Maskby Abraham Lucas '05 |

| Printer-friendly version | Email this article |

|

At first it means next to nothing staring at you in the halls of the costume shop, but then comes the awareness that you have changed to the world.

Kay came straight to Athens from Norway after a semester in Oslo. She was a blonde. She had a carefree nature, a striking figure, and what I would come to understand as a provocative indifference toward the feelings of others. She was more than real. She loved carrying our 70-pound pack all weekend, and when I insisted on carrying it for a while, she was disappointed-not some feigned disappointment that quickly fades into acquiescence, but a real, push-you-in-the-dirt-and-yell "that's what you get for taking the pack" disappointed. She was undeniable. I was in real danger of losing myself in this girl.

Most of our compatibility as a couple came from the fact that neither of us ever held the other back. Each of us was a catalyst for the other. And a good thing, too, for Carnival was to be 72 hours of revelry that would put to shame the stamina of even the most memorable of my past fraternity festivities. The frat party is a thousand mayflies beating their dying bodies against the lethal burn of a porch light to the beat of a bass drum; Carnival was pure motion, and for a moment we were fooled into thinking that it might outlive us all.

The character of the five-day weekend became readily apparent when we got turned away from the doors of Club Medusa right around sunrise due to lack of space. It was Kay's element. When she quickly disappeared into a corner store, remerging with a bottle of Ursus Russian vodka, there was no debate, no hesitation. There was only drinking. When we stopped by the costume shop to get our masks and capes, there was no discussion, no trepidation.

Again, she was undeniable.

For that weekend, garish hats were in high fashion and the idea of a curfew was as foreign as the two white faces strolling side-by-side down the streets well-cluttered with beaming faces and hasty footsteps. It was to be a mutual indulgence of two very ambitious natures.

Interrupted only by a few scattered hours of dreamless sleep at a ten-euro hostel, there were long stretches of shameless, costumed parading through the streets, watching furious masked dancing on corners, in alleys, on bar tops and beachfronts. And then came the vans, gaudy vehicles which made meandering circuits about the city, bearing a makeshift stage and speakers slapped on their roofs, as if to make it official: Now had come the time for dancing atop moving vans. Even in my most reckless states I have never felt the urge to dance atop a moving vehicle, and yet there we were, like orchestra conductors towering above this endless crowd.

And then there was the mall courtyard converted into a dance floor, tables cast aside like winter coats in springtime to make room for bodies, encompassed by four stories of balconies brimming with dancers and revelers, all bound up in a time and place where you sweat and everything you touch sweats and there is sweat on sweat so thick and so careless it might as well have been raining.

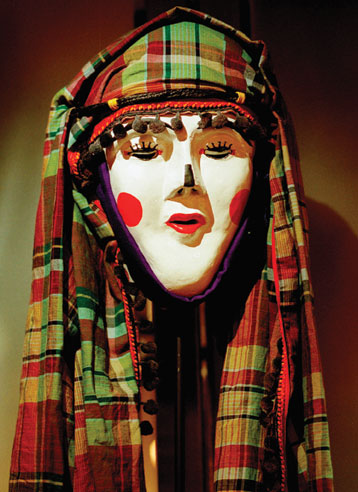

And everyone must wear a mask. That thin layer of glittering paper weighs a few ounces and at first means next to nothing staring at you in the halls of the costume shop. It means little more once it's found its way onto your face, for though things get hotter and you lose a little in the way of peripheral vision, the person inside remains essentially the same. But then, ever so gradually, there comes the awareness that you have changed to the world. You first detect it in the lingering stares of a few passers-by, in the coy, improbable smile of a pretty face casting glistening white eyes in your direction from beneath the shroud of a colorful paper mask. Then comes the physical closeness, contact becomes more careless; for once hips are swaying toward you instead of away. Something is different. Pause. Think. Epiphany.

And there it is—the awareness of your pure and blessed anonymity, not just freedom from recognition, freedom from every external judgment constantly weighed upon your appearance since the day you were born.

Suddenly you're free from the blonde hair, the brown eyes, the fair skin, and the bad Greek accent, all those things that collectively damn you every time you turn the street corner and have a face-to-face collision with those shining black lashes, those terrifying black lashes that inadvertently reveal some portion of a secretive gaze, allowing you to savor the image—smooth, olive cheeks veiled by wispy, black strands—for just a moment before the inevitable and immediate turning of the features which, in an unabashed abortion of your fleeting eye contact, now gaze blankly at some distant and insignificant object.

I had never really hated the color of MY skin. For the first time in my life, I had a reason to. And I did. Every white American needs to experience some situation where the color of their skin, their money, their last name, and the size of car they drive get them a grand total of jack and shit-no special treatment, no prompt service, no valet, no exact change, and, sorry, no complimentary mint upon their pillow. Maybe then we can start to imagine what it's like to be on the wrong side of hate.

Putting on that mask did for me what all the drinking of local wines, frail attempts at learning the language, cheering at soccer games, wearing of slick euro-style shirts, and other acquired behaviors could not. For at least one moment, I was passing for a Greek, moving on equal footing with the masses around me, part of a single, pulsating organism of masked faces and sweating bodies. I'm not making this shit up. I was there.

If you get the opportunity to live in someone else's country, consider yourself lucky. And if you get the opportunity to stay there for five months, again, consider yourself lucky.

And if in those five months you manage to transcend for just a moment all those things that had kept you from seeing through the eyes of a native, consider yourself supremely lucky. Kay and I fooled a country full of people; for just a moment, we were something other than ourselves. Excerpted from Cigarettes, Please: a journal of transition, completed for Professor Joy Castro's Narrative Theory and Contemporary Memoir course. Photo by Reiters/CORBIS

|