Michael Mandelbaum, a leading authority on international affairs believes Russia, China and the Arab world are areas where democracy could grow. But the Director of the American Foreign Policy Program at Johns Hopkins University thinks the Arab world and Iraq present the biggest challenges.

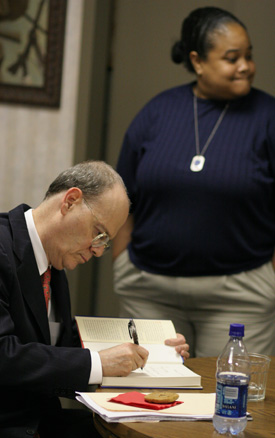

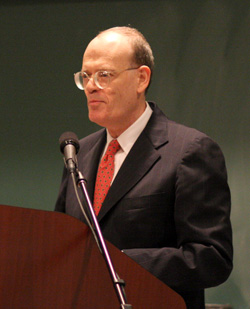

Mandelbaum delivered the 2007 Benjamin A. Rogge Memorial Lecture Friday night. The noted political scientist and author titled his speech same as his current book, Democracy’s Good Name: The Rise and Risks of the World’s Most Popular Form of Government.

Mandelbaum delivered the 2007 Benjamin A. Rogge Memorial Lecture Friday night. The noted political scientist and author titled his speech same as his current book, Democracy’s Good Name: The Rise and Risks of the World’s Most Popular Form of Government.

"The prospects are distinctly poor for a number of reasons in the Arab world," Mandelbaum said. He cited historical, cultural, and religious reasons as why Arab countries are poor choices for democracy. "And there is a distrust and history of anti-western sentiment."

He said in picking Iraq the U.S. eliminated obstacles to democracy ousting dictator Saddam Hussein, but otherwise didn’t choose an easy target. He added that when countries have such strong ethnic, natural and religious reasons plus the distrust of the west, it’s unusual to have any form of government. Instead, he suggested, they have civil war. He cited not just Iraq but similar scenarios in Bosnia and Kosovo.

Democracy can be imported but not exported, Mandelbaum suggested. "I think the United States government now would settle for stability (in Iraq), for them to quit shooting their neighbors, and not be a host for terrorism."

The only other option is to occupy Iraq similar to what the British did in India while building institutions. "And that’s just not politically feasible," he said.

Conversely, he holds hope that Russia and China could one day be democracies. He doesn’t believe Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hard-line policies will have a long term impact. With an improving free market economy and growing middle class, democracy is likely to grow.

China is a more interesting case provoking the adage of irresistible force versus the immovable object, Mandelbaum said. The irresistible force is the country’s economic growth versus its communist form of government.

Mandelbaum spent the first half of his lecture talking about democracy and its two primary components, as he’s found in his research. He described sovereignty or free elections and liberty or freedom as the two most important attributes.

Mandelbaum spent the first half of his lecture talking about democracy and its two primary components, as he’s found in his research. He described sovereignty or free elections and liberty or freedom as the two most important attributes.

While free elections might be made possible through changing the form of government, liberty doesn’t come as easily. "Liberty has to be homegrown," he said. "It has to be adopted. Democracy is not like a pizza – it can't be ordered elsewhere and delivered."

He said his look at history indicates it takes at least a full generation to establish liberty.

Free elections are no guarantee of democracy. Mandelbaum used Hamas’ victory in Palestinian parliamentary elections as an example. But Hamas "certainly doesn’t favor liberty when it comes to religion."

Despite the struggles of exporting democracy, Mandelbaum noted its growth. In 1900 there were 10 democracies in the world, 30 such forms of government in 1950 and in 2005 there were 119 democracies.

The new democracies of the last century elected to build such forms of government, he suggested, because democracies won the world wars and had the strongest economies.

"The United States has promoted democracies by being an example – which is exactly what the founding fathers had in mind."