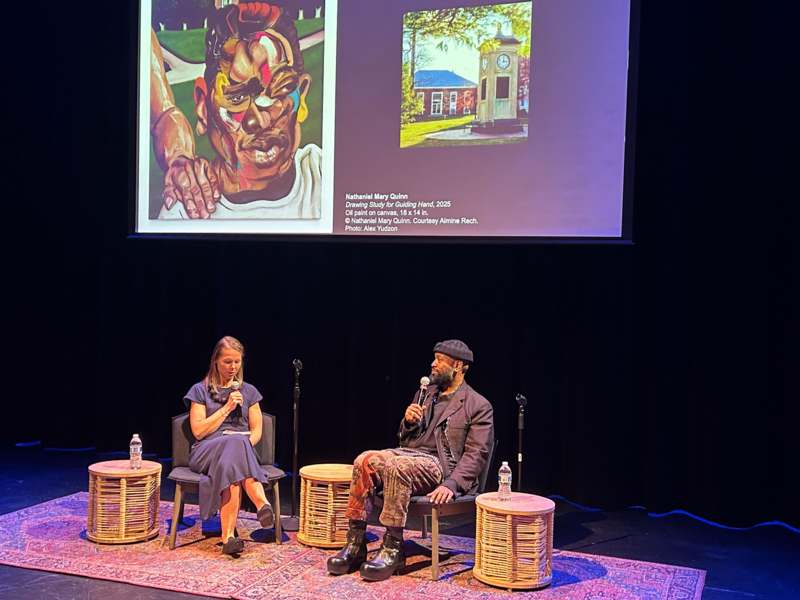

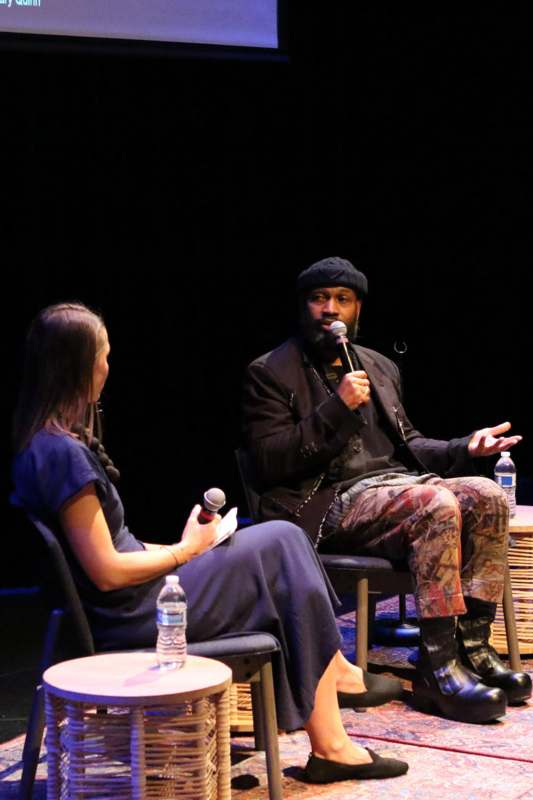

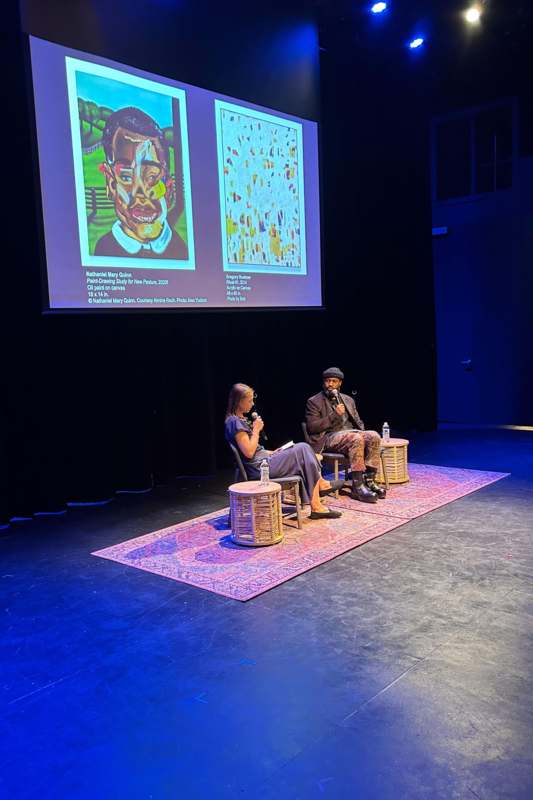

The Hand That Guides: Nathaniel Mary Quinn '00/Greg Huebner H'77 Exhibition Opening

