|

THIS IS NOT WHAT YOU WANT TO HEAR; these are details you don’t want to know. THIS IS NOT WHAT YOU WANT TO HEAR; these are details you don’t want to know.

"I see the world differently than you," 14-year veteran Chicago firefighter, counselor, and employee assistance coordinator Dan DeGryse ’86 says. "You have to choose: Do you want to look through that window?"

IN OCTOBER 2001, the view was Ground Zero—16 acres of death in the heart of New York City. DeGryse and other counselors from across the country flew to New York to provide counseling and support for firefighters and policemen who had just lost 343 of their own to the September 11 attacks. Men and women whose vocation was to save lives were dragging pieces of bodies from beneath tons of debris. The counselors’ mission was an unprecedented effort to offer emotional and moral support to workers

facing untold horrors.

"It was a spontaneous field debriefing," DeGryse says. "We’d go up to the rescue workers and try to interact, look at their demeanor, their eyes. We’d offer them something to eat or drink and just see how they were doing; say a few words, see if they needed to talk it out."

Though his focus was the workers, DeGryse couldn’t help but be affected by their work.

"Ground Zero was a pile of bodies. A morgue. I walked around it probably a dozen times over four days. Some-times these workers would dig and find body parts. I’d see an arm in one place, a leg in another, an eyeball or something there."

Yet those aren’t the images that most haunt him.

"Most people experience their highest anxiety point when they’re in a crisis, but we’re programmed the complete opposite," DeGryse says of himself and his firefighter colleagues. "I am most calm when handling a problem. When everyone around me is chaotic, I’m conditioned to maintain calm—that’s what most firefighters are like."

Calm, but not unfeeling. And the emotions rose in quiet moments, when his guard was down.

At 3 a.m. during one of his rounds, DeGryse asked a rescue worker what he’d found toughest to deal with. The man pulled out his cellphone.

"I’ve got 30 names in my phone that I have to erase," the man said.

"This guy was 32 years old," DeGryse recalls, "How could he ever expect to lose 30 friends in one day?"

Tragic ironies overwhelmed minor miracles.

"I talked with a medic whose friend, also a medic, had rushed to Ground Zero when the first tower collapsed, knew his girlfriend was in the second tower, so went inside to rescue her just before that second building came down," DeGryse says. "It turned out that his girlfriend was already outside, in an ambulance. But he never came out.

"We went to half a dozen funerals for [firefighters] in four days. You couldn’t imagine the depth of grief those people were feeling—to have lost loved ones at such an early age," DeGryse says. "And there had to be 1,500 people at each funeral—343 firefighters and policemen died, and so many more lives were scarred by this."

After DeGryse returned from New York, he saw a photograph of Ground Zero in Wabash Magazine and was angered.

"When I was there, I’d see people taking pictures and I’d ask them, ‘Would you take pictures of a morgue?’" DeGryse says. "To some, this was a spectacle of destruction. But what I see are dead bodies, families being ruined, and families being ruined in the future because grieving friends or family members will never be the same—they’ll start drinking, or doing drugs, or lose their jobs.

"The counseling center for New York’s employee assistance program (EAP) used to handle about 300 cases per month—it jumped up to 1,600 in the first month after 9/11," DeGryse says. "And those were just the ones willing to talk—they were the lucky people who said, ‘I’m going to get this addressed.’ In the firehouse in the beginning, these were probably looked upon as the weak ones; ostracized as ‘going to the nut farm.’ But a lot of those others just quietly retired and said, ‘I can’t take this anymore.’

"This thing didn’t end on September 11, or the next month, or the next year. For many, it’s a very present tragedy."

DEGRYSE SEES HIS EXPERIENCE at Ground Zero as a microcosm of the situation police and firefighters face every day. In addition to working his shift as a lieutenant in the Chicago Fire Department and his union’s EAP coordinator, DeGryse is on the staff of HealthNetwork EAP, which provides programs for private companies and other organizations. Still focused on working with public safety officers, he’s determined to help firefighters and police get the attention and counseling their work demands. Many firefighters are part-time or volunteers not eligible for the sort of counseling benefits available in larger cities but nevertheless facing the same tragedies.

