The Art of the Question

"The art of Samuel Bak entrances. It also disquiets."

So write Wabash College Dean of the College Gary Phillips and Drew

University Theological School Professor Danna Fewell in their

introduction to the catalog for "The Art of the Question: The Paintings

of Samuel Bak," which opens Monday, March 2 in the Eric Dean Gallery at

the College's Fine Arts Center.

In this album you'll find a sampling from the many works in the

exhibition, along with some of the teaching material Professors Phillips

and Fewell, have prepared for the show.

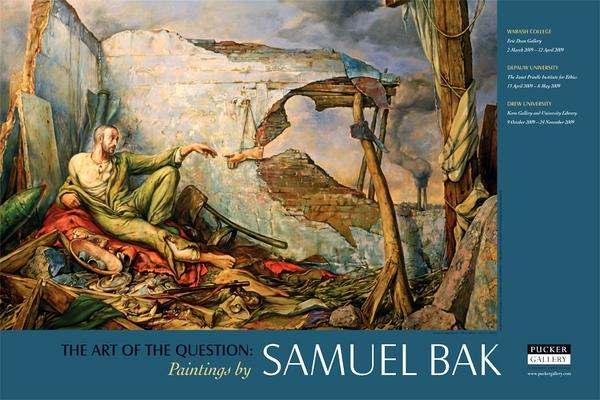

"Creation of Wartime III"

The various figures of Adam in soiled uniform, prison coveralls, or

refugee garb are contemporary representatives of the one who was

banished from Paradise. Like him they must feel that they were dumped

into this world, unasked. How can they rise from the rubble where they

have landed? Perhaps this explains why they are all in search of God.

The most they come up with in my paintings is some mysterious shape,

perhaps a hand that signals meaning they must discover themselves.

My imagery derives, of course, from Michelangelo’s Creation of Man, at

whose center Gods and Adam’s pointing fingers almost touch. What do

these fingers mean to me? The hands seem to be of similar size. Is God

creating man in his image, or is this man’s creation of God? Could their

gestures express any disappointment or accusation?

—Samuel Bak

"Figure with Flight Assistant"

The angel takes a different form in "Figure with Flight Assistant,"

being simultaneously angel, airplane, and Icarus, whose inventor father

Daedalus may or may not be the character with the breathing apparatus

whose hose is in Icarus’s hand. Whatever their identity beneath their

respective half-masks (between one’s goggles and the other’s mask they

expose a single complete face) their destinies are intertwined: they

have begun together to seek the means of human flight and eventual

freedom.

—Paul T. Nagano, Samuel Bak: The Past Continues

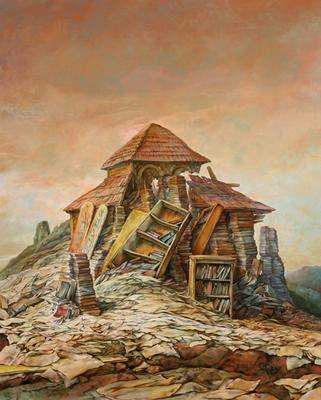

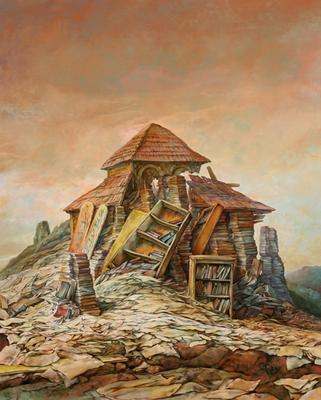

"The Nature of Roots"

The spiritually complex and perilous journey from ruin to restoration is

embodied in the difficulty of the transit, a process vividly dramatized

by a painting like "The Nature of Roots," where Bak’s fondness for

fusing disparate materials results in a ladder with tree roots for a

base.

Here many roles have been transformed. Once it was the nature of roots

to plunge deeper into the earth in quest of life-giving moisture. The

Jewish equivalent of that pursuit has been brutally severed by Nazi

expulsions – a favorite German euphemism for extermination was

ausrotten, to uproot.