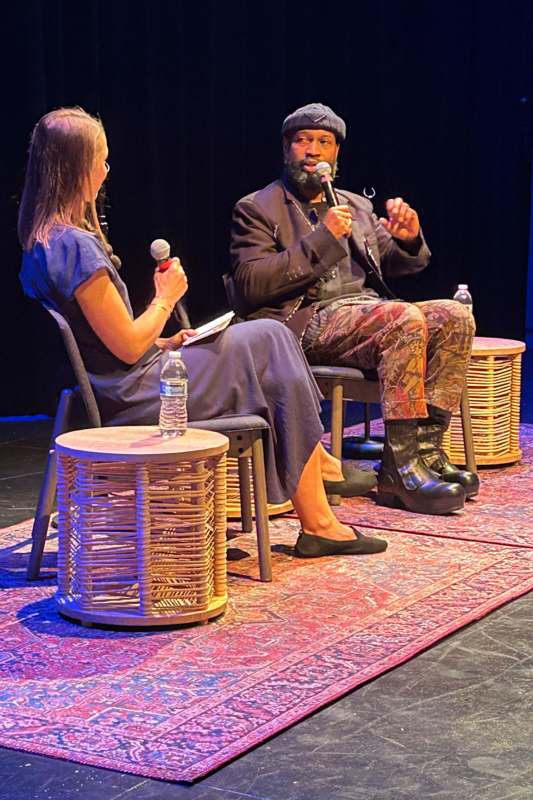

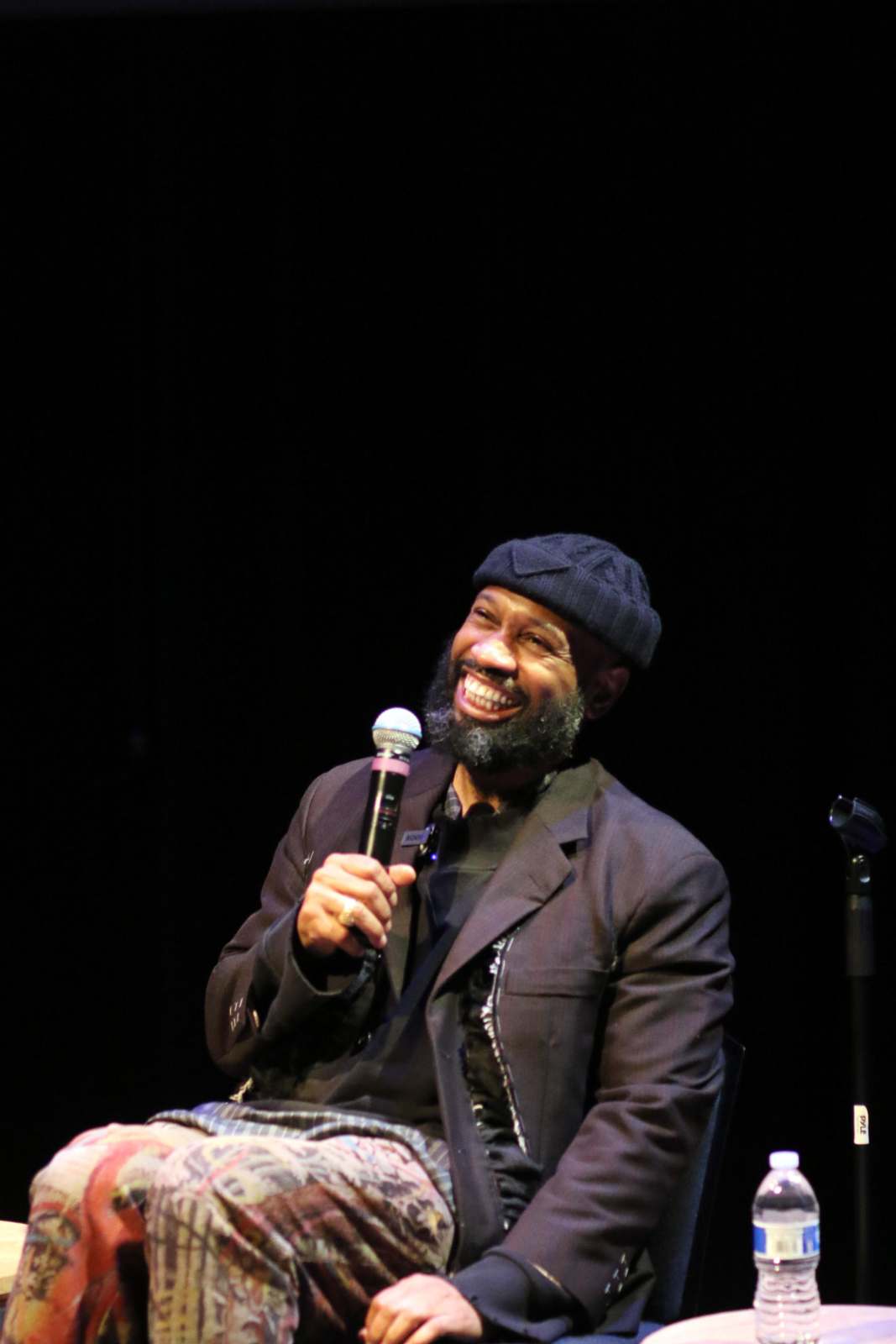

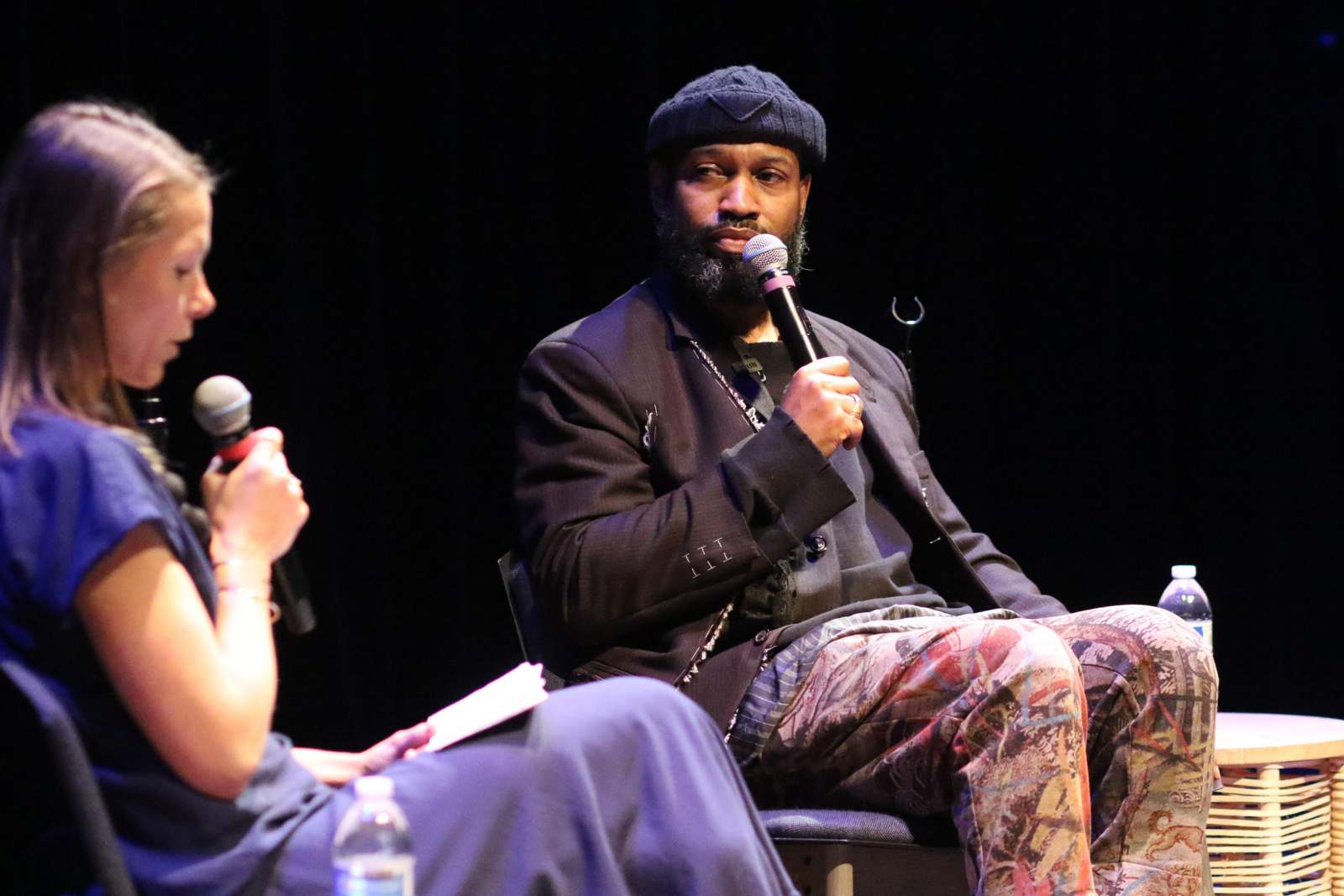

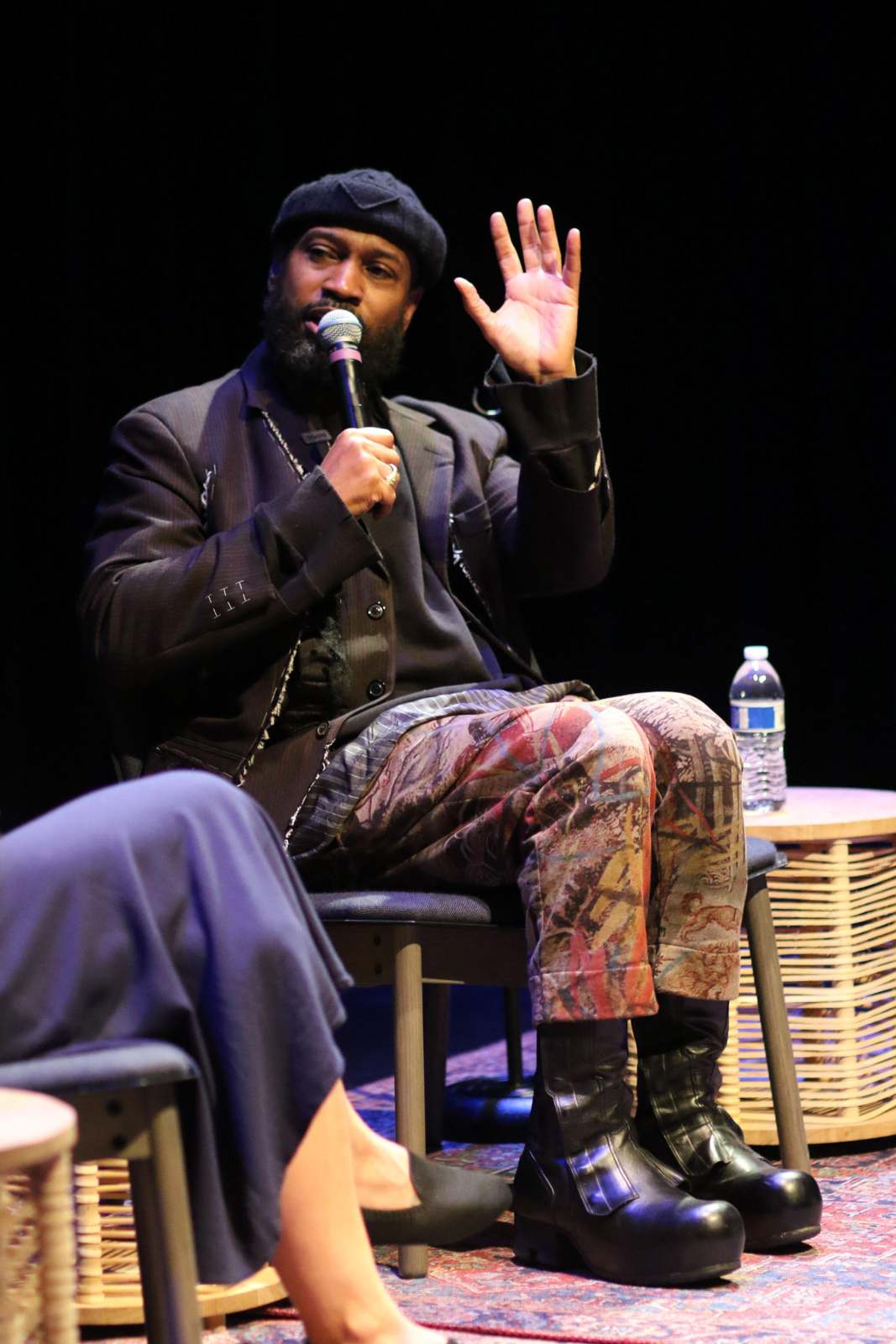

