WM Winter 07: Faculty Notes |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

Extraordinary Hospitality

Lucinda Huffaker created safe space for brave conversations at the Wabash Center.

But they also came to thank its director, Lucinda Huffaker.

For one moment, the woman who for 10 years has made so many others feel honored, safe, and empowered to talk about the things that matter most to them was herself the guest of honor. They presented her with a beautiful print of the Gospel of Luke frontispiece from the St. John’s Bible. The person who had encouraged so many to speak didn’t know what to say.

But the standing ovation from colleagues from across the country spoke volumes about the impact she has had as director of the Wabash Center. The genuine admiration shown by those she has served was also a fitting farewell, as Huffaker left the Center in December 2006 to pursue other projects.

The Summer 2007 issue of Teaching Theology and Religion will pay tribute to Huffaker and the Wabash Center in a series of articles by several authors, including one by Wabash Professor of Philosophy and Religion Bill Placher ’70.

An edited excerpt:

Very early in the life of the Wabash Center, its founding director Raymond Williams made two important decisions. He identified hospitality as a key virtue of the new institution, and he hired Lucinda Huffaker as its first associate director. What no one could know at the time was how closely related those two decisions would turn out to be. During her six years as associate director and four years as director, Lucinda has been both the principal symbol of and the principal force behind the Center’s reputation for extraordinary hospitality.

At the core of the Center’s work lie the convictions that teaching is important, that reflection on teaching can make teaching better, and that the best reflection on teaching takes place in a context of mutual honesty and trust. Those convictions are, in practice if not in theory, sufficiently countercultural in the academic world today that one needs consciously to make a space for them, and hospitality is one way of doing that.

When people come to conferences at the Wabash Center, a spirit of hospitality serves other functions, too. Talking frankly about teaching, we have discovered, does not come easily. Many young faculty members suspect, often rightly, that it will not be safe to talk with colleagues at their home institutions about their problems in teaching.

Emboldening people to take such risks is one of the functions of hospitality. Hospitality in discussion manifests itself in making oneself vulnerable in ways that signal it is safe for others to make themselves vulnerable, too. It seems to me that a bit of a miracle happens in most Wabash Center workshops. When a group of strangers gathers one day and by the next is speaking passionately to one another about things that matter deeply, confessing failures, laughing, sometimes crying. How did they come to know that it was safe to do that? Henri Nouwen has written that hospitality is the "creation of a free space…. Hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place."

The Wabash Center’s staff has had a gift for creating that kind of space.

So from the beginning staff members have defined their roles as "servants of excellence." They would not set themselves up as the experts who could tell participants how to do things right, but as facilitators who would help smart, thoughtful, passionate faculty members find their own answers about why teaching is important and how to do it well.

Another of Lucinda Huffaker’s particular gifts has been to recognize the importance of play in creating an atmosphere of hospitality. Volleyball, canoeing down Sugar Creek, or jumping rope have become a part of nearly every workshop. Most of us think we are very good scholars and teachers. Most of us recognize that we are not that gifted at sports (though unexpected talents do emerge); our egos are not here much invested. Thus the late afternoon spent playing a game where most of us are fairly incompetent makes it easier to admit the next morning that we are not always altogether competent as teachers either.

The staff of the Wabash Center has created a welcoming environment of Christian hospitality, making a safe space in the academic world. Without that space, the brave and productive conversations that go on at the Wabash Center would not have been possible, and no one has contributed more to the spirit behind all this than Lucinda Huffaker.

Campus Quotes

The lodgepole pine produces two different kinds of pinecones. The non-serotinous cone is open. The seeds release easily. The serotinous cone is closed. The only way a serotinous cone will release its seeds is in the event of a forest fire.

Now, most right-thinking people would be content to appreciate this marvel of nature. But as a writer addicted to metaphors, I had to go and impose one on the lodgepole. I wondered about a human brand of serotiny, about a kind of tightness or remaining closed to change so that only the most extreme adversities, when our very survival is at stake, can make us open.

It is so easy to be closed. So tempting. There is so much to preoccupy us, to consume us, so many things to desire and consume, so much work to do just to care for our own economic bottom lines, so much positive social reinforcement for doing so. And what we hear about global warming and climate change and increasing hurricanes and tornadoes and melting polar ice shelves and dying coral reefs can feel so overwhelming that it can cause a kind of hopelessness, helplessness, a kind of despair. We can retreat into ourselves and our small, controllable pleasures and ambitions.

