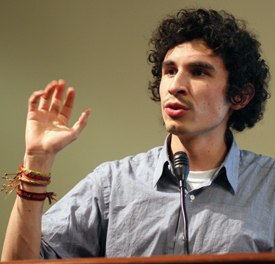

Wednesday night, a panel of men spearheaded by Alejandro Maya ’13 attempted to project a vision of a brighter future through their presentation entitled “A Night of Dreaming: Discussing the Dream Act.”

Maya began his speech with a haunting refrain, “I asked professors about the Dream Act, and they gave me blank stares. I asked students about the Dream Act, and they gave me blank stares. Our mission is to inform, and second, to gain support from you.

.jpg) Presentations and conversations have been taking place across the U.S. about the Dream Act since its introduction in 2001. Many have been silenced by fear, segregation, and discrimination. The only thing that separates them from us is a piece of paper.”

Presentations and conversations have been taking place across the U.S. about the Dream Act since its introduction in 2001. Many have been silenced by fear, segregation, and discrimination. The only thing that separates them from us is a piece of paper.”

The reason for Maya’s solemnity is the Dream Act, or the “Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act,” a weighty piece of legislation that would grant undocumented immigrant students up to six years of legal residence, during which they would have an opportunity to earn the right to apply for permanent residency.

In order to even be eligible for the temporary six-year residency, students would have to meet four qualities: having lived in the U.S. for at least five years before the bill passes, having been in the U.S. at the age of 15 or younger, having graduated from a U.S. high school or received a G.E.D., and having demonstrated good moral character (i.e. avoiding criminal behavior or liability as a security risk).

If these four qualities are met, the student is eligible for temporary residency and can earn permanent residency during those six years by meeting one of the following conditions: graduating from a two-year college, completing two years toward a four-year degree, or serving in the military for at least two years.

Maya then relinquished the podium to the men comprising the panel, Jose Herrera ‘13, Garrett Wilson ’13, Professor of History Richard Warner, Rudy Altergott ’13, and guest speaker Isaias Guerrero from the Latino Youth Collective. Each explored the Dream Act from a different angle.

Herrera spoke first and explained the bill itself, noting that it was voted down in 2001, 2006, and 2007,

“In 2008, Democrat Richard Dubin of Illinois and Republicans Charles Hagel of Nebraska and Richard Lugar of Indiana re-introduced the bill. It failed by a mere eight votes for legislative consideration.

I cannot stress enough that the bill is not amnesty. Certain criteria must be met, applications must be filled out, and this applies to all immigrants, not just Hispanics. It’s a chance for education.

The law currently prohibits thousands of citizens from going to college. These children had no choice; they have lived here for most of their life. We are losing aspiring doctors, lawyers, and artists.

Currently, only one out of every twenty immigrants who graduate from high school attends college and those that do are denied federal financial aid and sometimes in-state tuition rates. And, after graduating, they have to work for minimum wage and live in constant fear of deportation.

Currently, only one out of every twenty immigrants who graduate from high school attends college and those that do are denied federal financial aid and sometimes in-state tuition rates. And, after graduating, they have to work for minimum wage and live in constant fear of deportation.

The Dream Act levels the playing field. The undocumented students will still not be eligible for financial aid and will actually end up paying more than citizens.”

Wilson also addressed the issue of whether or not the Dream Act would harm the economic well-being of current citizens,

“Some claim that these immigrants are taking our resources. They have been.”

Wilson explained state and local taxpayers are already investing in the education of these children in elementary and secondary school.

“The immigrant child is just like any other American child, just like you or me. These students consider their home the U.S. Many of them have no recollection of their country of origin.”

Wilson argued that the Dream Act would be financially beneficial as well, “It makes economic and humanitarian sense. A single person with a Bachelor’s degree who earns an average $60,000 of taxable income will contribute $9,640 to taxes and welfare annually; in a 40-year span he/she will have contributed $385,000.

In April 2005, the Army Reserve failed to meet their quote of new recruits. 7,200 of the 180,000 new recruits each year are non-citizens.”

In April 2005, the Army Reserve failed to meet their quote of new recruits. 7,200 of the 180,000 new recruits each year are non-citizens.”

After Wilson concluded, a drastic change in the mood of the program took place as Professor Warner stood up to speak and began a slightly more informal anecdote,

“In a world that doesn’t really value complexity, it’s worth thinking about this issue with a bit of dispassionate rationality. If the U.S. wanted to, it could close down illegal immigration tomorrow. Part of the problem is that the U.S. and Mexico share the largest economic difference in the world of any two bordering nations. Let’s use the term ‘undocumented,’ because no human can be illegal.”

Warner went on to relate the story of a person friend whom he disguised with the name “Ricardo”, a man who “lived his entire conscious life in the U.S.” but arrived at the age of four. “Ricardo” graduated from high school and was luckily accepted into a private four-year college.

“He was a stellar student and was pre-med. But he couldn’t get into medical school; the state universities that offered the program wouldn’t accept him. He could have been a great bilingual, bi-cultural doctor, and there’s definitely a business there. Now? He bags groceries”

Warner contrasted that with the story of another man who grew up in New England, the son of a professor and a high school teacher, “privileged by virtue of birth, but lazy,” who took six years to finish undergraduate school and spent “ten years goofing around in the restaurant business” before going back to school to earn his Master’s degree and P.H.D.

Warner contrasted that with the story of another man who grew up in New England, the son of a professor and a high school teacher, “privileged by virtue of birth, but lazy,” who took six years to finish undergraduate school and spent “ten years goofing around in the restaurant business” before going back to school to earn his Master’s degree and P.H.D.

Then startlingly, Warner proclaimed “I am that man. There is a human aspect to this issue that you should think about it.”

After a stunned silence, Rudy Altergott claimed the podium, stressing the bipartisan nature of the bill and imploring the community to write to their congressmen, educate their peers on the act, and talk to President White about the act.

“This night is about fulfilling dreams, not our dreams, but others…the University of Michigan, the presidents of Harvard and Stanford, the UC Berkely Chancellor, institutions such as College Board and the National Education Association-which has 3.2 million members- have all declared their support for the bill.

This is unconventional warfare. We are trying to win the hearts and minds of our congressmen.”

The last speaker of the night, Isaias Guerrero, an immigrant from Colombia and representative of the Latino Youth Coalition, related his personal experience,

“I lived in Colombia in the 90’s when there were still problems with guerrillas and drug dealers. We’d wake up to car bombs…it was normal in a way, the reality you would constantly see.

My family tried to apply for political asylum, but the process was too long, and we took a tourist visa of six months to get out. We’ve been here for nine years now. I’ve graduated from college here, but now people say, ‘Want this job? What’s your social security number?’”

Guerrero went on to explain the work he does at the Latino Youth Collective, a program that started as a “dropout prevention program” and describes its goal as providing “resources and opportunities for youth to engage in personal and community development through critical pedagogy, grassroots organizing, and collective action.”

Guerrero also encouraged interested community members to visit www.trailofdreams.net to read about four undocumented students trekking from Florida to Washington, D.C., in order to gain publicity.

“The goal is to build bridges between dreams and reality,” Guerrero said as the program came to a close, “As Césár Chávez said, ‘History will judge societies and governments — and their institutions — not by how big they are or how well they serve the rich and the powerful, but by how effectively they respond to the needs of the poor and the helpless.’”