End Notes: Forever Keep Trueby Daniel Crofts ’63 |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

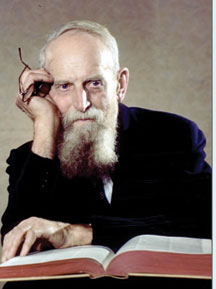

Several days later a rickety bus carried us to Qianxi (chee-EN-she), a more remote town. We found many more Christians and sat through the longest religious service of our lives, packed into a small room. Several elderly members of the Qianxi church remembered the tall, slender missionary who had lived there when they were young. He was the Westerner who had introduced tomatoes. That was proof positive—I had read about it already in his letters. He was my grandfather, Daniel Webster Crofts. Daniel had arrived in China in 1895 and spent 40 years—from 1904 to 1944—in the remote southwestern province of Guizhou (gway-joe, “noble region”), principally in the two towns we visited in 1993. Much of Guizhou province’s terrain consists of eroded limestone hills, a delight for traditional Chinese painters but too steep for agriculture, which is confined to narrow valleys and creeps up the hillsides on terraces. When Daniel lived there the province could barely feed its people in good crop years. In bad years, hunger and starvation stalked the land. Although I was named for my grandfather, I never really made his acquaintance. He lived his last years in Florida while I grew up in Chicago. We saw each other occasionally but were not close. The gulf between a provincial American adolescent and the seemingly gruff old man who often appeared absorbed by his own thoughts was too wide for either of us to bridge. Daniel’s death in June 1960, just after my freshman year at Wabash, made little impact on me. At that time, China was tightly closed. The Bamboo Curtain had slammed shut during the Korean War in the early 1950s. The outside world knew hardly anything about the ferocious Maoist revolution, or about the hardships it inflicted on the Chinese people. Though waged in their name (“The People’s Republic”), the revolution had run off the tracks entirely, we now realize, and had caused the most catastrophic man-made famine in world history. It would be decades before new leadership started to end China’s isolation and transform its shattered economy. For me China was out of sight and out of mind. My interests had been piqued by a striking spectacle closer to home, in the American South. The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s raised puzzling questions: Why were black Americans still on the outside looking in? Why had the promise of equality—supposedly encompassed in three landmark Constitutional amendments adopted between 1865 and 1870—been nullified for most of a century? My first faltering efforts to answer these questions took place at Wabash under the direction of Professor Steve Kurtz. He made the study of history come alive for me, and I shall be forever grateful. Eventually I became a specialist on the North-South sectional crisis that led to the Civil War. But in the late 1980s as a new China started to emerge and as my own scholarly career took shape, the basement of my childhood home in Chicago—carefully emptied by my brother Tom—yielded the historian’s ultimate treasure. We had thought that our grandfather’s China letters had been lost. Instead, many hundreds survived. A majority were written to our father, John, who had left China for the United States at the age of 17 and never returned. Even more surprising was the variety of the collection. It included Daniel’s poignant recollections of Verna Hammarén Crofts, his first wife and our grandmother. She had died young in 1909 just after escorting our father and his brother and sister down from their home in Zhenyuan to a boarding school in faraway Shandong. Several yellowed clippings from the North-China Herald revealed that Daniel wrote occasional columns for that English-language newspaper published in Shanghai, and further research on microfilm revealed many additional items. Until our visit to Guizhou in 1993, I hadn’t known what to do with these materials. Only then did I realize that they demanded a book. I was the one in the family who wrote about history, so this was a book that I would have to write. Doing it would honor the memory of my father, who spent his difficult formative years in China. It also would enable me to thank my daughter, Anita, who had studied intensive Chinese at Haverford College and then reestablished our family’s connection to China. Most of all, writing the book would allow me to know better my austere and forbidding grandfather, and tell the tale of a life lived on the cultural frontier. Between 2001 and 2005 I completed a first draft of the biography. Then Doug Merwin, who has gotten many books on Chinese topics into print, supplied the finishing touches. Upstream Odyssey: An American in China, 1895-1944 hasn’t become a best seller, but it has earned respectful assessments from scholars who know far more about China than I do. Students in my family history course at The College of New Jersey also have found it useful to read as I challenge them to write about someone in their own family tree. Daniel’s life offers important perspective on the Protestant missionary movement at the pinnacle of its influence. The Ohio farm boy who had worked his way through Muskingum College turned his back on the conventional life of a clergyman. Instead, he and Verna and thousands of other idealistic young Europeans and North Americans departed for distant lands at the end of the 19th century to bring about “the evangelization of the world in this generation.” It was the Age of Empire, but they made unlikely imperialists. No place so attracted Western missionaries as China, the earth’s most deeply rooted civilization. Daniel and Verna were members of the China Inland Mission (CIM), the brainchild of J. Hudson Taylor, its charismatic founder and leader. CIM missionaries shared a special élan. They attempted to carry the Christian Gospel beyond the treaty ports into China’s vast interior. And so it was that Daniel and Verna first encountered each other in Laohekou, far up the Han River, more than 1,000 miles from the coast. Both by conscious design and through long unconscious acclimation, Daniel adopted the ways of China. Following CIM custom, he dressed in Chinese fashion, with a long flowing gown, sandals, and —until the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911—a shaved forehead and a braided queue. Of course, Chinese attire could not enable him to appear more than superficially Chinese. His projecting Western nose, his hairy nostrils and hands, his severe-seeming rectitude, and above all his piercing blue eyes made him unmistakably exotic to Chinese observers. Many missionaries struggled to acquire adequate Chinese, but Daniel learned to speak flawlessly and to gain full command of the written language. He was known in China as Yong Bao Zhen (literally “Forever Keep True”). He recognized in China a sophisticated culture that had many attractive aspects. He realized, as many other missionaries did not, that China had stood strong before the crisis of the late Qing. Daniel’s respect for China had sharp limits, however. He had come not to celebrate China but to change it. A conviction that China needed to be changed was far more than a Western notion or a missionary conceit. As most capable Chinese observers themselves recognized, traditional imperial governance no longer worked. Over-population and insufficient food sapped China’s strength and left it vulnerable to external pressures. The 19th century had brought the West more progress and improvement than in the previous millennium. But it had brought China one calamity after another. China proved unable to arrest its economic tailspin or to maintain itself in the face of rapidly advancing Western and Japanese military power. The missionaries believed the Christian Gospel would awaken China from its torpor. They did their best to alleviate the manifold human hardships entailed by an intensifying whirlwind of revolution and war. They witnessed the arduous and painful birth of a modern nation—a process that would be protracted across the entire 20th century. In December 1995, exactly 100 years after Daniel first arrived in China, Betsy and I were teaching at Beijing’s Foreign Affairs College. Anita and Sarah joined us for Christmas. A steady stream of friends paraded through our festive apartment. It was decorated with a potted evergreen tree, temporarily borrowed from the college gardens and lugged upstairs by four husky young students. How might Daniel have reacted to all of this? Without a doubt, he would have been bewildered by modern Beijing. A century before he had considered Shanghai hopelessly commercialized and ill-suited to receive the Christian message. China’s breakneck development since 1995 would have left him even more disoriented. On the other hand, he surely would have applauded China’s vastly improved food supplies, living standards, life expectancies, and literacy rates. He thought the people of China would draw the world’s attention if they ever got the opportunity to develop their talents. Daniel would have been especially gratified to find that the belief system so central to his own outlook has attracted many more Chinese followers than in his lifetime. Christians—flying under the disapproving radar of the Chinese state—have made the church their own. For them as for him, material well-being cannot fill the emptiness in the human heart. Daniel Crofts is professor of history at The College of New Jersey, the author of Upstream Odyssey: An American in China, 1895-1944, and most recently has written a series of articles at the New York Times Online about the origins of the Civil War.

