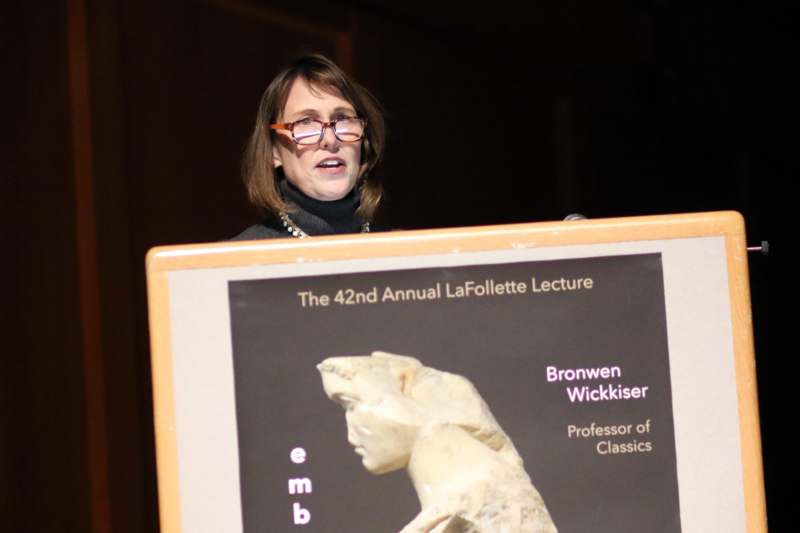

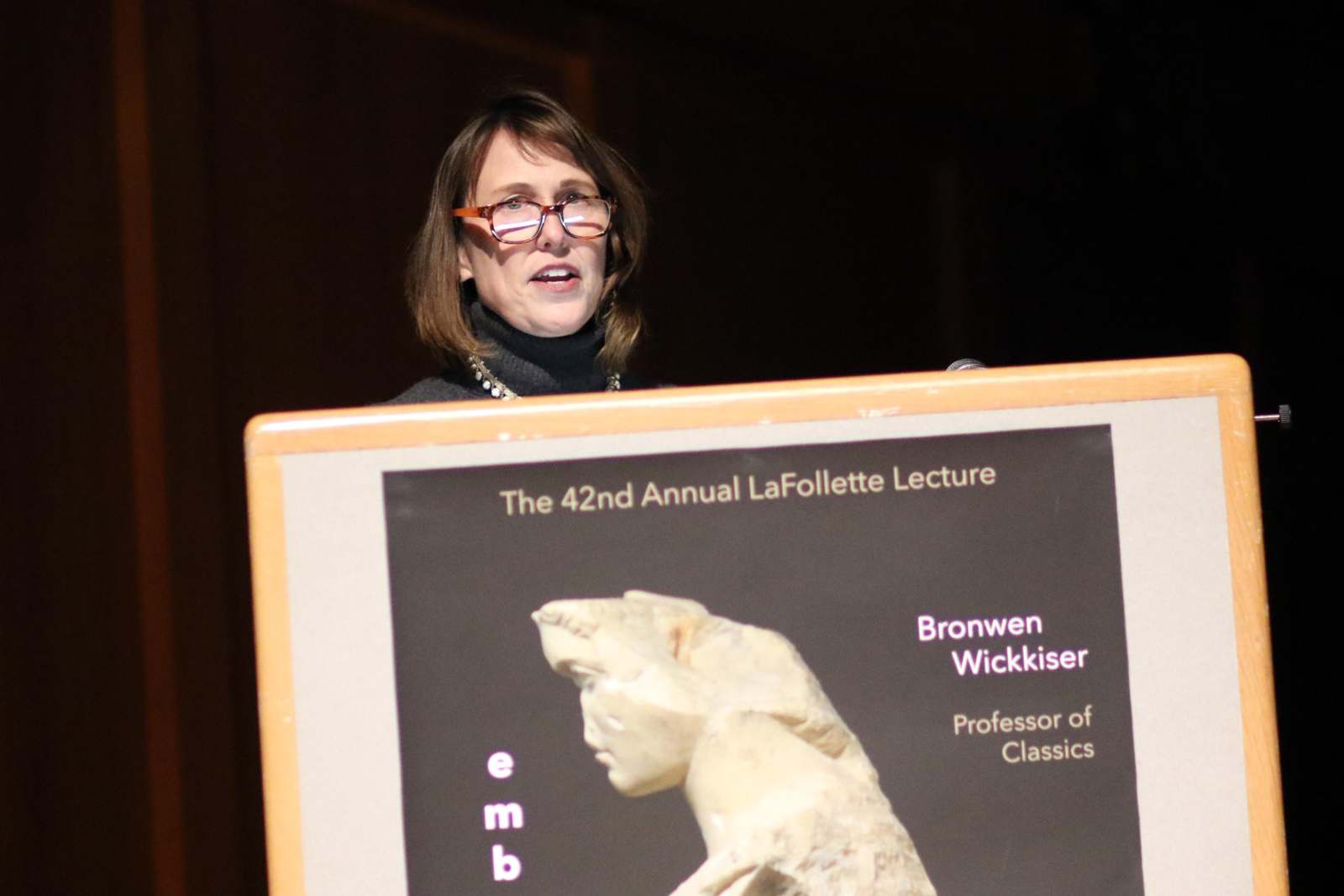

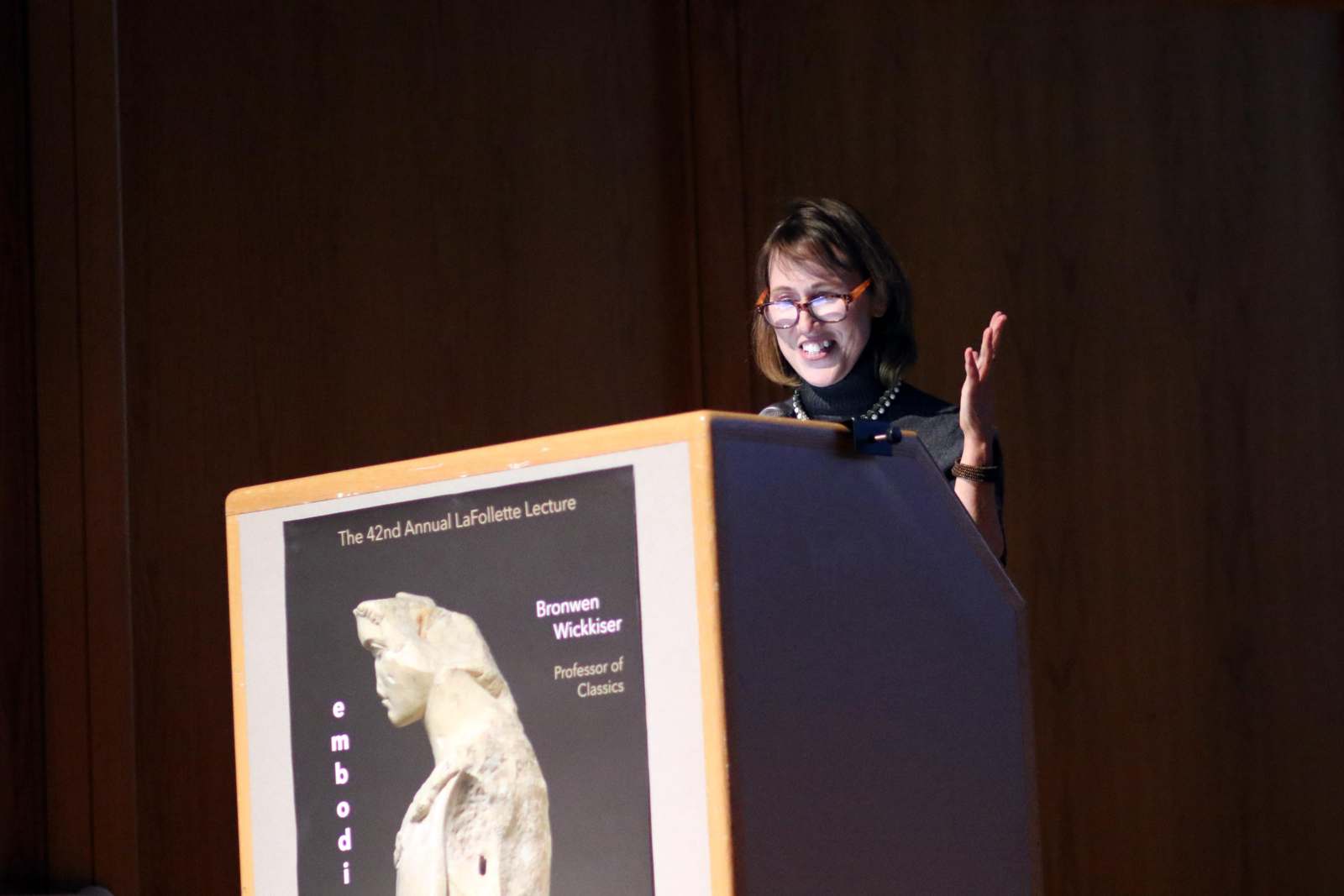

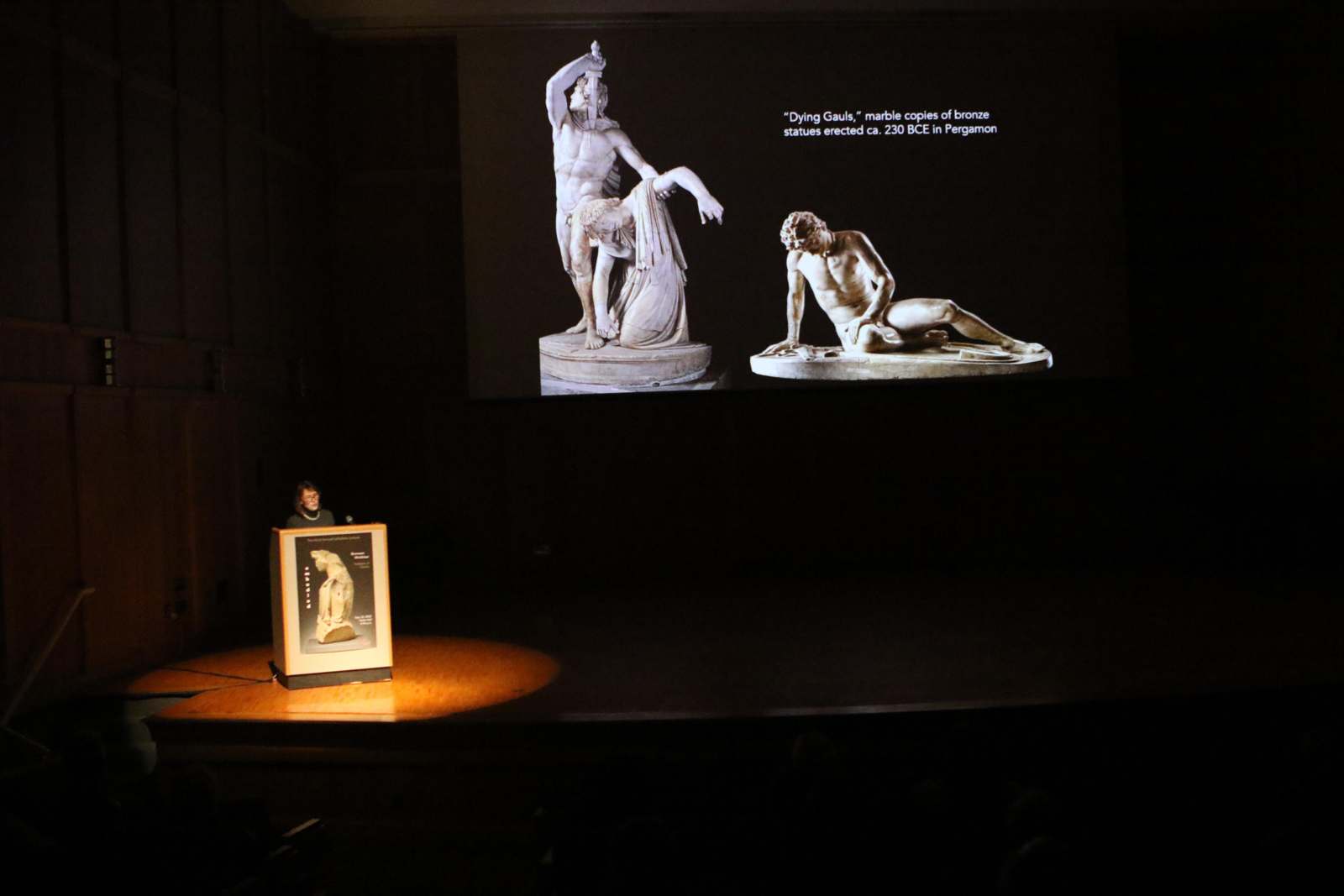

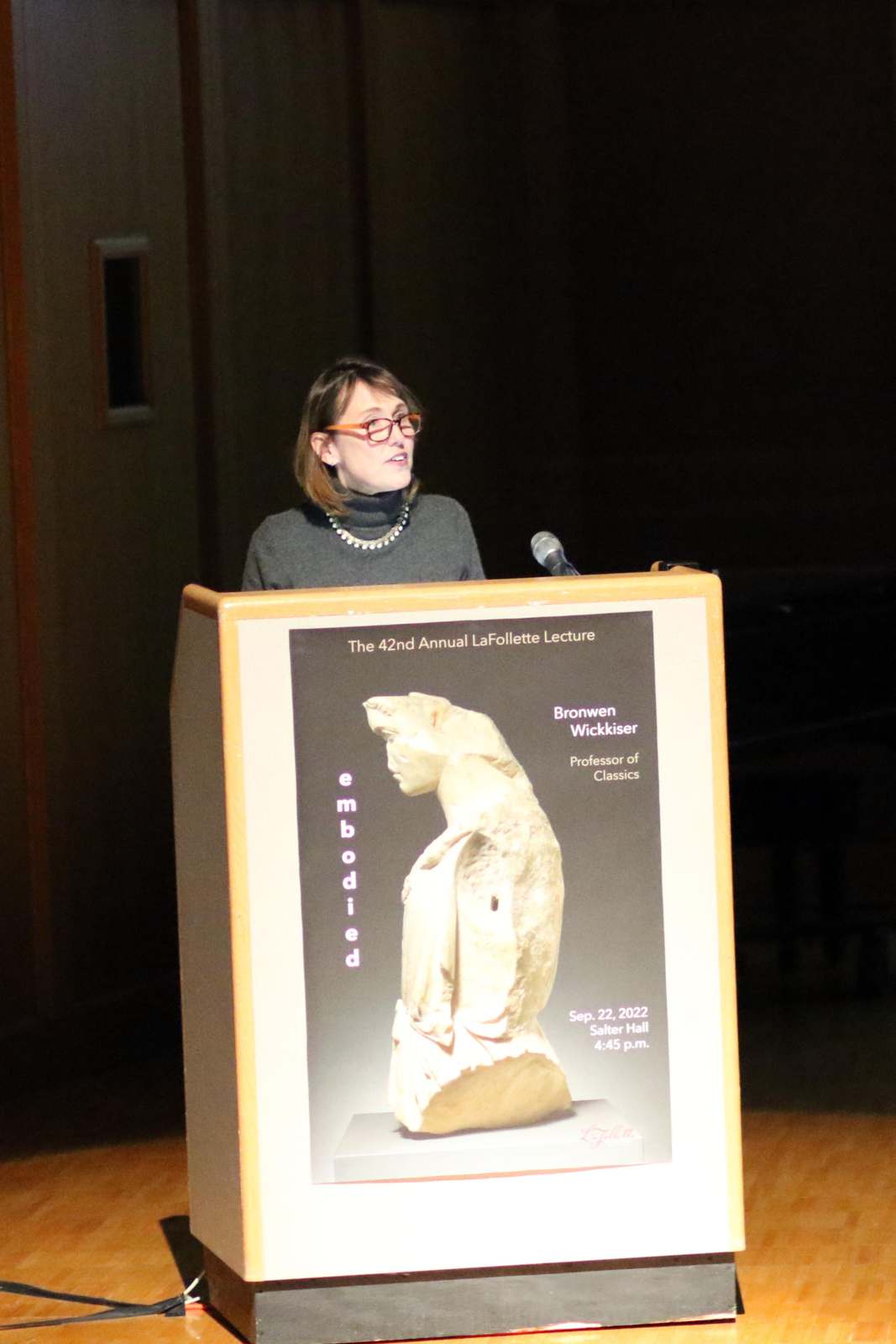

42nd LaFollette Lecture: Bronwen Wickkiser, 9/22/2022

The LaFollette Lecture series was established in 1982 by the Wabash College Board of Trustees to honor Charles D. LaFollette, their longtime colleague on the Board. The lecture is usually given annually by a Wabash College faculty member who is asked to address the relation of their special discipline to the humanities, broadly conceived. This year's lecture, 'Embodied,' was delived by Bronwen Wickkiser, Professor of Classics. Presented with the accompanying photos are excerpts from her lecture.