Like Baldwin on issues of racial justice, I believe, regarding environmental justice, that "for the sake of one’s children, in order to minimize the bill that they must pay, one must be careful not to take refuge in any delusion." I fear we cannot run the risk of conflagration. I want us to be ahead of the curve, to anticipate ecological disaster, and head it off with innovative, compassionate, creative, equitable solutions. I want to understand now what factors make some people, without facing immediate personal threat, open themselves to social justice and environmental care, and I want to develop ways to implement those factors gently, steadily, deliberately, and wisely. Without incineration.

—from "Notes Against Serotiny," the 27th Charles D. LaFollette Lecture, by Associate Professor of English Joy Castro

Faculty Bookshelf

Excerpts from recent publications

Freeing the Angry Mind

How Men Can Use Mindfulness and Reason to Save Their Lives and Relationships

—by C. Peter Bankart

Angry men drop dead.

No, this isn’t a command! It’s a simple statement of fact. Anger releases a cascade of hormones in your body that activate a series of circuits in your brain which make you unable to think clearly and which command your muscles, organs, and digestive processes to quit what they are doing and prepare to go to war. When your body does this repeatedly you become emotionally and physically exhausted. And when you continue to repeat this process while in a state of exhaustion, you start doing serious damage to yourself. Do it long enough and you will die.

Anger literally kills men. It destroys their cardiovascular system. It wrecks their immune system. And it effectively blocks the most important natural system that helps them recover from prolonged or excessive periods of hyperarousal.

Especially in men, anger and depression are biologically and psychologically almost the same thing. Often, therapists working with depressed angry men can’t draw a line between where the anger ends and the depression begins, or vice versa. As Phillip Martin observed in this 1999 book The Zen Path Through Depression, when we are ill with depression, we are literally sick with anger.

Peter Bankart is a professor of psychology at Wabash. Contact him at bankartp@wabash.edu

Dylan Redeemed From Highway 61 to Saved

—by Stephen H. Webb ’83

In the late 70s, evangelicals like me needed a musical hero who could speak to the disturbing chasm that separated the harmony of Sunday morning from the discord of Saturday night. We wanted a sonic power to match the depth of our experience of salvation, but we also just wanted to listen to rock and roll with a clean conscience. In my Midwestern evangelical home, rock and roll was treated like an unwelcome guest who showed up late, loud, and drunk during times of family strife. Inevitably, my dad would have to ask him to leave. Now the greatest rocker of all time was one of us.

I became a fan, eagerly awaiting each new album, but it took me years before I was ready to listen to Slow Train Coming again. That album took me back to my evangelical youth too quickly and too forcefully. When I finally played it again in the late 90s, it took my breath away and left me gulping for air. It was as if the apostles had come back to life and were putting the day of Pentecost to music.

To some, the album sounds preachy and pious, but that was not my problem. To me, it sounds painfully honest and true. Slow Train Coming convicts my conscience with the sound of a faithful purity that I am too often able to muster with the same enthusiasm. It sets me dreaming of what I know faith can and should be. That album is and always will be what faith sounds like to me. I could no more turn my back on it than I could turn my back on the faith of my youth. Coming to terms with it meant looking in the mirror of Dylan’s music for something more than his enigmatic personality or even my own spiritual journey. It meant looking for the acoustical shape of salvation.

Steve Webb is professor of philosophy and religion at Wabash. Contact him at webbs@wabash.edu

What is Military History?

—by Stephen Morillo with Michael Pavkovic

The root of the disrespect, however, most lies in its subject: war. There exists a deep suspicion that to write about war is somehow to approve of it, even to glorify it—a suspicion not unfounded in the history of the writing of military history.

But to recognize the importance of a subject in the study of the past does not mean approving of it, as any historian of the Holocaust will attest.

Military history today is practiced by as broad a range of historians, in their political, ideological, and methodological interests, as any other branch of history, and in both its topics and its methods lies solidly in the mainstream of historical study.

In most places, by the time writing was invented there were already kings and armies. It did not take long for kings to recognize the value of the new communication technology in publicizing and thus glorifying their exploits. Military victories proved especially useful for such publicity. Even more powerfully, the image of a war leader as presented in writing and pictures spoke directly of the very qualities most likely to enhance a ruler’s reputation. A ruler with a good military publicist appeared favored by the gods.

Military history is therefore the oldest form of historical writing in many cultures.

