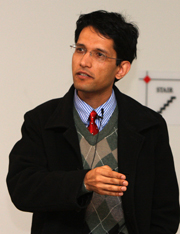

Gyanu Lamichhane ’99 sees the world as a very small place and sees it shrinking further with blinding speed. While globalization provides opportunities for the spread of knowledge and commerce, Gyanu is equally concerned about the spread of infectious diseases.

Presenting the Haines Lecture in Biochemistry, Lamichhane gave his perspective on education and human health in the globalized world. As an assistant professor in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, Lamichhane is literally up to his elbows in disease every day — specifically tuberculosis. In his research, he is studying the genes that power tuberculosis with hopes of creating vaccines that can fight the constantly mutating disease.

"The world has shrunk immeasurably in the last 10 years," Lamichhane said. "Infectious diseases can now migrate around the world very quickly."

"The world has shrunk immeasurably in the last 10 years," Lamichhane said. "Infectious diseases can now migrate around the world very quickly."

For context, he discussed "Typhoid Mary" Mallon’s immigration to the United States in 1883 and how she gradually spread typhoid bacillus throughout New York City over the course of decades.

He contrasted that with the endemic spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which infected thousands of people worldwide in a matter of months in 2002-2003 because of the rapid increase in worldwide airline traffic.

"Tuberculosis is the most successful pathogenic microbacteria in human history in terms of the number of deaths caused by it," he said. "Tuberculosis is severe and it is a respiratory syndrome, but it is chronic, not acute, so it doesn’t get the attention.

"The point is that things move very fast now. It’s not difficult to get to the other side of the world. The massiveness of global trade is very high… a lot of people are moving and taking with them bugs that travel quickly."

Lamichhane, who left Wabash to earn his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, said there were 9.2 million estimated new cases of tuberculosis in 2008 that led to approximately 1.7 million deaths. Multidrug resistant (MDR) strains accounted for 424,000 cases and 116,000 deaths. Extensively drug resistant (XDR) tuberculosis cases numbered 27,000 with 16,000 resulting deaths.

"That’s 16,000 people around the world getting an infectious disease that cannot be treated and is transmitted by a simple cough."

Lamichhane, who himself has latent tuberculosis, noted the skyrocketing number of TB deaths in Africa from 1990-2005. He said that the growing morbidity rate is due to the large population that has compromised immune systems from HIV. He cited a Harvard study of 53 people who were dually infected with HIV and MDR-TB and 52 died within three weeks. "HIV weakened their immunity, which allowed the latent tuberculosis to progress to a stage where it simply couldn’t be treated," he said.

Lamichhane, who himself has latent tuberculosis, noted the skyrocketing number of TB deaths in Africa from 1990-2005. He said that the growing morbidity rate is due to the large population that has compromised immune systems from HIV. He cited a Harvard study of 53 people who were dually infected with HIV and MDR-TB and 52 died within three weeks. "HIV weakened their immunity, which allowed the latent tuberculosis to progress to a stage where it simply couldn’t be treated," he said.

Two billion people worldwide are carrying tuberculosis bacteria; one in 10 will develop tuberculosis in their lifetimes.

"We don’t need to worry about the two billion people infected with tuberculosis," he said. "We should be concerned about those with MDR and XDR TB.

"Tuberculosis is a disease that’s been gone from our memory for a long time, but with globalization, we need to be concerned about it all over again."

At Johns Hopkins, Lamichhane is a part of the Tuberculosis Animal Research and Gene Evaluation Taskforce (TARGET), which identifies the genes necessary for tuberculosis to survive in the lungs of mice and other animals. He was the the Paul Ehrlich Award Winner as an outstanding young scientist at Johns Hopkins, and his research was featured in Esquire magazine's 2007 "Best and Brightest" issue.

"Currently we are trying to find genes whose functions are required for survival and growth in vivo in the mouse model of tuberculosis," Lamichhane says on his website. "These genes would be rational targets for new anti-tuberculosis drugs."

His Haines Lecture was equal parts infectious disease spread and the globalization of our world. "The world has globalized. In Nepal where I come from, the kids in high school all have iPods, mobile phones, and wear Kobe Bryant jerseys just as they do here."

His point was that people now travel relatively freely across borders, borders in the commercial world are largely permeable, and as a result, pathogens can also travel freely across borders.

"Tuberculosis is a global disease," he said. He reminded his audience of students, staff, and faculty — including many of his former professors — that the first drug to combat TB was streptomycin and that it was developed in 1944 by a global team of scientists.

He said students of liberal arts colleges like Wabash are already receiving a globalized type of education and will be uniquely positioned to solve the world’s future major problems, which will be global in nature.

"The dialysis membrane of the world has been removed… and tuberculosis doesn’t know or care where it is."