A Man's Life: Sad Menby Jason Boog |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

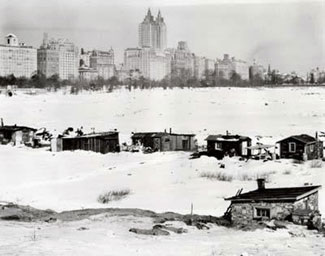

An ongoing conversation about what it means to be a man in the 21st Century I lost my job in December 2008, unemployed at the beginning of the longest, coldest winter I can remember in New York City. Up until then, everything had been going swimmingly: I was a staff writer at an investigative reporting publication, taught an undergraduate journalism class, and proposed to my girlfriend in a fairytale forest along the Hudson River. Suddenly, I had to tell my friends, relatives, and students how I had failed. Out of everything I read during those gloomy months, I found the most comfort in Maxwell Bodenheim—an author who lost everything during the Great Depression. In 1934, he wrote: “There’s something wrong with this world all right, but I can’t put my finger on it…Something must be wrong when a fellow can’t get a decent wage, can’t tell when he’s going to be fired, can’t look forward to any promise of happiness. Something is rotten somewhere.” Reading those lines, I felt like somebody had finally described my New York City predicament. As I struggled to find work, I contemplated Bodenheim’s generation—hoping to find some clue to how they survived economic disaster. I collected stacks of clippings and a bookshelf of abandoned books. Following their footsteps, I traced an invisible map of New York City’s most miserable landmarks. Somehow, the project soothed me. My journey began in Washington Square Park. All winter long, construction crews remodeled the frozen grounds, the community space crowded with hurricane fence and machinery. Bodenheim’s career revolved around this corner of the city. During the Roaring Twenties, they called him the King of the Greenwich Village Bohemians, and he published a stream of novels about boomtown New York. I found a picture of him surrounded by scantily clad showgirls and holding his bestselling novel like a trophy. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Bodenheim lost it all. .jpg) By 1936, a New York Times article found him peddling poems for 25-cents apiece. The newspaper reporter parodied his sorry group selling poetry in the park: “Once more the sturdy fence at Washington Square South and Thompson Street bore its burden of handwritten, typed and mimeographed sheets. The occasional thud of a tennis ball on the inside of the enclosure was a disconcerting novelty, but otherwise the sound effects were merely the gay, chattery, wistful comments of poets on parade.” By 1936, a New York Times article found him peddling poems for 25-cents apiece. The newspaper reporter parodied his sorry group selling poetry in the park: “Once more the sturdy fence at Washington Square South and Thompson Street bore its burden of handwritten, typed and mimeographed sheets. The occasional thud of a tennis ball on the inside of the enclosure was a disconcerting novelty, but otherwise the sound effects were merely the gay, chattery, wistful comments of poets on parade.”The tennis courts are gone, but artists of all stripes still struggle to earn cash in the park all year round: break dancing crews, jazz trios, and a kid with a battered typewriter who pounds out poems on demand. Sitting there, I could still imagine rows and rows of poems taped, tied, and stuffed into the fence, flapping like prayer flags—as close to Bodenheim as I could get. Exploring the slushy city, I began to notice the shelters and soup kitchens scattered around me. Contemporary recession victims visit the Salvation Army and Bowery Mission that stand side-by-side on Bowery Street —two Lower East Side landmarks that housed homeless men during the Great Depression. A struggling newspaper reporter named Edward Newhouse wrote about these places during the 1930s. In his novel, You Can’t Sleep Here, Newhouse described an overcrowded Bowery shelter: “More half-naked and naked men crowded through from other rooms. The flophouse stench of filthy bodies, filthy clothing and breaths of disordered stomachs closed in, and there was no shaking it…Most of the men had coughs of one sort or another. There wasn’t a moment when two or three weren’t clearing their throats. Putrefaction was in the air.” Newhouse wouldn’t recognize the Bowery anymore. Two blocks north of the mission stands an enormous Whole Foods store selling organic goods at luxury prices. The mega-store is bracketed on all sides by shiny new condominiums built during the housing market boom. As New York’s unemployment climbed towards 10 percent, these glass castles seemed like relics from a different world. This year, I watched Mad Men on television—the AMC drama following the decadent lifestyles of New York City advertising executives in the early 1960s. I wondered how anybody in our world could relate to that prosperous period. The show explores the suburban landscapes chronicled in books by John Updike and John Cheever, the middle-class scribes who wiped Bodenheim’s generation off the literary map. Those writers couldn’t help me last winter. Instead, I gravitated to a bunch of Great Depression misfits who endured the same problems that we face now. I called them