'Let’s face it: classics is an enigmatic term. classic what? classical music? classic cars? Loosely put, classics as an academic discipline is the study of Greek and Roman antiquity. This encompasses study of two of the languages widely spoken in the ancient Mediterranean (Greek and Latin), the literatures that were produced in these languages, the material remains of the Greeks and Romans, what they did and how they lived. That’s a lot under one umbrella.'

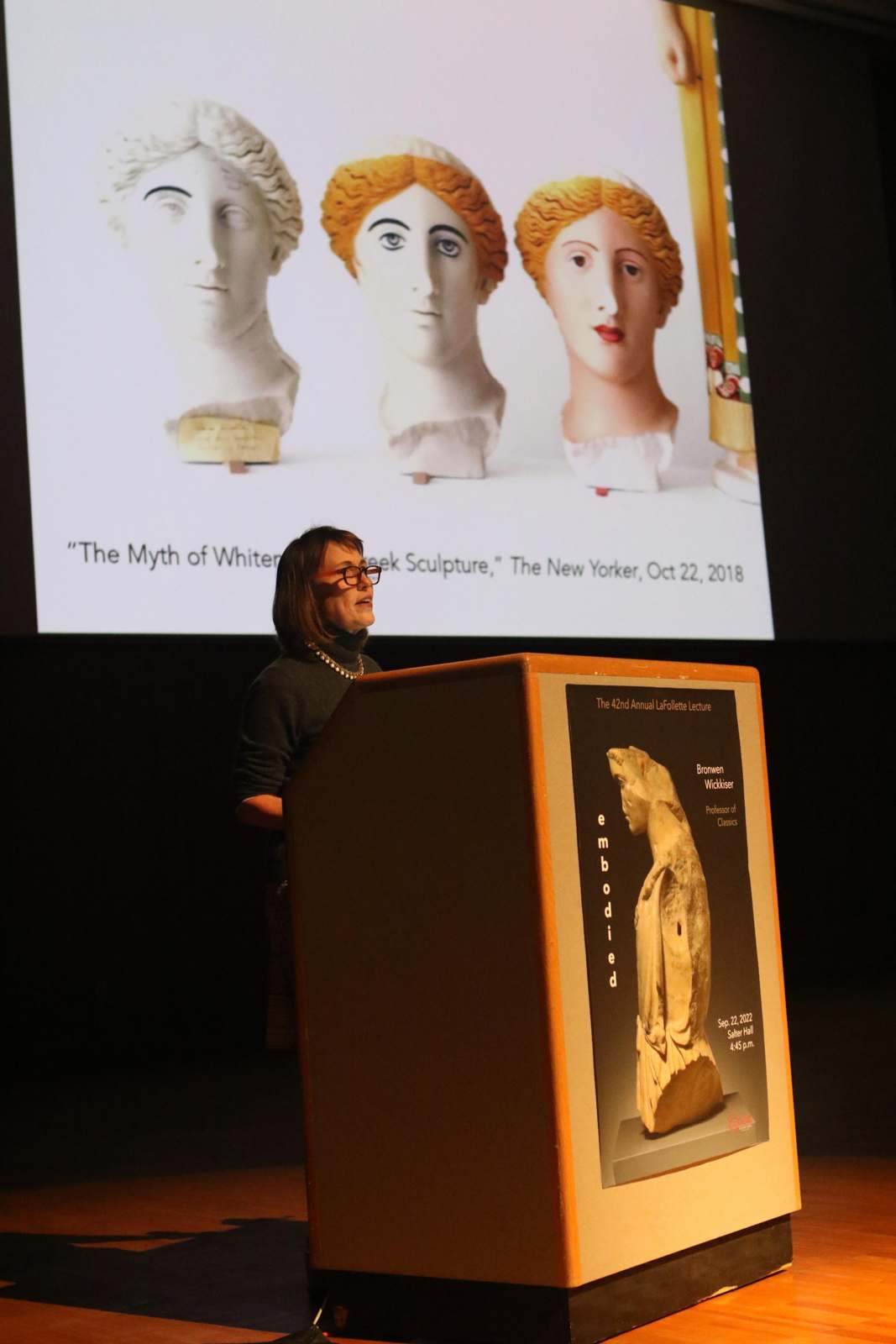

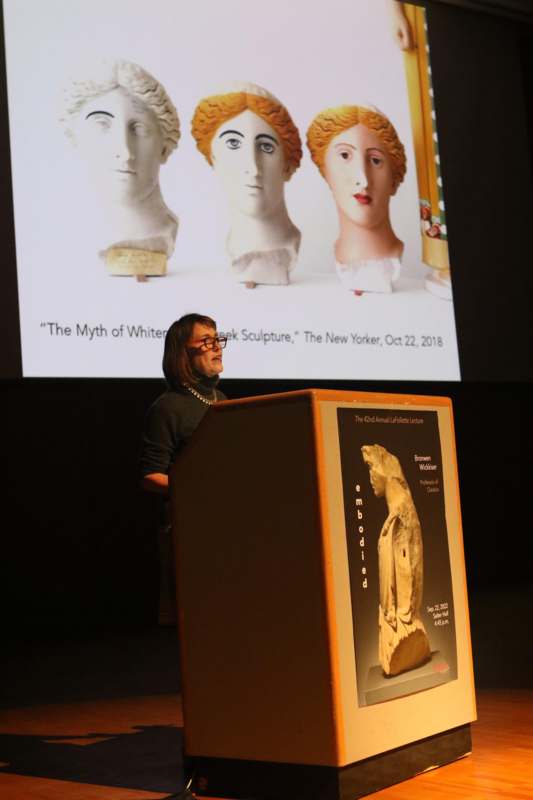

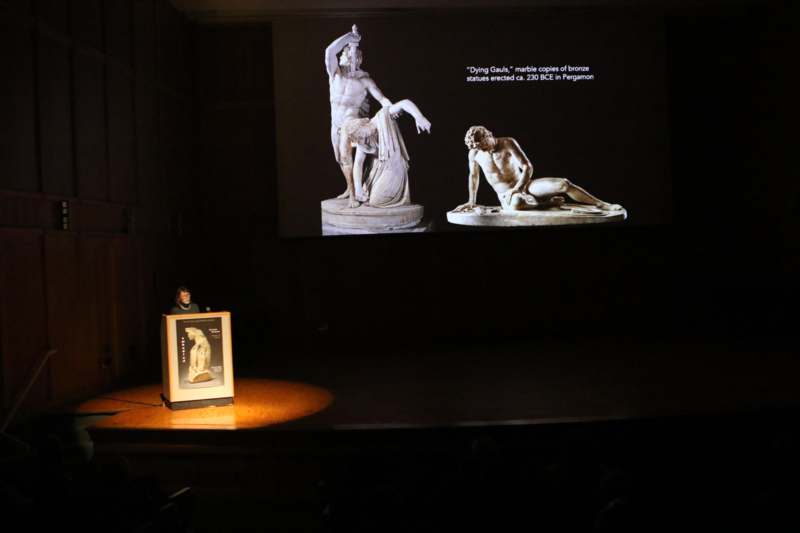

'One of the major challenges of understanding antiquity is the limits of the evidence. I sometimes begin courses with an image... a fragmentary statue of a human figure. I intend this as a metaphor to get at the very incomplete nature of what remains from the ancient past—only a small fraction of all the data of antiquity survives and has been recovered. There is a very real possibility as we work to reconstruct the past—that is, to restore, say, the arm of this statue, or the color of her skin, that we will get some things wrong. Greek and Roman statues would have been bright with color; we know this because traces of paint survive on some of them that suggest that every detail—hair, clothing, jewelry, skin—was painted. Yet for a long time, scholars perpetuated the idea that marble statues and architecture were left unpainted, contributing to a myth of whiteness. This is a good reminder that as we interpret the past, we need to be careful about imposing our own value judgments about aesthetics and race on ancient data, about recreating antiquity as we think it ought to have looked.'

'My course on ancient medicine has become one of my favorite courses to teach. What I enjoy about the history of medicine is seeing the connections—the continuities and discontinuities—over thousands of years about an aspect of human life that is universal: all of us at one time or another get sick, no matter when or where we live, regardless of status, politics, religion. Sickness and health (some combination thereof) is essential to the human condition. And the Greeks and Romans knew this well. Homer’s Iliad, our earliest surviving work of Greek literature, begins with the god Apollo shooting arrows of plague upon the Greek army. As I like to say, Greek literature begins with a disease, and the dis-ease, the unease, that accompanies it: the suffering, the anxiety, the search for causes and solutions. The Greeks and Romans would continue to reflect for centuries on the health of bodies and the body politic in all sorts of literature: works of tragedy, philosophy, histories, and medical texts.'