But since the putting down of physical roots in a Jewish homeland always

implied a spiritual yearning for a heavenly connection, Bak’s torn up

roots become a ladder raised toward the sky.

The damage done below, however, has its parallel in the rent above, a

far more portentous injury, since roots are portable, if salvaged in

time, in a way that spirit is not.

An anonymous angel gestures with the ever-present hand, but who can read

accurately its enigmatic signal – if signal it is, and not a hopeless

wave of frustration?

—Lawrence Langer, In a Different Light: The Book of Genesis in

the Art of Samuel Bak

"For the Many Davids"

The young biblical David takes up unconventional arms to defend the name

of God. Indeed he claims his victory will be proof “that there is a God

in Israel.”

But while the David of biblical tradition triumphs, other Davids do not.

And we are led to wonder, yet again, how the survival or demise of

children and the presence of God are possibly related, and why we tell

stories in which children must defend God rather than the other way

around.

—Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A Phillips, Icon of Loss: The

Haunting Child of Samuel Bak

"Holding a Promise"

A downcast young Noah stands ready to launch a tiny skiff. A tattered

rainbow provides its rigging.

Has the promise of heavenly protection been restored? Or has the boy

cobbled together his own means of escape, crafting a refugee boat that

will set sail under his direction and power? He carries no cargo besides

himself and a bundle of sticks. Is this kindling intended for a

thanksgiving sacrifice to God once the flood has been safely navigated?

Or has this little Noah become Isaac, carrying wood for another burnt

offering orchestrated under false pretenses? Exactly what promise does

he portend? And what is its price?

—Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A Phillips, Icon of Loss: The

Haunting Child of Samuel Bak

"Solo"

Do Bak’s musicians frozen in a world of disrepair—suggesting a

performance but not actually playing—raise the question of whether or

not art has been trumped by the atrocities of the Shoah, or whether

hearing the music we once knew, or any music at all, is simply too much

of an indulgence given what we have we have seen?

Has the time for music-making ended?

—Charles Rix, “The End of Time: Bak’s Art, Messiaen’s Music, and

Levinas’s Ethics”

"Walled In", 2008

Here we see shades of the film Hitler loved so well: Fritz Lang’s

futuristic silent film Metropolis where workers’ bodies are ground into

dust and made into cement to build and operate the city that enslaves

them. Future fantasy becomes past fact as we witness children becoming

the fungible raw materials needed for fuel and defense in the Nazi

extermination campaign.

—Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A Phillips, Icon of Loss: The

Haunting Child of Samuel Bak

"Persistence"

Old, blue pages,

Purple traces on silver hair,

Words on parchment, created

Through thousands of years in despair.

As if protecting a baby

I run, bearing Jewish words,

I grope in every courtyard:

The spirit won’t be murdered by the hordes.

I reach my arm into the bonfire and am happy:

I got it, bravo! Mine are Amsterdam,

Worms, Livorno, Madrid, and YIVO.

How tormented am I by a page

Carried off by the smoke and winds!

Hidden poems come and choke me:

– Hide us in your labyrinth! —from Abraham Sutzkever, “Grains of Wheat”

Purple traces on silver hair,

Words on parchment, created

Through thousands of years in despair.

As if protecting a baby

I run, bearing Jewish words,

I grope in every courtyard:

The spirit won’t be murdered by the hordes.

I reach my arm into the bonfire and am happy:

I got it, bravo! Mine are Amsterdam,

Worms, Livorno, Madrid, and YIVO.

How tormented am I by a page

Carried off by the smoke and winds!

Hidden poems come and choke me:

– Hide us in your labyrinth! —from Abraham Sutzkever, “Grains of Wheat”

"Memorial"

The fractured, pieced together tablets of the Ten Commandments stand

simultaneously as a metaphor of the Sinai covenant that has been broken

by both humanity and God and as a headstone memorializing the six

million Jewish martyrs of the Shoah. The monument stands as though to

mark “Here lie the dead.”

