERACY is the skill that makes the difference between hope and despair in developing nations.