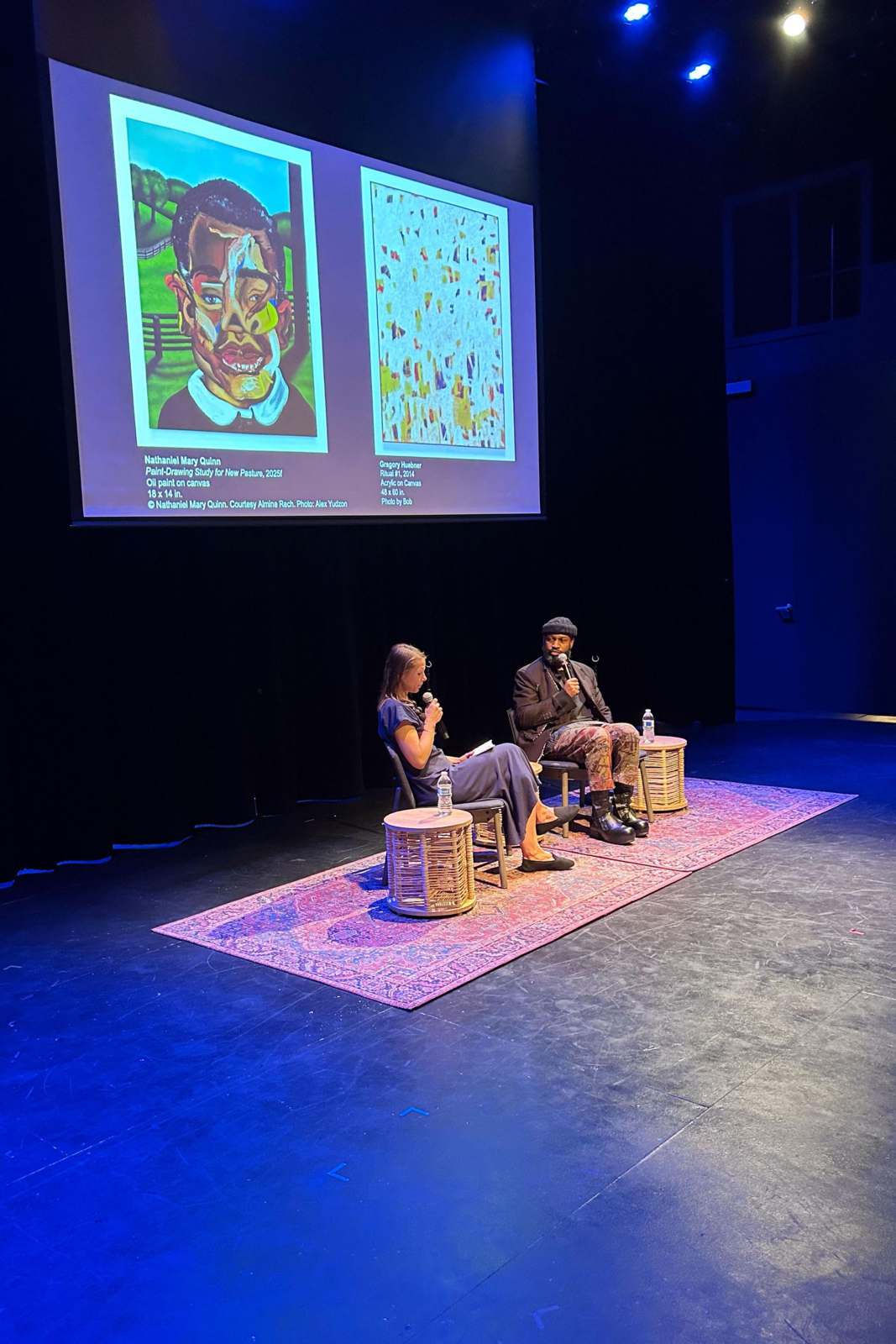

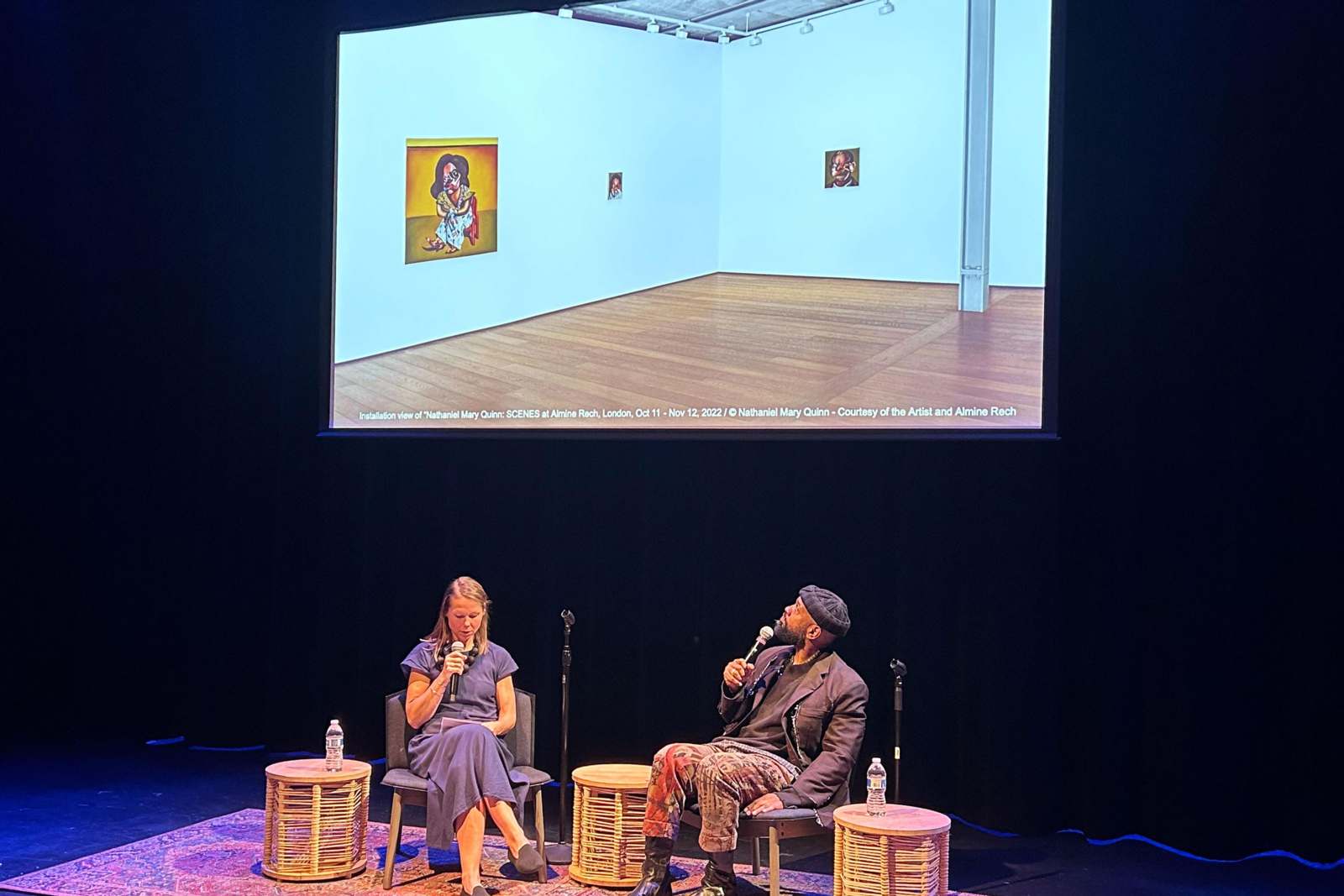

Celebrating the first combined exhibition of Nathaniel Mary Quinn '00 and mentor, friend, and professor Greg Huebner H'77, the duo participated in an artist talk at the Green Line Performing Arts Center, Arts + Public Life’s performance space in Washington Park, followed by a gallery opening at Arts + Public Life’s Arts Incubator. Arts + Public Life is part of UChicago Arts within the Division of the Arts & Humanities.