But the bodies are not to be found nor is the god who once brought the

people out of the land of Egypt. The tablets stand in, mark a place, for

an absent deity and a missing people. Rusting double yods, letters

signifying the divine name, have been manually riveted to the top of one

of the tablets, a seemingly desperate and wishful imposition of divine

presence.

The people themselves are present only in traces: A dismembered and

roughly re-membered Star of David becomes the central picture of the

tablets’ puzzle, its form a sad example of the stone cutter’s and iron

worker’s arts. Here the identity of a people is pieced back together

after historical rupture, the rupture now integral to the identity of

those who are lost and those who remain, an insistent but uneasy

cohesion in an unstable and damaged structure.

The people are also engraved in the number 6, which alludes doubly to

the six million who perished in the Shoah and to the sixth commandment

“Thou shall not kill.” The number 6 both grieves and accuses. Implicated

in this cipher, as well as in the barbed wire, the prison-striped

salvage, the metal stays, and the bullet holes, are both the victims and

the perpetrators. Unspeakable suffering and the violence that has caused

it are inextricably bound together.

—Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A. Phillips, “From Bak to the Bible:

Imagination, Interpretation, and Tikkun Olam”

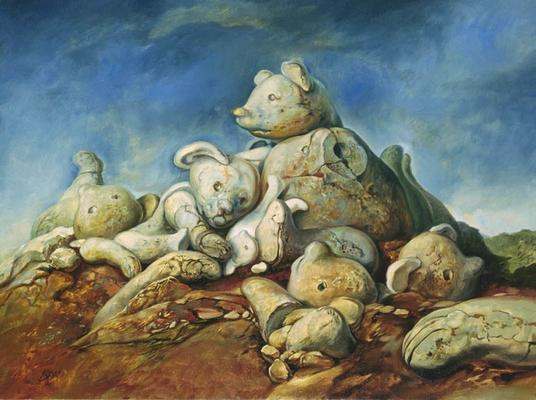

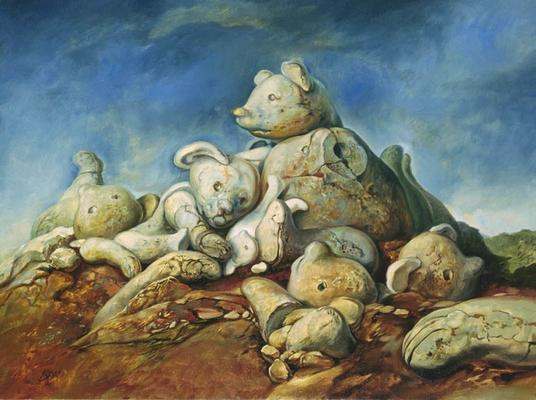

"Under a Blue Sky"

High in the wind and sun was my dwelling-place,

motherland, now you chain in the valley of

shadow your broken son; no comfort

now are the heavenly games of evening. Over the cliffs the skyscape is shining; I

dwelling in the depths, and stones are my company,

speechless; should I then be as they are?

Why do you write? Is it death? Who asks you?— Asks of your life a reckoning, asks of this

fragment of poem how it remains but a

fragment? Know this: unmourned, unburied,

I shall lie graveless, no vale shall rock me. Winds shall disperse my leavings; but listen, the

cliff shall re-echo – today, or tomorrow – the

song I am singing; boys and girls are

growing up now who will hear its meaning.

—Miklós Radnóti, “In a Troubled Hour”

January 10, 1939

motherland, now you chain in the valley of

shadow your broken son; no comfort

now are the heavenly games of evening. Over the cliffs the skyscape is shining; I

dwelling in the depths, and stones are my company,

speechless; should I then be as they are?

Why do you write? Is it death? Who asks you?— Asks of your life a reckoning, asks of this

fragment of poem how it remains but a

fragment? Know this: unmourned, unburied,

I shall lie graveless, no vale shall rock me. Winds shall disperse my leavings; but listen, the

cliff shall re-echo – today, or tomorrow – the

song I am singing; boys and girls are

growing up now who will hear its meaning.

—Miklós Radnóti, “In a Troubled Hour”

January 10, 1939