'I’ve been studying Greek on and off since my senior year of high school: I will remind you that I attended a public high school in Baltimore, moreover, it was and remains to this day all-female: yes, all-female public high schools still exist. I got an education there that I will be forever grateful for, in part because it allowed me to see females in positions of power. It was also where I began to be enamored with classics.'

'If you have the chance to work on an excavation, no matter where, there are few thrills greater than recovering artifacts that have been waiting underground for hundreds, or in the case of antiquity, thousands of years. Even if you do not excavate, just coming into direct physical contact with objects produced in antiquity can be a thrill: I always tell my students: hug a column.'

'My interest in healing cults is driven in part by the materiality of much of the data. Some examples: I study narratives inscribed on large stone blocks that stood in the center of sanctuaries and describe how the gods healed certain individuals; I study body parts sculpted from clay, stone, and metal that were given by the sick as thank offerings for their cures; I examine bronze medical instruments dedicated by physicians to their patron god, and I explore elaborate architecture designed for healing… These I put into conversation with texts like, yes, medical treatises, but also courtroom speeches, hymns, comedies, even a series of short Greek poems about healing that were recovered in Egypt from, I kid you not, mummy cartonnage: papyrus on which the poems were written had been used to cover the chest of a mummy. Poems about healing recovered from mummy cartonnage – talk about embodied!'

'From other sources we know that a major fire ravaged Rome in the year 192, when Galen was in his early 60s. Galen describes this fire. The Great Fire, as he calls it, tore through the center of Rome, beginning at the Temple of Peace, moving through buildings along the via sacra, and climbing the Palatine Hill, where not only the imperial palaces were located but also the Palatine Libraries. Galen does not say whether the palaces were damaged – I don’t think he cares much about them, but he writes at length about extensive damage to the library collections. According to Galen, the fire destroyed important works of philosophy by Plato, Aristotle, and Theophrastus, critical editions of Homer by Alexandrian scholars, along with noted works by orators, doctors, and grammarians. Some of these books existed only at this library – Galen tells us, there were no copies. This was a great loss to Galen, who used the Palatine libraries for research and to make copies of some books for his own use.'

'Galen himself sailed to Lemnos to learn more about how the tablets of Lemnian earth were produced. Here’s what he learned by watching the process: a priestess of Artemis harvested the soil when it was wet with spring water, she formed it into tablets, stamping each of them with an image of a goat, and laid them out in the sun to dry. After this they were ready for distribution. Galen believed so strongly in their therapeutic benefit that he shipped 20,000 tablets of Lemnian earth back to Rome. We might be thinking: what the heck? They used earth as a cure? We still do something like this today. Maybe you’ve heard of Terramycin? In the 1940s the pharmaceutical company Pfizer discovered that soil near one of its laboratories contained antibiotic compounds (Oxytetracycline). They marketed this as Terramycin as early as 1950. The terra of Terramycin means earth, but not just any earth. Pfizer discovered the antibiotic compounds in earth located in Terra Haute, Indiana. That is why it is called TERRAmycin. So there you have it: a close link between Indiana and a small Greek island, between ancient and modern medical practice. You can see by the way, that Terramycin is still used for eye conditions. Oh, humility!'

'Galen does not leave the aversion of disaster entirely in the hands of the gods. He trains his body and mind daily to prepare for misfortune. In addition to regular physical exercise, he engages in a kind of proto cognitive therapy by reminding himself—reciting to himself—a passage from a now-lost tragedy by the poet Euripides. One of the characters in this tragedy says: As I once learned from a wise man, I fell to considering disasters constantly, Adding for myself exile from my native land, Untimely deaths and other ways of misfortune, So that, should I ever suffer any of what I was imagining, It might not gnaw at my soul because it was a new arrival.'

'It’s a little about one text with relevance to us in the 21st century. A text that puts me in Rome, on the via sacra, that puts me in touch, even indirectly, with the stuff of the practice of Greco-Roman medicine. Moreover, it’s a text that I hope demonstrates how the study of healthcare makes for an intimate connection to the distant past.'