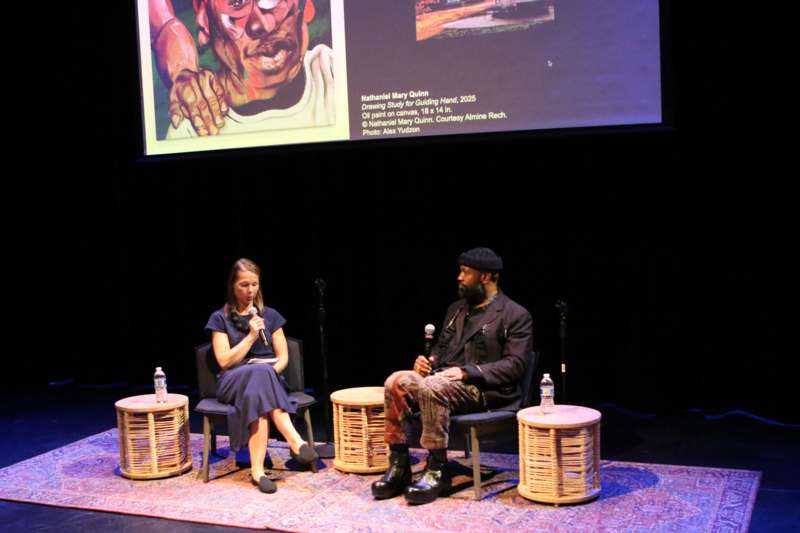

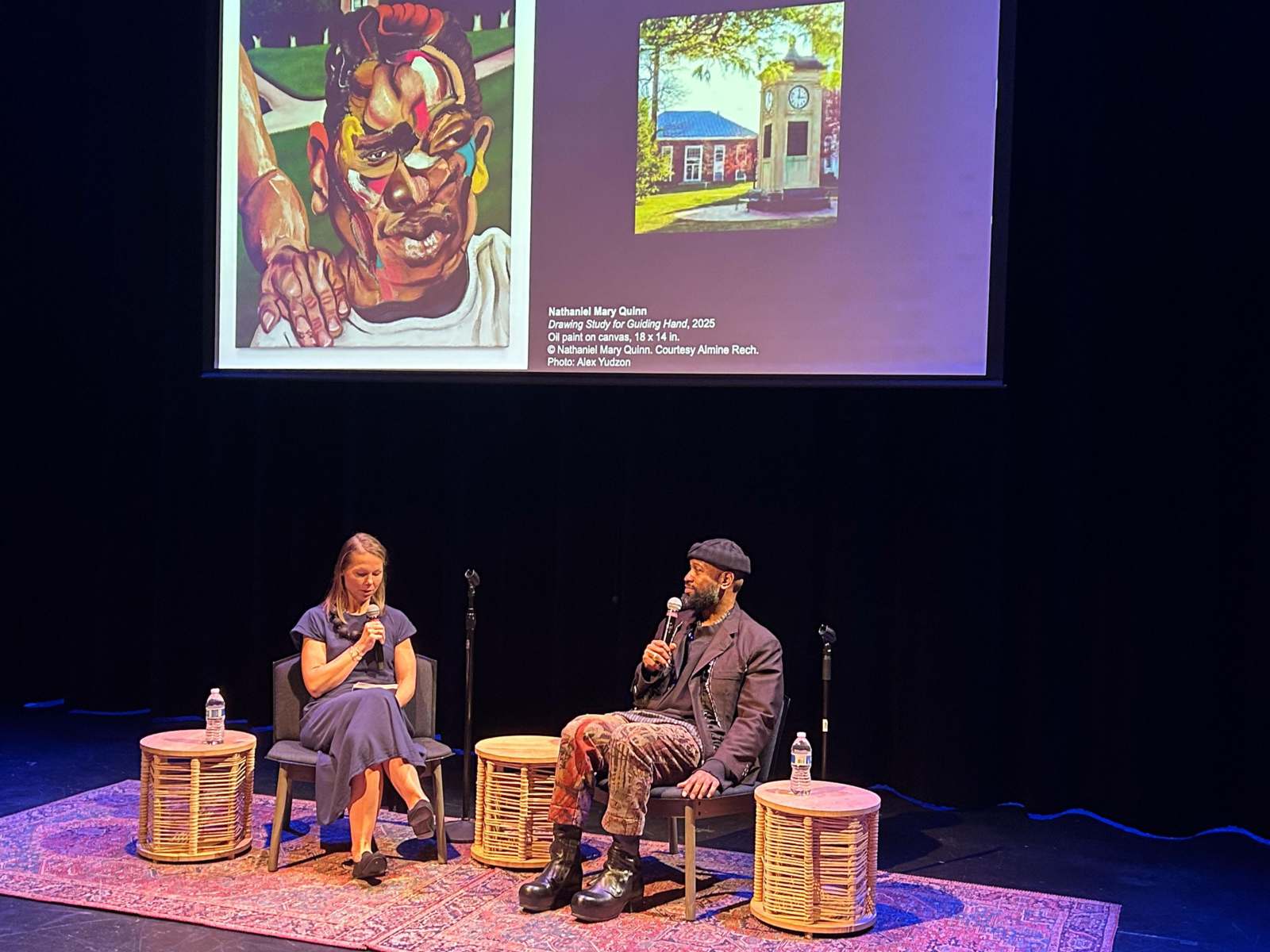

Quinn presented a new series of works for the exhibit that center on the "guiding hands" that have shaped his life and artistic path.

The exhibition also spotlights Huebner's Ritual Series (2015-present), a collection of abstract paintings that channel his lifelong exploration of the unseen.

"I grew up in the Robert Taylor homes, 4500 South State Street, on the sixth floor in apartment 604. I was the youngest of five boys, so I had four older brothers, mom and dad," Quinn started. "My mother was crippled from two strokes. Both of my parents could not read or write, and we were poor, but that was commonplace in that community, all of the families there were poor, working class people... It was a very tough upbringing. It was very challenging. I oftentimes say that the Robert Taylor Homes were most efficient at killing dreams. That's the best way for me to describe that community that does not exist today. At the time, that community was quite reverent in its ability to kill one's prospects of an optimistic future."

"When I turned 15, I had the privilege of attending the Culver Academies in Indiana," Quinn said. "A month after being admitted, my mom passed away, I returned to Chicago to attend the service. I bear witness to my mother in the casket. I touch her forehead; head was cold; it was a shocking thing for me to experience. I returned to Culver and two months later, I would come back to Chicago for Thanksgiving Break, and I walked into an apartment that was entirely empty. Everything was gone, including my father and my four older brothers, and from that point on, I no longer had contact with my family. (Culver Academies teachers) Ms. Pilcher and Ms. Jackson took me under their wings, and they provided me with support and refuge, and they encouraged me to keep moving forward. Going to school at Culver became a binary pursuit. On one hand, I was in pursuit of academic excellence, but on the other hand, the tuition-waiver scholarship allowed me a place to stay, food to eat, and clothes on my back. This school became a mode of survival. My academic achievement was directly correlated with my means of survival."

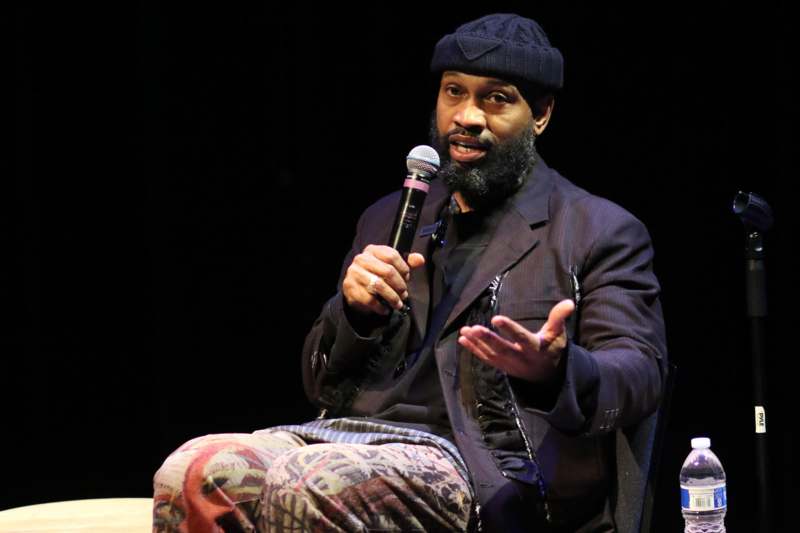

"Greg and I, we've maintained contact over the years, sometimes loosely, sometimes tightly, but Greg kept in touch with me, or he followed me somehow," Quinn said. "I could never forget Gregory Huebner. Greg and I spent a lot of time together talking about art. Greg educated me a lot in the art world and art institutions. He introduced me to the works of Romare Bearden and other painters, and we talked a lot about drawing and color theory. Greg is an abstract painter, and he knows a lot about color. He stressed a great deal about work ethic, hard work, and being consistent. I looked up to Greg as a man. He's a married man, he's a father, and I really admired the way he moved and carried himself. He's a great writer. He's fun. He has a great sense of humor. He's quite funny. Greg was highly influential for me, no doubt about it."

