For three recent Wabash graduates who followed different paths through college, Teach for America landed them all in the same place—at the head of the classroom.

Here are many ways one can enter the teaching profession without an undergraduate degree in education, including the popular Teach for America program, which continues to attract some of Wabash’s best and brightest graduates. Applicants commit to two years of teaching in high-need areas. In exchange, they go through a rigorous five-week training program over the summer, are guided by mentors, and take master’s-level coursework.

Stephen Batchelder ’15, Arion Clanton ’15, and Donavan White ’12 cite different motivations for applying to TFA. For Batchelder, it was the opportunity to work in a district similar to the Title I schools he attended—a calling, “to make an impact in the lives of others,” he says.

Clanton wanted to be an athletic director, and still may be someday. He recalls in a seminar class as a freshman, then Associate Professor of English Jill Lamberton told him regularly that he was going to teach one day.

Clanton wanted to be an athletic director, and still may be someday. He recalls in a seminar class as a freshman, then Associate Professor of English Jill Lamberton told him regularly that he was going to teach one day.

“I don't know what she saw in me, but I was not going to be a teacher.” Three years later he realized Lamberton might be onto something. He applied to TFA to see what doors opened for him.

White was a political science major who planned to become a lawyer. No matter which cases he studied in Constitutional Law, he found himself mentally siding with the little guys.

“All these cases kept going against the people who I felt needed the most help,” says the former four-year member of the Little Giant track and field program. “I had great interest in the law, but when I started to think about what I’m really passionate about, running, coaching, and young people kept popping into my head.”

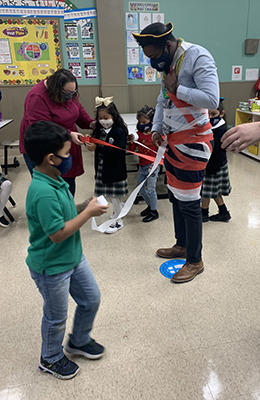

Batchelder teaches middle school science at Estrella Vista STEM Academy in Avondale, Arizona. Clanton taught for four years and is now the assistant director of academics at Invent Learning Hub in Indianapolis. White returned to his hometown and teaches algebra at the Ben Davis Ninth Grade Center in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Clanton’s initial training was for teaching second grade. However, he was placed in a middle school teaching humanities.

The brand-new teacher adjusted on the fly.

“You have to take a step back and figure out what are the most important takeaways,” Clanton says. “Fortunately, I had mentors and teachers on-site willing to help.”

Clanton likened his first day to preparing for a football game or track meet—“it was the longest, quickest day of my life”—and getting home at the end of the day with his body aching.

Clanton misses those moments in the classroom, and the academic gains that went hand in hand. Those moments helped him envision a bigger picture.

“When you teach a lesson, you see how it affects the kids,” he says, “like you could jump up and down with them in the moment they get it.

“I just wanted to figure out how to take what I knew from the classroom and be able to make an impact on our entire school,” he says. “In my fourth year of teaching, I had the opportunity to be a mentor to other teachers. I thought, ‘I can step up and lead on a bigger level.’

“There aren’t a lot of men in education,” he says, “and there aren’t a lot of Black men in education on top of that. I went into leadership, so my students, especially my Black students, could see it’s okay to be smart, and not just tough.”

Batchelder, an English and religion double-major at Wabash, sometimes wonders how he was placed in a middle school science classroom. He realized he was able to synthesize what he learned in his English classes and transfer the fundamentals to his students.“

Teaching science at the middle school level is teaching a different style of literacy,” he says. “As an English major I learned how to analyze texts and really understand how language can be used. In the same aspect, a middle school science classroom is much more about teaching students the language of science and how science is conducted.”

Batchelder admits there was more than a little bit of acting going on those first few days. “Fake it ’til you make it,” he says.

Batchelder admits there was more than a little bit of acting going on those first few days. “Fake it ’til you make it,” he says.

“You learn to go forward and present yourself as the most confident version of yourself,” he says. “It was a matter of allowing myself room to grow. I didn’t have to be the teacher that I envisioned myself being on day one, but I can work towards that every day. I can learn something new each day, and that helps me get there. Six years in, I’m still working toward that.”

Batchelder has been struck by the grace his students have shown each other and him, especially in the current uncertain circumstances.

“This year, teaching in a virtual classroom, every day is a new experience,” he says. “I have made myriad mistakes and I always apologize to my students. But they are quick to say, ‘It’s okay, we’re in this with you.’ The grace they demonstrate is so, so pure, and something I feel like in the adult world we sometimes completely miss.”

White remembers being nervous at first. But as an Indianapolis native, he was fortunate to be placed in a school on the west side of the city. He was comfortable in the environment and knew what he was walking into.

As an algebra teacher, White is keen to the fact that his subject can be intimidating. But he never stops trying to reach his students, provide support, and help them find the confidence to try.

“I like to see them click with the material,” White says. “That’s one of the best feelings in the world. And when they get it, I’m just praying that they get it the next day, too.”

He believes in his students and wants them to believe in themselves. He knows when the breakthroughs are coming. There is a subtle change in demeanor from sitting at a desk scratching their heads, to picking up the pencil, and raising a hand. Even in a virtual setting, when his students ask him to share problems so the class can work them through together, he knows the aha moments aren’t far behind.

White appreciates the conversations, the give-and-take that leads to student growth, a personal best on the track, or even graduation. A lot of time goes into changing a mindset, sometimes one student at a time. In the nine years he’s been a teacher, he’s never lost sight of the effort that takes.

“I’m meant to be a teacher, that’s my purpose,” White says. “That feeling has never left me. My mission is here on the west side of Indianapolis in the community where I was raised. Every time my kids go on to graduate, I remember our conversations and it reaffirms the feeling that I'm meant to be a teacher.”