|

July 12, 2004

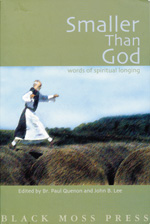

| | The cover shot on Smaller Than God pictures Brother Paul in a field in his monk’s garb—habit and robe—leaping across freshly rolled hay.

| | State Road 247 lies just west of the walls of Gethsemani monastery in Trappist, Kentucky. It runs south, eventually to Maker’s Mark Bourbon Distillery, and north through historic Bardstown, where the big trade used to come, and up then to Louisville. Two trails run out into the west end of the monks’ 2,500 acres of earth and sky. It is summer afternoon. We are finishing a long hike on the southern trail. I wander off to spy out an abandoned building. The monk says nothing. I turn around. Did "Go for a walk," mean "Stay on the trail"? Looking at his face, I see cool vigor in two black eyes. I see something beyond peace. I see sharp obsidian, like black ice in the dull heat. I don’t turn around again. Brother Paul recently finished co-editing a book of spiritual poetry titled Smaller Than God. The cover shot pictures him in a field in his monk’s garb—habit and robe—leaping across freshly rolled hay. The humpbacks of the bales roll up and down like Kentucky knobs; and Paul crosses them, as he’s crossed all the knobs from New Haven to Elizabethtown, from Bardstown to Hodgenville, like a dancer: foot pointed, hand up, balanced bearing, full stride, full stretch, posture, poise, form, but not stifled by technique—gracefully spontaneous—carried away by the inertia of linear jumping and getting faster as he goes. The photo freezes him, mid-jump, aloof, lofty on the heights of Gregorian contemplation, ready to levitate off the cover. I imagine his foot touching the bales only for a moment, making a soft crunch—not autumn leaf, but a silky crunch, a sweet, earthy sound like the sound of good freedom. He plays like a child dressed for church—aware of his robes, but fearlessly creative. Abbot Damien and Brother Thomas tell me to stay away from Paul, that he is not a good example for a young man learning how to retreat from the world. But the monks gossip more than schoolgirls. Besides, Paul exudes good poetry. He is good poetry, living what poets write about, hiking hours in the crystal night, swimming naked in Basil’s Lake till November, dancing in the woods, and sleeping under a wood shed all year long. The barn we’ve approached is different from the traditional Indiana barns I know. It’s an old cow milking barn. The single story is made of cinder blocks and topped by a tarpaper roof shaped like the inverted hull of Noah’s ark. From 247 it looks like a giant hay bale. The centers of the foggy glass blocks are busted out from rock games. The old fences for the cows are dismembered and the concrete driveway is earthquaked by ugly yellow grass. We walk on the crunch and pop of broken glass, cuts of black roof and tiny pebbles. The black barn doors are warped and rusted on their tracks; one is blown open. Hay waits at the entrance. A dozen hay bales are sagging together in a circle like they tried to get warm all winter. They’ve turned from verdant green to gold to gray. Old hay. The air is warm and flies buzz. The light is dull. In the thickness of the air the smell of hay lingers, but it’s not rich and pungent like the presence of warm animals. Immediately I enter and clench the strings of a giant bale. I am up. I crouch. Take off. Crash. Thump! Head thrown back. Knees collapse. Then grasp the hay, the strings; and bits fly. I repeat, throwing my body out again. But the hay won’t give; the bales wobble and teeter as I land with a deep thump. It’s like jumping on fat balloons weighted with sand. I want to jump high, I want to jump far, want to jump wild. But the ceiling is low. Rusty stabilization bars cross above the bales, and roof nails peek ominously. There are swallows’ nests of clay and fishing line, bees’ umbrella hives, and clay tubes of the mud dauber wasp built in the joints of the x-truss roof. I don’t see any of it, but feel it the way I feel the itchy straw in my shoes as I jump hunched over into the bales. I’d like to feel poetic now. I’d like to feel just smaller than God. I’d like to be inspired by my muse of hay. I want to feel this thrashing and threshing is poetry. Is this it? Then Paul climbs up, looking like a ferret with his white beard. He takes a wide-armed hop. He explores by testing the boundaries of situations, not banging his head against them or trampling them. Imagination seizes him and only the jumping is there, like the monks leaning against the choir stalls before prayer, their arms crossed inside their cowls, as they lean back with closed eyes and the shower of dust motes fall quiet in the afternoon light. I watch him with the fear of being left in reality. I want to do extreme hay jumping. I can’t be balance-monk, smooth-monk, linear-leaping-monk. I want to spread myself as thin as possible. I want to write Indian-blood poems that swing from the rafters. This is my struggle with the muse of hay—poetry for the novice—learning to jump soul first. I climb back up, leap over a chasm in the center of the hay, and fall directly in the dips between bales. Then I slide off the edge. I climb back up again and let my knees buckle me into collapse. I look absurd. My fingers grab at the hay. Where is it? Where is the monk? I am decked from behind. When I realize what has happened I am wedged like an ax in the dark of the bales. Hay is in my hair; my foot’s in the air and he looms like King of the Mountain with a large, white grin. I look up at Paul, and we laugh together. Contact Dits at ditsa@wabash.edu

|