Sad Men. That same winter, I witnessed a group of fresh-faced Christian missionaries struggling to convert a moody crowd at Union Square in Manhattan. Despite the cold, the park had collected a crew of unemployed workers, homeless people, and bored teenagers. I could feel frustration and anger simmering around me, channeled towards these misguided evangelists. I was frustrated, too. As the winter dragged on, I managed to find some freelance assignments, but full-time work was scarce. All around me, writers were losing their jobs at a record pace: According to the layoff tracking Web site Paper Cuts, nearly 16,000 journalism jobs were lost in 2008 and another more than 13,000 have been lost in 2009. As I applied for new jobs, I could feel the invisible pressure of those statistics—a single entry- level journalism job could draw 1,000 applications. Economic impotence drove a number of Depression-era writers to radical politics. Novelist Edward Dahlberg channeled Depression despair into white-hot rage. His 1932 novel From Flushing to Calvary records a brutal police crackdown on a Union Square protest. Dahlberg wrote: “Scuffling, shrieks, horns, motorcycles went sirening through him with the nightmare gallop of a fire engine…opening one eye, he saw the anthill parade crowd, splintered, flying off in all directions…over him three sky-blue uniforms were kicking a man in the stomach. A woman, her hanging hair shrieking and spurting over her eyes in fingernail scratches, was punching out and pummeling, yanking with insane fingers the brass buttons off their coats.” During the 1930s, Union Square was a hub for radicals of all stripes. Dahlberg, Newhouse, and Bodenheim all supported radical movements during those tumultuous years. They all witnessed protest marches, strikes, and riots rise up in this communal space. Despite our recession, Union Square is peaceful now—except for the occasional politician or Christian with a microphone. Even though we face some of the same economic inequalities and rising unemployment, we don’t have any of the political fury that drove many writers to support radical solutions during the Great Depression.  In 1931, the city drained a Central Park reservoir, leaving behind a sandy, boulder-strewn field where homeless congregated throughout the Great Depression. Newhouse actually lived in a New York shantytown for a few weeks, and half of You Can’t Sleep Here is set in the Central Park slum. He describes one of the shacks: “It was built of three billboards and a boulder and it had a strip of linoleum on the ground and gunny sacks.” In 1931, the city drained a Central Park reservoir, leaving behind a sandy, boulder-strewn field where homeless congregated throughout the Great Depression. Newhouse actually lived in a New York shantytown for a few weeks, and half of You Can’t Sleep Here is set in the Central Park slum. He describes one of the shacks: “It was built of three billboards and a boulder and it had a strip of linoleum on the ground and gunny sacks.”To complete my New York City journey, I went back to find the place where Shantytown stood. According to a 1930s guidebook, the slum lay in a field at the exact center of the park, as far from the hum of traffic and the wall of New York City rooftops as you can get inside the city. The city razed the tent city near the end of the Depression and developers landscaped the spot into a gorgeous oval of grass ringed by rows of baseball fields—part of Central Park’s magnificent Great Lawn. A plaque near the Great Lawn commemorates the 1930s renovation, but doesn’t mention that Shantytown used to stand there. New York City carefully rehabilitated all the bad memories and gloomy places where the Sad Men used to live. Americans don’t like to dwell on failure. As soon as the economic crisis passed, literary scholars abandoned these novels from the 1930s. Bodenheim spent the rest of his life in and out of flophouses, and never wrote another novel. Both Dahlberg and Newhouse went on to have careers as writers, but their 1930s work hasn’t been reprinted. The last scholarly book I found analyzing the Depression-era novels of Bodenheim, Dahlberg, and Newhouse was published over 50 years ago. Since that gloomy December, I’ve married my fiancé and found freelance work, but I’m always scrambling to pay next month’s health insurance. Things won’t improve anytime soon—it took 10 years and federal government initiative to put writers back to work during the Great Depression. As I was finishing this piece, the publisher Condé Nast shuttered four magazines with a single memo, including the 68-year-old Gourmet. I’m afraid the days of glossy magazines and full-time writer jobs have passed, unraveling our old value system for the writer’s work. Meanwhile, we keep these Sad Men buried in the literary rubbish heap, despite the fact we need their stories now more than ever—because nobody builds monuments to failed men. Jason Boog is an editor at mediabistro.com’s publishing Web site, GalleyCat (www.mediabistro.com/galleycat). His work has appeared in The Believer, Granta, Salon.com, The Revealer, and Peace Corps Writers, and he is a contributor to the Poetry Foundation’s poetryfoundation.org

|