Tinari shared words from Huebner, sayig, "I recognized Nate's talents immediately. He always had technical skills from an early age, Nate developed fantastic drawing skills, and by the time he came to Wabash, he really only needed to concentrate on developing composition. So my biggest contribution to him, I would say, was teaching him how to focus on his abilities to be a great artist." Further, she conveyed from Huebner, "I never had such a committed student as Nate Quinn. You were always in the studio by eight in the morning and back in the studio every hour that you were not in other classes."

After graduating from Wabash in 2000, Quinn was close to finisihing an MFA at New York University, and was entertaining the idea of pursuing a Ph.D.

"Somehow, I told Greg about this, and Greg flew from Indiana to New York, and he took me to a bar in Manhattan off Canal Street," Quinn explained. "We had Red Stripe beer together, and he sat me down, and he says, 'Nate, you are a very smart guy. You will excel in this Ph.D. program. I have no doubt about that, but if you go into this program, it's going to really kill your art practice. You will never have time to make art. In all of my years of teaching, you're the only student I have ever come across who had the highest possibility of making it as a full-time artist. Don't do this. You really have what it takes to become a full-time artist, just don't go to this program.'"

"I'm very happy that I listened to Greg," he continued. "It wasn't so much the words coming out of his mouth, it was the conviction with which he spoke. I could not deny the fact that this man got on a plane to fly to New York to specifically tell me that it meant a lot for him to tell me this. And I listened."

"Greg gave me this, like, profound wake up call," Quinn said. "It's like he was the embodiment of God. And I said, 'Yes, I will do it.' And that was it. Okay, that's it. This man believes in me. I trust everything coming out of his mouth. I've always trusted Greg. I look up to him, respect him with every fiber in my being. He's never led me wrong. That was it, and you could not tell me different..."

"(For a period thereafter) I worked with at risk youth, and I wanted to make sure I had time every day to go to the second bedroom of our two bedroom apartment and just make art," he continued. "And I did that every day, two hours a night, every night for 10 years, and I was happy doing that, because, you have to understand, I had a job. I was teaching those young people. I was an adjunct professor. I did one-on-one tutoring on on the weekends."

(on his breakthrough moment in 2013) "I had four paintings already, but I needed to make a fifth work, but I didn't have a lot of time, so the fifth work was drawing on paper," Quinn explained. "I mean, drawing is my primary strength, and that's when I made the work "Charles," which introduced this new visual language that is now a staple of my art practice. And everyone gravitated towards that piece. And it was very exciting for me."

Tinari followed, "It's so interesting. I heard someone say that when you squeeze an orange, you get orange juice. And sometimes when you're squeezed, there's some, you know, there's something within you that comes out, and you were under pressure and you didn't have a lot of time...your unique kind of piecing together, the synthesis of these figures and portraits came from a very internal place."

..."and also my mother's physical body, because she was crippled," he continued. "So as a child, her body became the example of the perfect body, because that's the first body I adored. She was my mom. That's why, I guess subconsciously, I make my faces and figures in that way. You know, I'm constantly making reflections of my mother's physical body, and to me, that's very beautiful, because my mother is a beautiful woman. I'm always trying to revisit that constantly through my art practice."

"When I was, I think, still crawling, but I was drawing on the walls all the time, and my mom would spank me and discourage me from scuffing up the walls," Quinn said. "And then, of course, there I go again. And my brother stopped and said, 'Wait, mom, look. Look at the drawing.' And then for the first time, she recognized that the drawing was actually quite good. And then she would let me draw. The walls of the apartment and the projects was my first drawing pad, and she would let me draw on the walls, and then she would wash the walls down so I can do it again."

"My dad, found this old, raggedy table, and he brought it up to the apartment, cleared out the pantry, and he turned that into my studio," Quinn said. "And he says, 'You draw here every weekend after you do your homework, and that's it.' He would take shopping bags from this grocery store that was called Super Jet on the south side of Chicago here, and he would take the grocery bags and rip them up. And I would draw on the bags..."

..."and he would like rip off the erasers on a pencil, because he says, 'You will never erase. You know, every mark you make, you will make it with purpose. If you make a mistake, you'll find a way to resolve that mistake.' And he told me to draw with my entire arm instead of just working from my wrist. He said, 'your arm is your tool, not just your wrist.'"

Tinari made a connection between Quinn's and Huebner's approaches to art, saying, "You were always making art. Before you could walk, you were drawing. Gregory Huebner always recalls making as well. His high school didn't have art classes, so he would come down to the School of the Art Institute and take summer classes. And then he signed up for night classes in his local art school from 8 to 11 p.m. and he was the only kid in there. It was mostly older adults, but he was sometimes too tired to drive home. Yet he found a way to make art."

Tinari said of Huebner's work, "I was really struck by these early paintings called the Amplexo series, in which Greg was folding up -- these are large scale canvases -- and he was folding them up and letting the canvas form these creases, and then airbrushing them with layers of paint, and so they really shimmer in person. And I love that he kind of found a way to make these paintings that were within that language of color field painting, but they're just really beautiful and subtle."

Tinari once again relayed Huebner's words, "My canvas is a stage upon which my actors color, line, texture, shape, space, and gesture act without a script, constantly improvising with each other until the second act, when the director, who would be me, directs them into relationships that begin to reveal clarity and focus for the common good."

Said Quinn of Huebner, "He taught us everything.The art department at Wabash is very special because they provide the art students all the materials. You didn't have to buy any art materials there, and it was all provided by the college, by the department. Greg taught us how to stretch canvases, how to build the bars, how to lay down gesso, how to make sure it was tight, and how to use the different tools. Truly, he's a real practitioner of the arts, and he cares about art. I mean, really loves art. It was not just a job for him, like he really cares about the art making process, and he cares about the students' work, and he believed in you. It was palpable."