Firefighters have one of the highest divorce rates when compared to other occupations. In his own firehouse, 9 of 12 firefighters have either been divorced or are going through it.

A recent Canadian study found 16% of firefighters suffered from post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD)—about 1% higher than PTSD rates from the Vietnam War.

That well-trained ability to handle crisis can be both a blessing and a curse.

"Other treatment professionals say firefighters are secretive and withdrawn," DeGryse says. "It’s like we’re different creatures, but the key is still communication. When people hold in communication, they get either physically or emotionally sick. That’s key for individuals, that’s key in almost all the marriages I’ve intervened in as a counselor.

"They have to understand that it is not weak to say what bothers you, but that it’s a sign of strength," DeGryse says. "Many in our parents’ generation found other ways to let it out—drinking, drugs, gambling, marital infidelity. Dealing with it that way was viewed as ‘tough;’ but that’s not tough—it’s really the weak way to handle it."

Such understanding goes against the grain of the old firehouse culture, but events like 9/11 have been a catalyst. DeGryse says the culture is beginning to change. That change doesn’t weaken the camaraderie of the fire service, but strengthens it. These are men and women bonded by a desire to serve in the face of tragedy. DeGryse carries his own dark memories:

"We pulled up to a fire where we’d been told there were two kids in the building," DeGryse recalls.

"But after five minutes in there, we couldn’t find the kids, and we couldn’t find where the fire had started.

"So we’re checking the only door left—a two-foot by two-foot linen closet—and the guy who’s on the hose forces the door open. I’m standing there with an axe and pike pole in my hands and what look like two child-sized dolls fall out of the linen closet. They had been locked in there by their grandmother, who had been watching the kids. She wanted to go to the store, the linen closet was the only room in the house that could be locked, so she put them in there and left.

"The kids had matches, a lit match fell, started the floor on fire, and burned them alive. People read about these things and say, ‘Ohmigosh,’ but we live it. We see it, and we have to swallow it and deal with it every day."

WHEN WM FIRST SPOKE with Dan DeGryse in 1998, he said he’d found in firefighting a job he truly loves:

"From the moment I wake up to the next morning when I come home, I enjoy every minute."

Ask him today if he still feels like a lucky man.

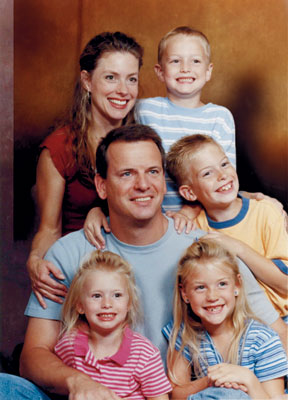

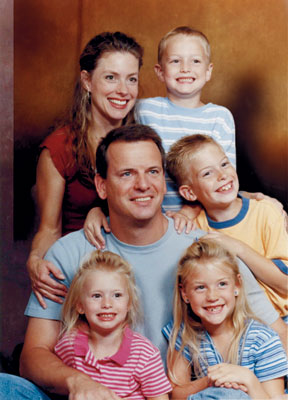

"I see these kids burned, marriages broken up, and the lives that have been lost through drinking or drugs—but I try to keep a positive outlook. I also see that I’ve been able to provide a nice home for my family, that I’m able to walk, talk, work three jobs, my kids are safe, and they’re good kids."

He’s most fortunate, he says, for his wife, Victoria. An excellent listener herself with a master’s degree in social work, she understands the value of communication in their relationship.

It’s a luxury many of his colleagues do not have.

"For me, every firefighter is a brother or sister," DeGryse says. "There are a lot of them out there who don’t have anyone to talk to about this stuff."

He’s working now to see that they get the attention, and, if necessary, the treatment they need. It’s work that asks us to see the world through his eyes now and then. Even if we’d rather not look.

Photo: Dan DeGryse with his wife, Victoria, sons Nicholas and Daniel, and daughters Samantha and Alexandra.

|

THIS IS NOT WHAT YOU WANT TO HEAR; these are details you don’t want to know.

THIS IS NOT WHAT YOU WANT TO HEAR; these are details you don’t want to know.