Joy Castro is assistant professor of

English at Wabash. Her work on the

American modernist Margery Latimer

is published in American National

Biography and the Review of Contemporary Fiction, and her short

fiction and essays have appeared in North American Review, Mid-American

Review, Puerto del Sol, Quarterly West, and Indianapolis

Monthly.

Professor Castro will offer her first writing workshop at the Family Crisis

Shelter this September.

Magazine

Summer/Fall 2002

Shelter

“Maybe it’s an exaggeration to claim that

reading and writing saved me. I don’t think so.”

by Joy Castro

Before there were counselors and therapists, there were books. There were

books stuffed in the torn lining of my winter coat and smuggled home to

read on the school bus, to read after dark in a trailer where books were

not allowed.

Books, and the hope they carried, existed in rural West Virginia before

domestic violence shelters did, and they kept me alive when my mother

turned the rusted car around, halfway through Ohio, sobbing, knowing she

had nowhere else to go but back. Back to my stepfather, to a house where

blood, bruises, and rape were regular events, where contempt and fear

were the sea we swam in, where only police and prison would finally free

us.

There were books like Maya Angelou’s classic memoir of abuse and poverty I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in its crackly plastic cover, suggested by Mrs. McCarthy, the middle-school librarian who lived farther down the dirt road than we did, who drove past every day in her red Cherokee Chief. (What did she see, or guess?) And there was rich escapism, too: Tolkien’s trilogy, with its blessedly simple demarcations of good and evil, and a whole shelf’s worth of Helen MacInnes’s Cold War espionage novels, in which Oxford dons and their pretty wives stumble into intrigue abroad, wittily eluding disaster. There was one crucial old 1950s hardback, the title of which I can’t recall and which I never got to finish; my mother found it. It featured a girl who went to college, something our religion forbade and which no one in our family had done. The book disappeared, but I began to plot a private future.

When we moved hours away to an unimproved piece of land and knew no one,

there was the old pink paperback my English teacher Mr. Elkins gave me

at the end of freshman year. The Brothers Karamazov? Never heard

of it.

“Try it,” he said. “Trust me.”

It was my first exposure to the shell-shocked sensibilities of Dostoevsky,

whose characters struggled to understand how a good God could allow cruelty

to innocents. That summer, I was sent out every day to dig the ditch where

the gas line to our trailer would go. I hid the book in different places

in my room and then smuggled it out to the ditch in the back waistband

of my jeans (I was skinnier then: missing meals was a punishment). And

when I got so exhausted I couldn't dig another shovelful, I'd stand there

and read Dostoevsky, ready to shove it back in my jeans if my stepfather

came around the bend to check on me. Then I'd dig, and the story would

keep going in my head. Then I'd read and correct where I went wrong. I

read the whole book that way.

I still have the diary I kept during those years, and I cannot quote from

it to you. They’re too desperate and sad, those things I wrote, the

handwriting jagging and scraping up and down in the lines like the ink

trail of a seismograph’s needle. I can’t quote from it, but

that little blue-bound diary with its cheap gilt edging made the difference

to me between terrorized silence and a voice, a vision, a version of events—however

tiny—that was still my own. It kept me from repressing, it kept me

from forgetting, when I ran away at fourteen.

Maybe it’s an exaggeration to claim that reading and writing saved

me. I don’t think so.

"It's now common knowledge--bibliotherapy is the term--that reading

books can offer new models for living, new concepts and interpretations

for howwe see our lives. Telling one’s story, too—out loud or

on the page—can function as a form of healing. Psychology professor

Brenda Bankart, who does research in the field, explains that narrative

psychology takes the point of view that human beings create who they are

through the stories they tell about themselves. That is, we come to understand

the meaning of our lives as we explain our actions and feelings to others.

Journal writing is yet another way to begin a healing process by bringing

one's interpretation of events to awareness. Sometimes just writing the

story, simply, for oneself or for an imaginary audience helps us weave

together the specific, seemingly unrelated events that together make our

lives a meaningful whole. The gift of a journal, then, can provide someone

with the opportunity to begin healing.

This spring, Professor Bankart, Associate Dean Edie Simms (who has done

counseling work in domestic violence shelters), and I invited Wabash,

via an all-campus e-mail, to contribute journals and books to the Family

Crisis Shelter here in Montgomery County.

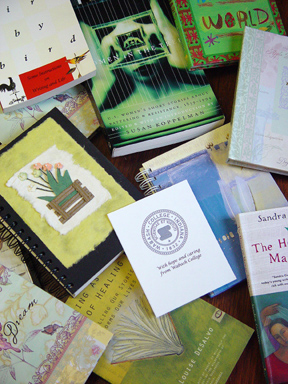

The response was amazing. By mid-May, students, staff, faculty, and retirees

had contributed over sixty journals to the project, along with multiple

copies of several books such as the do-it-yourself guide Writing as

a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives by

Louise DeSalvo; the groundbreaking collection Women in the Trees: U.S.

Women's Short Stories About Battering and Resistance, 1839-1994, edited

by Susan Koppelman; and Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street,

a work of fiction about a young Latina who creates a positive future

for herself (through writing, incidentally) despite the poverty, prejudice

and abuse that surround her. In the front of each journal and book, we

affixed a bookplate that reads, "With hope and caring from Wabash

College." New journals will be offered to residents upon their arrival,

and the books will remain available to all residents as part of the Shelter’s

permanent collection.

I was moved by the outpouring of generosity from people all across campus,

from the retired faculty member, to the student working to pay for college,

to the professor whose gift included this stark note:

"This donation is made in memory of Phyllis Majors, a little girl

I grew up with. She was shot by her ex-husband after she took out a restraining

order against him."

I heard several such stories as donations came in. Directly or indirectly,

domestic violence has hurt so many.

Last year alone, our local Shelter served 239 abuse survivors; an estimated

three million children are abused in the U.S. each year. Severe domestic

trauma and suffering continue to exist all around us, often invisibly,

and some kinds of abuse can cause neurobiological damage as severe and

long-lasting as the post-traumatic stress disorder suffered by combat

veterans. Clearly, there continues to be a need for hope and healing.

Unlike therapists, journals pack easily and cost little: for people in

upheaval, they can be a crucial part of healing. The campus’s generous

response to this spring’s journals project, as well as to the recent

benefit concert for the Shelter and last fall’s Monon Bell fund drive,

suggests Wabash’s widespread recognition and appreciation of the

Family Crisis Shelter’s valuable work. It makes me proud.

Good books offer us the liberating potential of imagining other lives,

lives different from—and sometimes better than—our own. They

offer us catharsis, affirmation, and new models for living. Writing offers

us the chance to record, to bear witness, to grieve, to express outrage,

and finally to sketch on the page new possibilities for ourselves, new

dreams.

What

are your thoughts?

Click

here to submit feedback on this story.

Return to the table of contents