"These guys—yes, they're mostly guys—are

ruthless. They rip each other to shreds with no hesitation. If you can't

leave your ego at the door, you're going to be a very unhappy hacker."

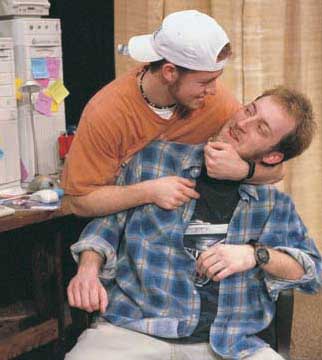

Zach Hoover ’01 and Ryan Soard ’01 wrestle at the keyboard during a scene from Deadfish, Idaho.

Read a scene

from Deadfish, Idaho

"There are people who get a kick out of breaking into other people's systems. They proclaim themselves hackers, but real hackers call these morons crackers and want nothing to do with them.

The media continues to confuse these, but the difference is simple: hackers build things, crackers break things."

Contact Professor Abbott by e-mail: abbottm@wabash.edu

Magazine

Summer/Fall 2001

HackerPhreaks and CyberGeeks

by Mike Abbott ’85

Associate Professor of Theater

In January of 1979, I waged scholastic warfare with my best friend, Mike

Frye. We were 15 years old. Our rivalry, which began years before in elementary

school, had gradually grown more intense. Where once we had competed on

spelling tests, SRA reading levels, and who could read Charlie and

the Chocolate Factory the most times; suddenly it all became serious.

I had just won the DAR Prize. It was a staggering moment of victory. The

American Legion Award was less than a month away, and I felt certain that

if I could win it, Frye would be a broken man.

Then Frye called me up. He had something important to show me. When I

arrived, it was there on his desk: a brand new Tandy TRS-80 Model IV computer—the

very system we spent countless hours playing with at the local Radio Shack,

until the store manager kicked us out. I looked at the black and silver

gray box on Frye's desk and realized right there and then that I had lost.

I could only look on with envy.

We spent the next six months learning everything we could about the computer.

It had an 8-inch monochrome screen and whopping 4K of onboard RAM. No

printer, no modem, and only a cassette tape for program storage. It ran

Level II Basic and came with the Casino Games Pack and Invasion Force.

It didn't take us long to discover, however, that our interests in computing

were very different. I just loved playing with the damned thing. I have

never gotten over my sense of amazement with computers. I love to uncover

and try all the possible options and configurations on a system. To me,

it's all about the interface-how we interact with these machines, and

how we teach each other our languages.

Frye wasn't interested in playing with the machine. Frye wanted to be

a coder. Frye's favorite book was the Mostek Z80 instruction set reference

guide, which was the Geek bible of its day. All of his early attempts

at programming were assembled with paper and pencil, using the Mostek

book as a reference, and then typing in each piece of code manually. The

best parallel I can think of is the Native American process of additive

color dying used in the making of thread used for weaving fabrics. Before

you can weave the strands together to make the fabric, you must know the

"codes" for which dye combinations are required to achieve the

colors you want to use.

I have no interest in this kind of painstaking work, but watching Frye

gave me some insight into, and longstanding respect for, the nature of

programmers.

By the time I came to Wabash in 1981, I had saved enough money to buy

my own computer: an Atari 800 XL with a whopping 16K of RAM. After moving

to New York four years later, I acquired an Atari 520ST and wrote my graduate

thesis on it. It was the first computer I actually relied on. I had to

trust this thing.

I also had to trust myself: I wanted to upgrade the memory to one megabyte;

Atari had no service centers, so I was on my own. This meant I would have

to open the case and install the replacement chips myself. This was a

geeks-only operation. The subset of theater people who also solder their

own memory chip upgrades is very small. I needed help.

I found it at the New York City Atari User's Group-a collection of Atari

computer enthusiasts who met on the first Tuesday of every month to share

ideas, swap software, and drink Schaffer's, possibly the worst beer made

in North America.

These guys-and they were all guys-showed me how to install the upgrade,

but that was the least of what I learned. That night I had my first look

at geeks in their natural habitat. That meeting-and I attended nearly

every one for four years-gave me my first glimpse of hacker culture.

Hackers essentially do two things: solve problems and build things. They

believe in voluntary cooperation and information sharing. They have an

instinctive hostility to censorship and secrecy. The cardinal sin in hackerdom

is selfishness. You contribute by improving on what others have done and

allowing others to improve what you have done.

In The Cathedral and the Bazaar, Eric S. Raymond lists five tenets

of hackerdom:

1. The world is full of fascinating problems waiting to be solved.

2. Nobody should ever have to solve a problem twice.

3. Boredom and drudgery are evil.

4. Freedom is good.

5. Attitude is no substitute for competence.

There are people (mostly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking

into other people's systems. They proclaim themselves hackers, but real

hackers call these morons crackers and want nothing to do with them. The

media continues to confuse these, but the difference is simple: hackers

build things, crackers break things.

After Atari pulled out of the hardware business, my interest in computers

shifted. In 1993 a friend of mine showed me a new operating system that

he claimed would eventually "blow Microsoft out of the water."

It was called Linux. Today, it's my primary operating system, and has

become the second most popular operating system worldwide, recently surpassing

MacIntosh in total number of users.

Linux is subversive. It's the most notable and successful outcome of the

open source software movement. Nobody owns Linux. There's no Linux, Inc.

In 1991, the inventor of Linux, Linus Torvald, released the source code

for Linux into the public domain. In the years since, thousands of programmers

from all over the world have worked together to improve it. Today it is

probably the most stable OS on the planet. It almost never crashes. For

this reason, and a few others, it's become the main engine that keeps

the Internet running.

Linux is the OS of choice for most hackers. Given the anti-authoritarian

nature of most coders, it's easy to understand why most of them choose

to run Linux.

I'm not a hacker. I have only a rudimentary knowledge of programming. My real interest is in the culture surrounding hackers. To write my play, Deadfish, Idaho, I needed to get a closer look at coders doing their thing in the pressurized environment of a release deadline. There's really only one place to do this: the epicenter of hacker culture-Silicon Valley. So last July I traveled there.

One of the things I found most impressive about Silicon Valley is the

collaborative relationship that most coders forge with each other. You'd

think I could easily relate to this environment, given that the nature

of my work in theater is so collaborative, but what I saw there was like

nothing I've ever seen. These guys—yes, they're mostly guys-are ruthless.

They rip each other to shreds with no hesitation. If you can't leave your

ego at the door, you're going to be a very unhappy hacker. There's just

no time for diplomacy or ego massage. It's all about optimizing performance

and lowering the crash threshold. Nobody takes criticism personally. It's

the work. It's always the work.

When we began our preliminary production meetings for Deadfish, costume

designer Laura Conners, set designer James Gross, and I decided we would

attempt to emulate this open collaborative environment. Frankly, I don't

think we succeeded. We were able to open our channels of communication

a bit wider, but I simply don't think we're conditioned to deal with each

other quite that honestly. I'm personally uncomfortable with the brutality

of it all.

If I was thrust into the middle of it, I suppose I would gradually adopt

the coder mode of communication; but artists don't generally work this

way. Our egos are too imbedded in the work.

But I do believe there's a strong connection between what artists do and

what coders do. I'm willing to go so far as to say that I believe the

best coders are artists. They translate ideas and inspiration into original

creations that tend to reflect their own personalities. They have a natural

affinity for beauty and design. There is, in fact, such a thing as beautiful

code.

Even though I'm not a coder, I have an abiding respect and fascination

for what they do, and it's not difficult to imagine what that beautiful

code might look like.

Return to the table of contents