Steve Morillo is professor of history at Wabash. Contact him at morillos@wabash.edu

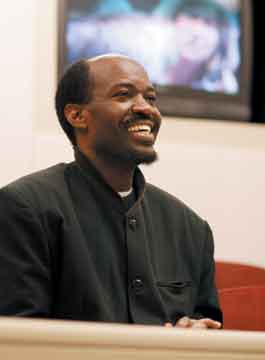

Musical Healing

During an hour-long videoconference in October linking Wabash students and staff with doctors from Mater Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya and the University of Florida, the teacher and music therapist led a discussion exploring "the role of the arts in health care today and how we might integrate the arts into health care in the 21st century."

Professor Akombo’s book, Music and Healing Across Cultures, was the springboard for the discussion. Akombo spent three years researching the musical rituals of the Taita people of his native Kenya and the Balinese people of Indonesia.

"In Kenya and Bali, I have seen and documented healing rituals in which singing and dancing were used to help patients recover," Akombo told the group. "I want to see if these results can be quantified, and I hope this partnership can provide that."

Professor Akombo’s work was also featured in articles in the Gainesville Sun and The Standard of Kenya.

"The courage to become stronger"

Will the National Study of the Liberal Arts be a catalyst for making Wabash even better?

More students than ever are attending college, yet public skepticism regarding higher education persists.

"We’re at a crucial point in the history of liberal arts colleges," says Wabash Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts Director Charlie Blaich. "Can we learn from each other? Will we have the courage and will to become stronger, to do better by our students?"

Blaich believes the answer must be "yes" and that the Center and its National Study of the Liberal Arts will be a catalyst. Comprising 19 colleges and universities and institutions as varied as Hope and Hamilton colleges and Notre Dame and the University of Michigan, the study was launched in 2006 and preliminary results will be released this fall.

A 60-institution applicant pool and the enthusiastic embrace of the study by the participating institutions has the often understated director and social scientist using words like "amazing" and "inspiring."

WM checked in for an update.

WM: What will the study be looking for?

Blaich: We’ll be looking for the impact that colleges and universities have on students’ moral reasoning and character, critical thinking, inclination to inquire, intercultural effectiveness, leadership, and well-being. We want to know when, how, and in what contexts these qualities develop.

It’s not about proving whether one institution is better than another; it’s about finding out what works for different kinds of students at different kinds of places.

The sheer diversity of liberal arts colleges would seem to make them a difficult group to research.

Liberal arts colleges are different, quirky; they haven’t been homogenized by state regulations. That’s one of their strengths. You can have St. John’s College on the one hand, and Evergreen State College on the other, with very different curricular structures, grading systems.

The idea is not to rank and sort these schools, but to find out the conditions that help create these outcomes. Also, what are students choosing to do to bring about these outcomes? They’re hardly passive in all this.

You sound excited to see these results.

In the last couple of years I’ve had the chance to visit all sorts of institutions around the country. I’ve sat in on faculty workshops, curriculum meetings. These visits have had a strong impact on me. It’s simply amazing the range of interesting things that faculty and students are doing. It’s inspiring.

And the institutions we’re working with see the study as a way of strengthening themselves, a way to find the strengths and weaknesses of their institutions. They are excited to learn if we can use this data to help their students. It’s gratifying.

Why is the study essential to Wabash?

Faculty and staff here think a lot about how to make Wabash better for students. This study provides more information for that process. It can enhance our thinking about how to make Wabash better for students and faculty.

Data can surprise you. For instance, I’ve long thought that Wabash students can’t synthesize the knowledge gained from our required distribution courses, but I’ve been looking at some interviews that David Blix recently completed, and I’ve been surprised both at how and in the interesting ways that our students are pulling things together.

There are also cases where we assume something is happening with our students in and out of the classroom, and this study may tell us it’s not happening. That can help you ask the next question.

For instance, we have students in our offices all the time here. But what about the students we don’t see, who for whatever reason, hold back? Data like this can at least prod us to consider these things and how to improve and perhaps reach those students.

Expect any other surprises?

We’re interviewing 50 students from Wabash every year, and when we ask, "What has had the most impact on you this year?" I think many faculty members will be surprised by what we hear. I think we’ll find that later in their undergraduate careers, students interpret many stressful events, like dealing with difficult roommates, choosing a major, or even something as traumatic as a sports injury, as important, even character-building moments.

One of the biggest challenges will be getting information from the study into the hands of faculty in a way they can use the information.

Another challenge will be to see if we can help liberal arts colleges work constructively with one another. One of the functions of the Center is to be a catalyst for that. Can we see what unites us, see our common problems, and perhaps pool our resources to improve?

What’s in it for Wabash?

Dean of the College Gary Phillips says the work of the Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Art s is the work of Wabash College. He sees Wabash gaining a great deal from the National Study, even as the study learns a great deal from Wabash.

