My home growing up was next door to the school where my grandfather attended in Mississippi.

Granddaddy Sterling had a stroke before I was born and was bedridden, and it was my task to pick up a tray of food from the school cafeteria for him and Grandmama Jennie every school day. They lived just across the street, so I would walk. If there was bad weather, one of the teachers or sometimes even the principal would drive me over.

Even at a young age, I was learning the importance of legacy and how to honor it.

I grew up with 24 aunts and uncles, so most of my friends were my sisters, my brothers, and my cousins. We were Granddaddy Sterling’s legacy. I can still remember my parents and my aunts and uncles bragging on all of us cousins. That was a legacy I knew I wanted to continue someday.

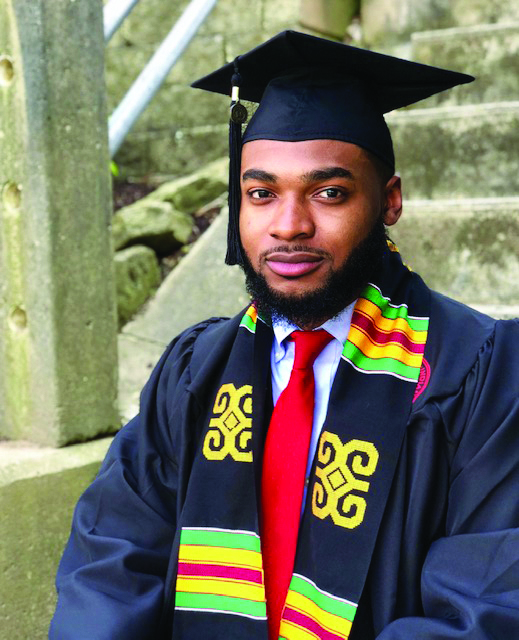

I met my husband, Henry “Hank” Hunt, in Tacoma, Washington, where we were stationed for Army active duty. Together, we have two beautiful children—Dominique and Henry ’18.

Because of the love I had always been surrounded with, I wasn’t afraid to bring children into this world. Hank and I believe in the power of prayer, and I think you have to have something you believe in to keep yourself from going crazy.

Because of the love I had always been surrounded with, I wasn’t afraid to bring children into this world. Hank and I believe in the power of prayer, and I think you have to have something you believe in to keep yourself from going crazy.

At the same time, though, there were still things we needed to do to keep our children safe. As a Black family, that meant talking with them at a young age about how to interact with police.

“Be polite. Follow orders,” we would say. “Less talk is best, but respond to the officer with ‘Yes, officer,’ ‘Yes, sir,’ or ‘Yes, ma’am.’”

This isn’t new to Black parents anywhere around the country, especially when their children are learning to drive.

“Keep your hands on the steering wheel. Have your ID on you at all times. If they ask you to get out of the car, get out of the car.

“Forget about justice,” we would say. “Just come home.”

When Henry was 16 years old, he got stopped around 11 p.m. just north of the county in which we live. When a black man drives a car with different plates than the city where he’s driving, it’s often assumed the vehicle is stolen.

That night, he was running late for curfew, and the area where he got pulled over has a 30 m.p.h. speed limit. He was going 40.

The stop started with one police car, but it ended with two.

Four police officers for one young black man.

Henry was asked to get out of the car.

They had no reason to ask him to get out of the car, but if he didn’t, he would’ve been disobeying an order from an officer.

By the time Henry made it home, he was 30 minutes late for curfew. Hank and I were starting to get really concerned. Henry never missed curfew.

“Mom…” I will never forget how shaken he looked as he told us what had happened. “My first instinct was to run. I was so scared. But I remembered everything Dad had taught me.”

I instantly began praying, “Thank you, Jesus, thank you for being there for my son. I thank you for being there with the police officers.”

The goal is for our children to always get home alive. Praise God, on that night, Henry did.

Hank has been stopped multiple times for “driving while Black.” When we lived in Colorado, we had a Jaguar. Actually, it was my car, but Hank was frequently stopped when he drove it by himself. It happens often to Black men who drive nice cars in a predominantly White neighborhood.

And then? “Well, sir, we were looking for someone who fits your description.” And the description is always the same: just “a Black man.”

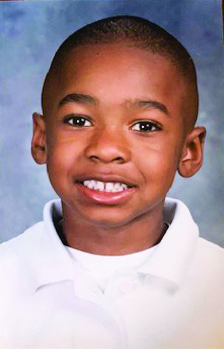

Unfortunately, profiling starts at a very young age. We talked with Henry when he was 8 years old about the police because, by then, he was old enough that we allowed him to go with his friends’ families to do things.

In middle school, he and his friends were doing more things by themselves, so we would always make it a point to remind him not to go into a gas station to get candy or a soda unless he was with his big sister or one of us. Even then, you don’t take a backpack in with you. You can’t go in with your friends when the bus stops because two or three little Black kids who are just joking around could automatically be profiled.

They get called out. Then they get scared. Then they start running. Then they get shot.

That’s a call no parent ever wants to get.

At Wabash, Henry continued dating his girlfriend who is White. I knew he would experience more situations where people could be suspicious of him and his intentions. Here was this Black, muscular football player who wore a hoodie and had a beard walking and driving around with a young White woman. Imagine.

At Wabash, Henry continued dating his girlfriend who is White. I knew he would experience more situations where people could be suspicious of him and his intentions. Here was this Black, muscular football player who wore a hoodie and had a beard walking and driving around with a young White woman. Imagine.

So many people in the White community are just now realizing what their Black friends have experienced for generations. It was only because someone had a cell phone out at the right time that we know what happened to George Floyd. But this has been happening for so long.

So, White friends, please do not say, “I understand.” How can you? Perhaps you can say, “I can’t even imagine how you must feel.” Ask your Black friends, “How is this affecting you? What can I do to support you during this time?”

And mean it.

Be open to listening and taking action. There are numerous ways to support your Black friends. It’s not limited to protests. Oftentimes, it can be uncomfortable confronting your friends and relatives. You may want to walk away.

But your silence equals complicity.

And please do not say, “I don’t see color.” We understand that you love us, but it comes across as wanting to ignore what’s going on. Differences are meant to be seen and to be celebrated.

Henry is a Black man. Dominique is a Black woman. See them.

I often say to my children that we are blessed beyond measure because God made promises to our ancestors. When my kids thought a situation they were facing was hard, I would remind them that our ancestors chose to live. They accepted the rape, the branding, all that came with slavery so we that we could make a difference.

That’s our purpose, and I hope that’s our legacy.

What will your legacy be?

Dr. Patsy WebberHunt is the mother of Henry WebberHunt ’18. She and her husband, Hank, are former members of the Parent Advisory Council. They reside in Indianapolis, Indiana.