Substantial Power |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

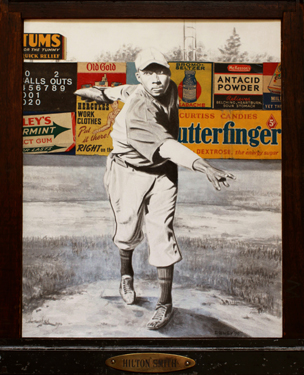

They say the piece “brings to life a tremendous talent” who was as overshadowed by his teammate Satchel Paige as Negro League baseball was overshadowed by Major League baseball. “Just as the Negro Leagues were part of the silent history of the United States, so Hilton himself was a secret,” the judges wrote. “Bringing him to life in the way that Dewey does is a tremendous accomplishment. This is an outstanding contribution to American art and significantly betters our visual understanding of Negro League history.” Such art may seem an imaginative stretch for a white art teacher raised in rural Pennsylvania. But sit down with Phil Dewey at his home in Ann Arbor, Michigan and you discover that the deep respect and empathy his work reveals for these men and their “silent history” is both hard-won and genuine. After Wabash, Dewey earned his M.F.A. in painting from Brooklyn College and taught art and music appreciation in New York City and New Jersey high schools from 1992 to 2005. He immersed himself in the culture of his students. “I was jazzed by New York,” Dewey says. “What I ended up doing was getting into teaching, not just to know the area, but to know the people. “I was teaching and hooking this up—the culture of the city, particularly black culture, that was an incredibly new experience. I didn’t do a lot of art. But I had picked up the guitar and blues in grad school—players like Robert Johnson, Skip James, Son House. My students were completely into hip-hop, so I introduced them to jazz and blues to show them the roots of their contemporary music. I was so into it that one day one of the students yelled out, ‘If I have to listen to any more blues music, I’m gonna go crazy!’ But I think I gave them something many of them hadn’t heard before.” He doesn’t remember where he found the postcards of some of the famous Negro League players, but the first he painted was James “Cool Papa” Bell, one of the fastest men to ever play the game. “The more I got into it, the more I realized there was this interesting part of American history I’d completely missed growing up,” Dewey says. Watching Ken Burns’ documentary Baseball on PBS, Dewey was captivated by the episodes about the Negro League players. “Burns was doing exactly what I was thinking about doing, but in a different medium. He said he had met his new hero doing the project—Jackie Robinson. Robinson became his new standard of what it means to be a man, a human being.” Dewey felt much the same way. “I was seeing some of the same challenges facing the kids I was teaching. Kids facing a lot of adversity. Poverty. Kids taking the train, or the ferry, for an hour just to get to a school that was safe. And this was the 1990s. “What I was painting was history—I was looking at this history through the lens of these students’ lives.” One of those students told Phil that the custodian at his middle school had been in the Negro Leagues. He showed up for class with an autographed postcard of the man and gave it to Phil. “I don’t want to take it, that’s a piece of your history,” Phil told the student. But the young man insisted. “He said he respected what I was doing,” Phil recalls. “That meant a lot to me. That added even more steam to the work.” Converging Legacies Dewey’s Negro League pieces are as notable for their craftsmanship as they are for Phil’s skill as a painter. He says the way he frames and assembles the pieces harkens back to three mentors. Dewey’s grandfather was a shop teacher. Phil was raised by his father, Tom Dewey ’58, who left a public relations job to become a cabinetmaker, in part, “to be able to stay home and keep an eye on me.” “In a lot of ways I think this work was what he wanted to do,” Phil says. With his father and grandfather both craftsmen, “I spent a lot of time in wood shop,” Phil says. “And I was always encouraged to do what I wanted to do.” The teaching and work of sculptor, photographer, and Wabash College Professor Doug Calisch inspired Dewey’s use of found objects. “I’ve gone from strictly painting to a combination of woodworking and painting on found objects. Sometimes painting gets boring and I need to get dirty, get some sawdust in the air, do some work that makes you have to take a shower, not just clean paint off your hands. “The physicality of my father’s and grandfather’s work carries over in me.”

|

The judges who named Phil Dewey ’89 the 2010 winner of the Jerry Malloy Competition for Outstanding Negro League Art call his portrait of Kansas City Monarchs pitcher and National Baseball Hall of Famer Hilton Smith “a small piece with substantial power.”

The judges who named Phil Dewey ’89 the 2010 winner of the Jerry Malloy Competition for Outstanding Negro League Art call his portrait of Kansas City Monarchs pitcher and National Baseball Hall of Famer Hilton Smith “a small piece with substantial power.”