On the discipline he learned of being an artist from Huebner, Quinn said, "Simply working every day and pushing yourself every day and being consistent and being on time and being very disciplined. I imagine there were some days where I was like, 'Oh man, I don't want to go to the studio. Boy, oh boy, but I will go anyway, you know.' But for the most part, I looked forward to going to the studio. A big part of my motivation was to impress Greg. I wanted him to be proud of me, because I looked up to him."

"He (Huebner) was a tough critic," Quinn said. "He was honest, so he taught me how to have thick skin. Well, I'm malleable in that way. I don't have a problem taking criticism, because I always feel that criticism is designed to make me better, and I will not dare get in my own way by refusing to listen. Simply put, being disciplined and persistent and doing it every day, yeah, without excuse."

"I saw both (Francis Bacon) exhibitions in London (in 2022)," Quinn said. "I saw the first one at the Royal Academy of Arts, and then I went back to London again, and I saw the other Francis Bacon exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Both shows blew me away. The one at the Royal Academy of Arts, I walked through that show and shed tears."

"Seeing those paintings helped me to resolve issues that I was contending with in my own studio practice, and the experience of seeing those shows completely shifted the way, or it changed the lens through which I was seeing my own practice, and I used those solutions and incorporate them into my own work," Quinn said.

"The placement of the figure in the space, the use of architecture, the fluidity of the figures, the momentum in the bodies of the figures, and the activity of the paint, the introduction of different kinds of colors that I did not normally use, just a freedom in it," he explained of Bacon. "And the freedom was the main thing. I felt a kinship with this Irish born, British raised man, and that that changed everything for me, in many respects."

On his most recent solo show that closed earlier in October in New York City, Quinn said, "I had a debilitating anxiety about this show. I was really afraid because I had not had a solo show in New York in quite some time. It was my first major solo show in Chelsea, and it was at Gagosian in September, the top of the art season. I was like, 'Oh my God, this is it. This is the fall. I'm going to collapse. It's all gonna be over...11-year run was sweet, and that's the end of that.' I was determined to muster all the strength within me to produce the best works I can possibly produce and I wanted to find a more effective way of creating a marriage between figuration and abstraction. I wanted to find ways of embedding the figures in spaces, both internal and external, but I wanted to do in a way that was organic for me."

"I felt the need to move on from what I had been doing," he said. "Then I started thinking about literature. And I was reminded of a book I read several years ago by Alice Walker called 'The Third Life of Grange Copeland.' When I was an at-risk youth working with at-risk youth, I came across this book, and I read it twice, and it has stayed with me ever since. So there I was again, reviewing this book, and I thought this book will function as the inspiration for this body of work, and I will re-read this novel, this great American novel by, in my opinion, one of the best writers to ever walk the face of the earth. Her first novel published in 1970 and through the investigation of her glorious writing, visions will come to me, and those visions will become the paintings for the show."

Quinn discussed some of the motivations behind the works in this exhibition, saying, "I was preparing for my senior show. It's a big deal at the time, right? Big senior show, and that's that. It was winter break and many students were able to leave and go home to their families. Of course, I didn't have a family to go home to, so I was on this campus, which was sort of barren, and I was alone, but I was working on the paintings for my senior show. I remember I was, in fact, working on a painting that was like a portrait of my mom, and she had her hand on her hip with the red dress. Yes, that was the painting I was working on at the time. I remember this unwavering focus I had. And the focus was a combination of trying not to get lost in the abyss of my family abandonment and trying to avoid falling into a pit of sadness because I really was on the campus by myself."

"When I finish a body of work, I take a break and in the first few days I'm like y'all, this is great. I walk around, go outside; by day three, I think there's nothing else that intrigues me, nothing," Quinn said. "My studio experience is akin to what it would be like for you all to have a vacation on the Amalfi Coast. You have to go there. I'm there every day."

"My wife is my muse," he said. "My studio is where we live in our brownstone. My studio's on the top floor of the brownstone, and knowing that I'm able to provide for my wife a life that's lovely and see her walk through the house, and I'm doing it through my art practice. I'm doing it for her when she has to travel and she's not there. The energy is different. I feel it and I have to do an incredible amount of restructuring in my spirit so that I can continue working, because I must work. I must create art."

"There really is nothing else that I ever wanted to do," Quinn said. "For most of my life, I was making art for free, with happiness and glee without complaint and I still have the same motivation. I want to make the best works of art that I can possibly muster. That's how I approach every piece that I make, every single work. There is no mediocrity in my work, none. There's no scaling back."

"I am really trying to make the greatest work of art of all time, every time," Quinn explained. "Every single stroke is driven with that specific intention. Because the more I sharpen my skill set, the more effective I become in expressing myself. But that requires tremendous work and hours of labor. It must be done in order to express whatever it is I'm trying to express. I'm trying to figure that out in many cases.You just have to be present."

"I think painting, in particular, what Greg and I do, is the closest we come to understanding the disposition of God," said Quinn. "That's how powerful painting is to me. There's nothing, no other mode of art that's more prominent, more beautiful, more sublime, than painting. When you look at a painting, you are looking at marks made by the hand of the artist...immediately, right there. That would be the equivalent of taking a slice of Denzel Washington's flesh and putting it on canvas. But when you watch a movie with Denzel Washington, there's so much distance between you and Denzel. First, it starts with him on the set, you have the camera, then the editing, then the recording, duplication, the movie, and then streaming. See all the distance that's there? With painting, that doesn't exist. When you look at a Picasso, you're looking one step removed from Picasso himself. That's how powerful painting is to me, and I feel that in my practice."