|

March 24, 2002

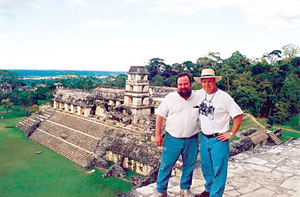

When I asked senior Joe Orozco at our farewell dinner to explain the unusual camaraderie of this group of students, he answered easily. "A lot of it is because of Warner and Rogers." The history professor who once cooked for Pete Seeger and the Spanish professor who fell in love with Spanish literature as a Mormon missionary reading the forbidden One Hundred Years of Solitude have two very strong and potentially antagonist personalities. Witness Rogers’ calm demeanor as he waited at the airport for Wabash staff to bring the passport he’d left in Crawfordsville. He passed the time getting a notarized affidavit of citizenship. Warner shuttled nervously between the airline counter and the security check, moving among the students like a sheepdog and eyeing his watch every 30 seconds. | |  | | Professors Warner and Rogers outside the tomb of Pacal the Great at Palenque. | "I’ve never found a problem that I couldn’t get around," Rogers said as Warner walked quickly back to the gate. "You know, I think Rick is a bit of a worry wart." Warner has a motto of his own—"prior planning prevents piss-poor performance." But Rogers and Warner—nicknamed Padre y Hijo (father and son) after an indigenous woman confused Warner for Rogers’ father, much to Dan’s delight—share a love of Mexico, a respect for each other’s intellect, and a passion for pushing Wabash students to take risks and learn. It was a perfect match. While Rogers’ knowledge of Aztec history made him the ideal guide through Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology, Warner’s skeptical eye as an ethnohistorian nudged students to think critically about archaeological issues in the ruins we explored. Where Rogers was always pushing the group ahead, Warner kept an eye out for the stragglers. And their genuine enjoyment of Wabash students was never more apparent than on bus trips, when they’d often shun the front seats reserved for them to hang out with students in the back. Rogers’ ability to strike up conversations with complete strangers paid off more than once for the students. While speaking with an indigenous man at Agua Azul, he casually referenced having seen Zapatista leader Subcommander Marcos in Mexico City during his triumphant entry the previous year. "I was there too, although you wouldn’t have recognized me," the man said. A Zapatista himself, he’d worn the black hood the rebels don to avoid being identified. The resulting discussion Rogers had with the man about an indigenous rights conference being held nearby brought us an insider’s reaction to current political events in the region. If David and Nancy Orr showed students how to live in a new culture and reach out to it, Warner and Rogers showed them how to embrace and revel in it. As Joe Orozco said:

"Their excitement for this place, the way they get along, work things out; they set the tone for the whole trip."

|