|

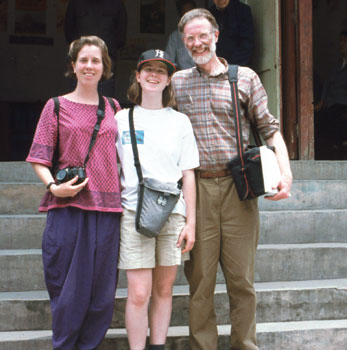

In May 1993, my two daughters and I stepped down from the train at Zhenyuan (JUN-you-en, literally “far-away town or outpost”), which clings to a riverside beneath steep cliffs. Anita, who speaks Chinese, masterminded this trip. Sarah and I were fortunate to have her as a guide. We walked across the 500-year-old Zhusheng bridge and gawked at the captivating scenery. Then we encountered Zhenyuan’s small Christian community, a group whose existence we had never suspected.

In May 1993, my two daughters and I stepped down from the train at Zhenyuan (JUN-you-en, literally “far-away town or outpost”), which clings to a riverside beneath steep cliffs. Anita, who speaks Chinese, masterminded this trip. Sarah and I were fortunate to have her as a guide. We walked across the 500-year-old Zhusheng bridge and gawked at the captivating scenery. Then we encountered Zhenyuan’s small Christian community, a group whose existence we had never suspected. I immersed myself in books about Chinese history. It was one thing to get outside my comfort zone and learn about the 19th-century American South. The learning curve was steeper for China. Happily, my wife Betsy and I were able to arrange a sabbatical year in 1995-96 teaching at the Foreign Affairs College in Beijing. We befriended many gifted young Chinese students, born near the end of the Maoist era and eager for greater opportunities than their parents had known. They taught us much about the country that had become Daniel’s home.

I immersed myself in books about Chinese history. It was one thing to get outside my comfort zone and learn about the 19th-century American South. The learning curve was steeper for China. Happily, my wife Betsy and I were able to arrange a sabbatical year in 1995-96 teaching at the Foreign Affairs College in Beijing. We befriended many gifted young Chinese students, born near the end of the Maoist era and eager for greater opportunities than their parents had known. They taught us much about the country that had become Daniel’s home.