"The study offers the possibility that we can clarify what it is we do here that works, what doesn’t work, and how we can move in the direction of the former as we make curricular and institutional changes," Phillips says. "And as we talk to all of the publics of the College, the study offers us the opportunity to not simply hype what we believe, but to communicate what we know we do for students here."

The study comes at a crucial time; the College is immersed in an academic program review and strategic planning.

"Add the demographic changes affecting faculty hiring and retention, society demanding that colleges show evidence of what they can do, and the national conversation about the crisis in men’s education and the status of men in the country, and you see these converging forces that the Wabash National Study can help us to address and navigate."Phillips is encouraged by recent efforts by the faculty teaching and learning committee to embrace aspects of the grant that established the Center.

"The discussion of teaching and learning that continues to grow among an increasing number of faculty is an indication of the heightened degree of self-reflection in the College, and that is paralleling the progress of the National Study," Phillips says. He recalls a recent gathering of faculty during which Professor Blaich explained the details of the National Study.

"There was an animated discussion among faculty eager to know more because they realized the results of the study are about Wabash students, the young men they work with every day," Phillips says. "Suddenly the study was not just about curriculum, or college hype, but about these particular human beings we’re teaching here right now."

Phillips believes one great benefit of both the Center and the study is its role as "a constant reminder of the need we have to interrogate and become self-reflective.

"We need an attitude of interrogation that asks, ‘What is it that we’re not thinking about here?’ Phillips says. "We can be mesmerized by looking at data like the College’s scores in the National Study of Student Engagement, which puts us in a sort of pantheon of best practices. But unless we’re suspicious in our interrogation, we might assume that study speaks for all Wabash students. That’s not the case. We need to learn who’s not being spoken for in that study.

"Our work with the National Study can make that possible," Phillips says. "That’s good news, but it’s hard news. It’s good because we’re extending to the institution’s mission the same level of self-critique we expect of our students and faculty. It’s hard because it also exposes where our practices are not the best.

"It takes a certain degree of courage to say, ‘This is what we need to be doing better.’ And that’s not a failure. That’s exactly what the liberal arts critical experience is all about—figuring out how to do it better. And Wabash benefits in an extraordinary way by the Center’s work in being a constant reminder and helpmate in that level of self-reflection."

|

When nearly 500 Wabash Center workshop participants and grant recipients gathered in Washington, DC for a reception during the world’s larg-est meeting of biblical scholars and theologians, the stated aim was to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion.

When nearly 500 Wabash Center workshop participants and grant recipients gathered in Washington, DC for a reception during the world’s larg-est meeting of biblical scholars and theologians, the stated aim was to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion. "The culture we live in treats men’s anger as normative. Boys learn early on that displays of anger are considered manly and are exceptionally effective in covering up a huge range of emotions. A man may go through several relationships and untold suffering before it occurs to him that being angry all the time is not a sign of his advanced masculinity but evidence of a serious (perhaps literal) hole in the middle of his heart."—Peter Bankart

"The culture we live in treats men’s anger as normative. Boys learn early on that displays of anger are considered manly and are exceptionally effective in covering up a huge range of emotions. A man may go through several relationships and untold suffering before it occurs to him that being angry all the time is not a sign of his advanced masculinity but evidence of a serious (perhaps literal) hole in the middle of his heart."—Peter Bankart I graduated from high school in 1979 and I knew next to nothing about the way Dylan had transformed rock by making it sound poetic and had alienated folk audiences by playing loud and hard. But the rumor that Bob Dylan had been saved struck my ears like a thunderbolt from the sky. And when I listened to his first Christian album, Slow Train Coming (1979), I heard the gospel proclaimed to my heart in a way that finally made sense to my ears.

I graduated from high school in 1979 and I knew next to nothing about the way Dylan had transformed rock by making it sound poetic and had alienated folk audiences by playing loud and hard. But the rumor that Bob Dylan had been saved struck my ears like a thunderbolt from the sky. And when I listened to his first Christian album, Slow Train Coming (1979), I heard the gospel proclaimed to my heart in a way that finally made sense to my ears. Military history is not the most respected branch of historical inquiry in academic circles. In part, this is because of (and despite) its popularity with the general public and its importance in educating professional military personnel.

Military history is not the most respected branch of historical inquiry in academic circles. In part, this is because of (and despite) its popularity with the general public and its importance in educating professional military personnel. Visiting Assistant Professor of Music David Akombo brought not only his musical gifts to Wabash, but Kenya and the University of Florida, as well.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Music David Akombo brought not only his musical gifts to Wabash, but Kenya and the University of Florida, as well.