Magazine

![]()

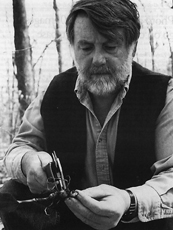

'Til Hill and Valley are Ringing

|

State and federal officials knew something had to be done and have been passing legislation to protect the bay and funding projects to search for cures for its declining health. The work of Dennis Whigham '66, research ecologist for the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, is one of the many tonics they'll likely use to bring back the bay.

Whigham and his colleagues have been studying the ways natural wetlands can filter out the pollution that seeps into bay from farm fields and suburban lawns (pollution referred to as "non-point source pollution, or, as Dennis calls it, "any pollution that doesn't come out of a pipe"). Whigham's project involves land on the eastern shore of the bay that was originally wetlands but was later converted to agricultural use. The scientists have restored this area to wetland habitat and have allowed the surrounding fields to drain through them.

"We then measure to determine how well the wetlands do at intercepting materials before they get into the streams or directly into the bay," the former Wabash biology major explains. The wetlands are doing their job well.

"We're into the third year of the project now and from continuous monitoring at a couple of stations we're finding that, in both very wet and very dry years, the wetlands do a good job of removing nitrogen and phosphorus," Whigham says. "Particularly in your average to dry year, they do even better than the stated goals for reducing non-point sources of pollution."

"If the positive results continue to roll in, more wetlands will likely be restored on the eastern shore of the bay," explains the ecologist, who has spent the past 20 years working on a variety of projects for the Smithsonian.

Another of Whigham's favorite projects is a groundbreaking study of terrestrial orchids that grow wild in the forests of the Eastern U.S.

"There's almost nothing known about the early life history stages of these plants because they are so small you can hardly see them," Whigham says. He and a colleague in Denmark are working to develop new techniques to work with the seeds of the tiny plants.

"We're opening up a whole new world, studying not only the orchids, but the fungi that they need as well. We're finding that the orchids and the fungi they need have an interaction with decomposing wood in the forest, so that gets to the issue of how you manage these forests and why you need to leave fallen wood on the ground there.

"People have addressed that question before, but this adds another dimension to it," Whigham says. "There may be some species of plants that live in the forest understory that simply can't make it unless they have access to decomposing wood and the fungi that are supported by it."